Arthritis

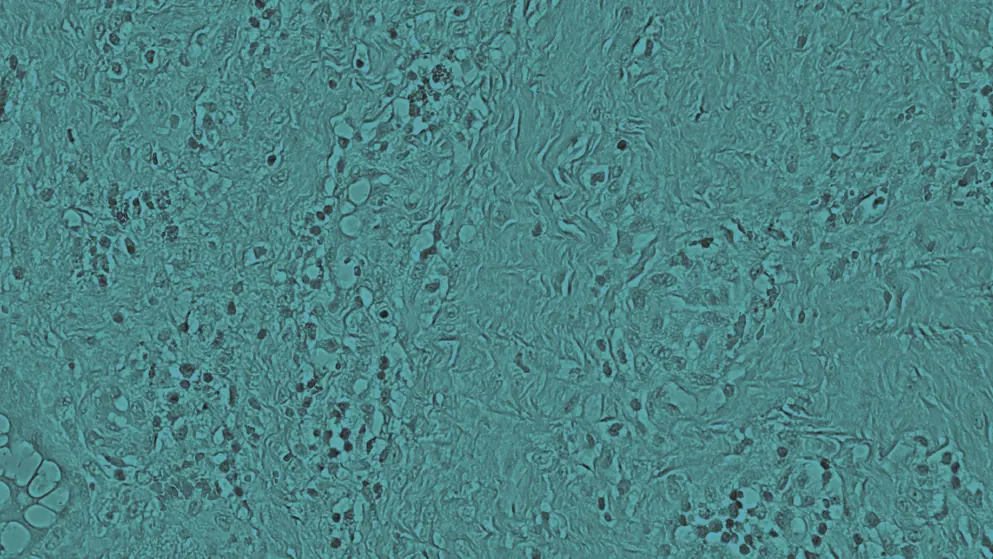

Arthritis refers to a group of conditions that cause inflammation in one or more joints, which may be acute or chronic. The most common forms include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout. Examples of less common types of arthritis include septic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and reactive arthritis. It is estimated that more than 350 million people have arthritis globally.

Who is most commonly affected?

Osteoarthritis is the leading type of arthritis among adults. It typically develops after the age of 50 but can occur earlier, and becomes increasingly common with advancing age. Other risk factors for arthritis include family history, female sex, previous joint injuries, and obesity.

What symptoms are linked to arthritis?

Symptoms can differ depending on the type of arthritis. Common symptoms include pain, stiffness, joint inflammation, restricted joint movement, warmth and redness around the affected joint, weakness, and muscle wasting.

How does arthritis impact quality of life?

Living with arthritis can make even the simplest everyday tasks challenging. People with arthritis may require assistance with personal care, getting dressed, meal preparation, household duties, and work-related activities. Beyond the physical limitations, arthritis can have a psychological toll, with some people experiencing anxiety, depression, or emotional distress because of chronic pain and reduced independence.

What treatment options are available for arthritis?

The goal of arthritis treatment is to ease symptoms and enhance joint mobility. Management strategies are guided by the type of arthritis diagnosed. Medications used to treat arthritis include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), counterirritants, steroids, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Physical therapy may also be beneficial for some patients. When non-surgical treatments fail to provide relief, surgical intervention may be recommended.

Developed by EPG Health for Medthority, independently of any sponsor.

Browse older resources

Managing Osteoarthritis-Associated Pain Learning Zone

Did you know that treating pain in osteoarthritis (OA) is changing? Discover the burden of OA, emerging therapies and personalised pain management.

Optimising Anti-TNF Treatment Using Biosimilars

Biosimilars are uniquely placed to change clinical practice in the fields of gastroenterology, rheumatology, and dermatology. The adoption of biosimilars can improve patient access to the most appropriate treatment, at the optimum time, to ensure the best possible long-term disease outcomes.