HS overview

HS epidemiology

Estimates of the prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) vary widely and are determined by the method of data collection1. Currently, assessments of three main types of studies are used to produce estimates of prevalence and give important insights into the populations impacted by this disease: self-reporting, registry-based, and group examination studies1.

What is the global prevalence of HS?

In recent years, a range of studies have estimated the global prevalence of HS as being between 0.00033–4.1%, and more recent studies in the United States and Europe have potentially narrowed this range to 0.7–1.2%2–15.

However, in a systematic review and meta-analysis (N=118,760,093) of HS cases, differences in prevalence were found when stratifying by geographic region (Figure 1)16. The highest prevalence was seen in Europe, 0.8% (0.5–1.3%), followed by the USA, 0.2% (0.1–0.4%), Asia-Pacific, 0.2% (0.01–2.2%), and South America, 0.2% (0.01–0.9%)16.

Figure 1. Forest plot of pooled hidradenitis suppurativa prevalence, stratified by geographic region (Adapted16).

One study included in the systematic review and meta-analysis was a population-based observational and case–control study of hospital episode statistics from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) by Ingram et al.5.

In this study, it was found that around 30% of people with HS were previously unrecognised and 18,417 cases had a history of 1–4 flexural skin boils, potentially giving rise to a higher prevalence of 1.19%5.

HS is often underdiagnosed and has a worldwide mean diagnostic delay of approximately 7–10 years17,18

Does HS prevalence differ by demographic?

HS appears to exhibit similar clinical features and endocrine comorbidities in both paediatric patients and adults19,20. However, HS is most highly prevalent between the third and fourth decades of life2–4,21–23. Moreover, HS appears to be very rare in women before menarche, although paediatric cases have been described24.

In the study by Ingram et al. 5, it was noted that the peak HS prevalence of 15.1 per 1,000 occurred in the fifth decade of life (Figure 2). The mean female-to-male ratio was 2.9:1 across the age groups5.

Figure 2. Prevalence of physician-diagnosed hidradenitis suppurativa cases by gender (Adapted5).

However, while studies have shown an increased prevalence of HS in women in European and North American populations6,7,21,22, studies in Asia have predominantly described cases of HS in men2,5,25–27.

In addition to gender, the Calao et al. study found statistically significant differences in age (P<0.0001), body mass index (P=0.0307), smoking status (P<0.0001), employment status (P<0.0001), and income (P=0.0321)2.

Race-specific differences in prevalence are difficult to define because of the limited reporting of ethnicity in HS studies28,29. However, African Americans are more likely to have clinic visits for HS than White Americans in the United States (OR, 2.00; P=0.047)30 and may be more affected by HS overall30-34.

HS symptoms

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa, is a chronic, inflammatory disorder of the skin that is defined by the nature and localisation of the skin alterations35. An understanding of the symptoms can both aid diagnosis and promote recognition of the immense burden of this disease.

Dr Joslyn Kirby describes how HS develops from early to late stages as well as the importance of engaging patients.

What are the symptoms of HS?

People with HS develop painful and inflamed nodules, abscesses and pus-discharging tunnels (known as sinus tracts and fistulas) between skin folds of the armpits, groin, gluteal, and perianal areas of the body (Figure 3)36.

Figure 3. Common skin on skin locations in which hidradenitis suppurativa can develop (Adapted37).

The most impactful symptom reported by most people with HS is chronic pain, which ranges from mild to severe in intensity18,38. Usually resulting from the inflammatory nodules or abscesses associated with the disease, pain is reported by 97% of patients during their disease course38. HS causes both nociceptive pain (resulting from tissue injury and inflammation) and neuropathic pain (likely arising from chronic inflammation and somatosensory nervous system dysfunction)39. Acute pain is predominantly nociceptive, while chronic pain can be categorised as nociceptive or neuropathic39.

The pain associated with HS may be of a higher intensity than other dermatological conditions40–42Patients describe the pain as hot, burning, pressing, stretching, cutting, sharp, taut, splitting, gnawing, sore, throbbing, or aching38,40.

The physical manifestations of HS, including severe pain and purulent secretions that restrict movement and produce an unpleasant smell, have a profound impact on the lives of patients43.

Pruritus is also a frequently mentioned symptom43, which has been shown in two previous studies to have a prevalence of 41.2–67.6%38,44. Although no specific correlation was found between pruritus intensity and disease severity, the intensity of the pruritus was associated with a negative impact on quality of life38,44.

How do the symptoms of HS progress?

When HS begins to develop, it usually progresses through the following stages37:

- Area of skin feels uncomfortable

- Tender, deep nodules appear

- Nodules grow and start to join together

- Large, painful, abscesses break open

- Blackhead-like spots appear

- Abscesses heal slowly (if at all) and return; tunnels (or sinus tracts) and scars form

Comparatively little is known about the long-term evolution of HS. Some studies using self-reported real-world data have shown that approximately one-third of patients achieve remission, while one-third remain unchanged or worsen45. One-third achieve amelioration, possibly because of improved coping over time45.

What are the comorbidities of HS?

Outside of the physical burden of HS, a broad range of comorbidities have been observed in patients, including:

- Inflammatory skin conditions (acne, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, pilonidal disease, and pyoderma gangrenosum)46

- Inflammatory diseases (inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthritis)46

- Lymphomas47

- Down syndrome46

- Cardiovascular (including hypertension and major adverse cardiac events) and metabolic diseases (including obesity, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome)46

- Pain disorders (fibromyalgia, migraines)48

- Chronic fatigue syndrome48 and sleep disorders49

- Sexual dysfunction46

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome46

- Mood (including depression, anxiety, and suicidality) and substance use disorders (including alcohol, tobacco, and opioids46

Most notably, a study of 5,964 people with HS found an association with substantially increased mortality (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.35; 95% CI, 1.15–1.59), especially due to cardiovascular events (IRR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.42–2.67)50.

HS burden of disease

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has a substantially negative impact on quality of life that can persist for years due to an immense physical and psychological burden, including painful lesions, stigmatisation, and an increased risk of suicide43,51,52.

Dr Joslyn Kirby describes the impact and psychological burden of HS.

How does HS impact quality of life?

According to studies of quality-of-life impairment, people with HS have greatly reduced physical and mental health and commonly experience social challenges as a result of their symptoms (Figure 4)41,53,54.

Figure 4. Impact of hidradenitis suppurativa on patient quality of life as measured by the Short Form 36 items survey, with scores representing the percentage of the total possible score achieved (Adapted)43.

Using Short Form 36 items survey (SF-36) general health questionnaire scores, these studies have found that the domains with notably lower scores were role physical, bodily pain, general health, perception, social functioning, and role emotional, compared with the general population41,53.

Patients have reported negative impacts on their sex life54 as well as their professional lives, which can negatively affect their economic situation55,56In more severe disease (Hurley stage 3), physical functioning, vitality, and mental health were also found to be significantly deteriorated53.

Furthermore, HS can have a considerable impact on employment and finances54,55. In an observational, international, multicentre registry study (adult respondents, N=529), 40% of adults with HS reported being unemployed57. Of the adults who were employed, 64% had experienced a degree of work impairment attributed to their HS.57 Results from a Danish cross-sectional study (N=100) mirror these findings: 60.4% of employed respondents living with HS (n=57) reported a reduction in their work productivity as a result of HS symptoms, and the overall work productivity was reduced by 26.6%58. Risk of low income due to repeated sick leave or dismissal from the workplace has also been highlighted in an interview-based qualitative study (N=12)54.

What are the psychological and psychiatric burdens of HS?

Low self-esteem, loneliness, and fear of stigma

People with HS have significantly lower levels of self-esteem as well as higher levels of loneliness and social isolation52. Moreover, the emotional impact of HS increases the feeling of needing to isolate, due to the fear of stigmatisation54.

Risk of psychiatric comorbidities

People with dermatoses are generally considered to be at higher risk of psychiatric disorders than the overall population59,60. However, people with HS are thought to be particularly at risk given the impact on quality of life caused by their symptoms and associated comorbidities59.

In a Finnish nationwide registry study (N=4,381) aiming to clarify the association between HS and its psychiatric comorbidities, people with HS were compared with people with psoriasis and with melanocytic naevi, given the elevated risk of psychological comorbidities associated with these conditions59.

The total prevalence of psychotic disorders was 4.7% in the HS group, compared with 3.3% in the psoriasis group (OR, 1.46; 95% CI; 1.24–1.72), and 1.7% in the melanocytic naevi group (OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 2.29–3.28)59.

Depression

In the same study, major depressive disorder was the most common psychiatric comorbidity across all groups; however, it occurred more frequently in people with HS than in those with psoriasis (15.3% vs 12.1%; OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.19–1.44) or melanocytic naevi (8.3%; OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.81–2.22)59.

Similar results were observed in a Danish registry study (N=7,732), showing a significant association between HS and depression (OR, 1.9), anxiety (OR, 2.34), and hospitalisations and usage of antidepressants or anxiolytics (OR, 2.02–2.65)51. The study found that the prevalences of depression (1.6%) and anxiety (0.8%) were higher than in the background population51.

The increased risk of depression associated with HS may even go beyond the burdens associated with the disease itself. It has been suggested that the overexpression of inflammatory markers in HS may play a role in the development of depression61-64.

Suicide

The Danish registry study also showed a strong association between HS and the risk of suicide (HR, 2.42), even following adjustment for age, sex, socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol misuse, and healthcare consumption51. Similarly, there was a significant association between HS diagnosis and suicide in a systematic literature and meta-analysis (from 82,276 patients with HS compared with 114,544,438 controls)16.

Considering the significant psychological burden of HS compared with the general population16 and other dermatoses,51,59 screening patients with HS for these comorbidities, as well as psychiatric referral and adequately managing pain, are critical steps to improve the overall wellbeing of patients16.

HS pathophysiology

The current understanding of the pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is limited35. The underlying pathological mechanisms of HS appear to be complex and multifaceted, simultaneously involving neutrophilic dermatosis, a strong anti-inflammatory component, and the potential involvement of B cells, TH1 cells, and TH17 cells35.

Dr Joslyn Kirby provides an overview of the complex pathophysiological mechanisms of HS.

What are the causes and risk factors of HS?

Dr Joslyn Kirby describes the factors that can influence the risk of developing HS, including genetics and lifestyle.

While the pathophysiology of HS is complex, it is strongly influenced by lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity; physical triggers such as friction and increased temperature; and changes in the skin microbiome65,66.

HS is also suspected to have a genetic predisposition, with studies showing heritability of up to 80%65,67. However, no causative genes have yet been conclusively identified. On the basis of current genetic knowledge, the disease can be categorised as familial, sporadic, syndromic, or ‘HS plus’, which occurs in association with other conditions such as Dowling–Degos disease and familial Mediterranean fever65,67. There is a high level of heterogeneity between these forms of HS; however, there may be an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance of familial HS68.

Research is ongoing to further elucidate the genetics related to HS. Genome-wide association studies and advanced molecular genetic techniques may reveal causative genes and loci, which may enable personalised management approaches65,68.

How does HS develop?

Beginning at the hair follicle, the earliest histologically detectable events in HS include35:

- Perivascular and perifollicular immune cell infiltration

- Hyperkeratosis

- Hyperplasia of the infundibular epithelium (infundibular acanthosis)

These alterations of the infundibular epithelium induce follicular occlusion, or ‘plugging’, followed by a stasis of follicular content, anaerobic bacterial proliferation, and hair follicle dilatation (Figure 5)35.

As follicular cells become damaged, bacterial components and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released, which may further stimulate inflammatory responses. It has been suggested that local macrophages may become activated, leading to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) (Figure 5)35.

Figure 5. Initial events involved in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa (Adapted35). AP-1, activator protein 1; CCL, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CXCL, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; IL, interleukin; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NLRP3, NACHT, LRR and PYD domain-containing protein 3; TH, T helper; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Bacterial sensing may also be strengthened through the increased expression of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) by local macrophages or dendritic cells35. Compared with healthy skin, the microbiome of the skin in HS is altered, with an increase in certain bacterial taxa, including anaerobes, and an overall decrease in microbial diversity66. These changes may contribute to the pathogenesis of HS via triggering immune system reactivity and inflammation66.

Once secreted, IL-1β and TNF act on various cell types with partially overlapping effects (Figure 5). IL-1β induces the production of chemokines, with the most prominent chemokines attracting neutrophilic granulocytes. TNF activates endothelial cells, causing a stronger expression of adhesion molecules, and stimulates an assortment of chemokines that attract neutrophils, T cell subsets, and monocytes into the skin35.

The importance of TNF involvement in the initial pathogenic events of HS is highlighted by patient responses to anti-TNF therapy35

The induction of chemokines and endothelial cell activation leads to an intense infiltration of immune cells into the developing lesions followed by the development of monocytes into macrophages and dendritic cells35.

While their precise role in the pathogenesis of HS has yet to be elucidated, various other cells are also seen to be prevalent in HS lesions, including35:

- Mast cells

- Natural killer cells

- B cells

- Plasma cells

Notably, HS differs from other immune-mediated skin disorders, such as psoriasis, due to the strong expression of the anti-inflammatory mediator IL-1035.

In people with HS who also smoke tobacco, nicotine can increase intracellular cAMP levels, possibly enhancing cutaneous IL-10 production35

Following induction by pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL-10 in macrophages can inhibit immune responses by suppressing monocyte and macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine production. This leads, both directly and indirectly, to a reduced T-cell activation35.

When does HS progress?

The sequential progression of HS is still poorly understood. However, the events seen in advanced disease can be distinguished from the initial pathogenic events (Figure 6)35.

Figure 6. The progression of hidradenitis suppurativa to advanced disease (Adapted35). AMP, antimicrobial protein; CL, chemokine ligand; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IFNγ, interferon-γ; IL, interleukin; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; TH, T helper; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

As HS progresses, a diverse range of immune cells permeate the skin and secrete specific cytokines35

T cells produce high levels of interferon-γ (IFNγ) and IL-17 in the skin of people with HS, similar to the levels in people with psoriasis. In a previous study, CD4+ T-cell enrichment was shown to secrete IFNγ and IL-17 in ex vivo experiments, implying that T helper (TH) cells can produce these mediators34.

IL-12 and IL-23 are present within the skin of people with HS. These cytokines support the function of TH1 and TH17 cells and can be produced by dendritic cells or macrophages34.

IFNγ activates macrophages and tissue cells, which may be essential for local T-cell activation34

In the HS lesions, the infiltration of immune cells from blood vessels is triggered by the activation of dermal endothelial cells by IFNγ. A positive feedback loop then forms, with IFNγ inducing the secretion chemokines, such as CXCL10, that attract TH1 cells (Figure 6)35.

Secreted predominantly by TH17 cells, IL-17 then works synergistically with other tissue-active cytokines, such as TNF, IL-22, and IFNγ, to stimulate the production of specific35:

- Chemokines, such as CCL20, CXCL1, and CXCL8

- Cytokines, such as G-CSF and IL-19

- Epidermal antimicrobial proteins (AMPs)

A reduced expression and action of IL-22 may play an important role in skin destruction and systemic metabolic changes seen in HS. Notably, IL-2235:

- Induces AMPs, especially in the presence of IL-17

- Helps protect tissue cells against cellular damage

- Counter-regulates inflammation-induced metabolic alterations

How do inflamed nodules or abscesses form?

Lowered AMP levels in the lesions result in a reduced ability to inhibit bacterial propagation35. This proliferation of intrafollicular bacteria, in addition to a massive infiltration of immune cells, leads to the rupturing of the dilated hair follicle. Inflammation then increases due to the release of follicular content into the tissue, such as DAMPs, keratin fragments, and bacterial products35.

TNF and IL-1β then induce chemokines that attract immune cells and activate endothelial cells, which allows immune cells to infiltrate the skin. This leads to the formation of subcutaneous inflammatory nodules and dermal abscesses35.

IL-1β induces the production of35:

- Cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-32

- Extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)

MMPs facilitate the rupture of adjacent dilated hair follicles and stimulate the destruction of the skin with the formation of physically burdensome abscesses and tunnels35.

IL-36 cytokines are also highly expressed in the lesions, promoting35:

- Neutrophil-attracting chemokines

- AMPs

- Specific cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-36γ

At the lesion, neutrophils then contribute to the production of inflammatory cytokines and pus formation35.

The neutrophils in HS have an enhanced ability to form neutrophilic extracellular traps (NETs) and the degradation of these NETs is impaired69. This is thought to contribute to inflammation and the generation of autoantibodies against DNA, nuclear proteins, and NET components, which further trigger aberrant immune responses69.

Neutrophils also produce lipocalin 2 and cathelicidin-derived peptide LL37. Lipocalin 2 is a cytokine that induces inflammatory pain and further neutrophil tissue infiltration, forming a positive feedback loop. Cathelicidin-derived peptide LL37 is an antimicrobial peptide that may play a part in T-cell proliferation within the lesions35.

As the tissue disintegrates, pus and follicular stem cells may promote the development of pus-draining epithelialised sinus tracts and fistulas. HS lesions also contain thickened interfollicular epidermis, in addition to inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and tunnels35.

The culmination of these activated immunological pathways leads to a lessened antimicrobial defence, the degradation of extracellular matrix, pus formation, and pyogenic progressive tissue destruction35.

HS diagnosis

Appropriate early identification and treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is essential for minimising the risk of disease progression and the development of associated comorbidities17.

However, as emerging HS lesions appear similar to other disorders, such as abscesses or boils, the disease is often underdiagnosed and has led to a worldwide mean diagnostic delay of approximately 7–10 years17,18.

How do you diagnose HS?

HS diagnosis is based on the nature and location of skin lesions as well as the disease course, which can be defined as persistent (lesions present for at least 6 months) or recurrent (>2 skin lesions occurring or recurring within 6 months)36,70.

Large international studies have shown that there is an average delay of 7–10 years between the onset of disease and the diagnosis17,18

Typical HS skins lesions are characterised by purulence, malodorous discharge, pain, and discomfort during daily life activities36.

Patients may present with one or multiple types of lesions simultaneously, which typically include70:

• Inflammatory nodules

• Abscesses

• Inflamed and draining sinus tracts or fistulas

• Rope-like scarring

• Open comedones

• Bridged scars

• Post-inflammatory double-ended pseudocomedones (resembling a ‘tombstone’)

Lesions generally appear in intertriginous areas or other areas such as the nape of the neck, the axillae, inguinal folds, buttocks, inframammary, or the retroauricular area. However, the location of these lesions in specific areas of the body is influenced by biological sex (Table 1)15,71,72.

Table 1. Differences in hidradenitis suppurativa lesion prevalence between men and women (Adapted15,71,72).

| Lesions with higher prevalence in men | Lesions with higher prevalence in women |

| • Armpits • Perineal or perianal regions • Buttocks • Gluteal cleft |

• Groin, specifically upper inner thigh • Submammary regions • Inframammary regions |

A family history can also be used to support the diagnosis of HS accompanied by various additional clinical signs, including recurrent atypical lesions in intertriginous areas, such as folliculitis and open comedones; the presence or history of a pilonidal sinus; and typical lesions in atypical locations, such as the inner thigh or the waist71,73.

What diagnostics can be used for HS?

Ultrasonography is now considered part of standard of care in HS and is used to identify clinically undetectable lesions, characterise disease severity, as well as guide surgical treatment74. Ultrasound machines with upper ranges working on 15–33 MHz can accurately visualise deeper layers of the skin and differentiate between lesional and non-lesional areas, while machines with frequencies up to 70 MHz can detect early subclinical features of HS73. Early signs include hair follicle abnormalities and fluid collection75,76.

Colour Doppler ultrasonography is reported to detect subclinical features more accurately than standard ultrasonography and can illustrate the surrounding vasculature75.

More advanced imaging modalities that may be used to diagnose HS include:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Enables complete body examination, allows differential diagnosis of perianal lesions caused by Crohn’s disease and pilonidal cysts, and may be helpful in preoperative assessment of fistulation in the anogenital area74,77

- Positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT): Has been used to identify HS lesions while examining patients for malignancies74

- Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM): May be used to identify subclinical features of HS as it has exceptionally high resolution and sensitivity but it cannot detect deep cutaneous tissues74

In cases of HS that are uncertain, biopsies can be used to reject other potential disorders, such as pyoderma gangrenosum, squamous cell carcinoma, or lymphomas35. However, skin biopsies are not usually required for the diagnosis of HS35.

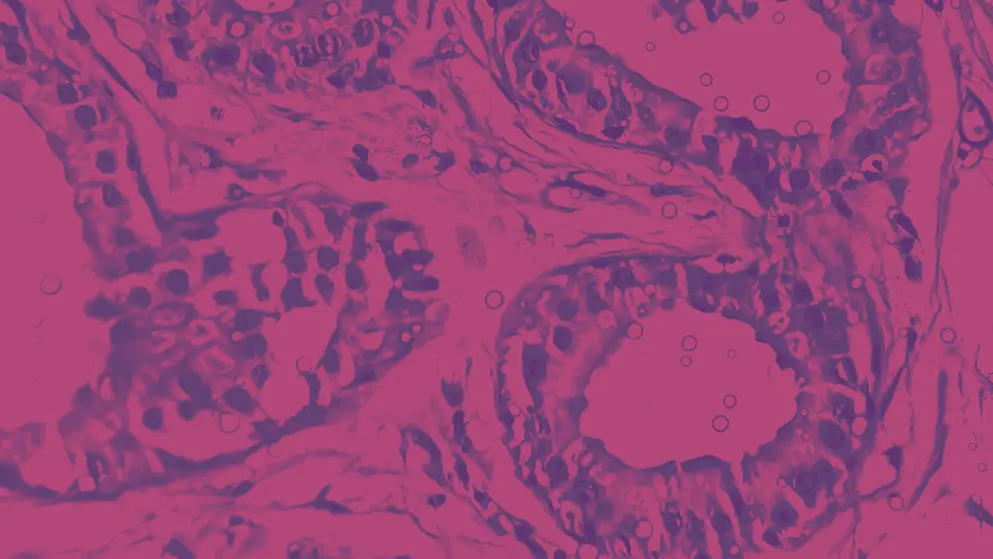

The type of alteration determines the histopathological characteristics of HS. These can range from early cysts, nodules, or abscesses to inflamed sinus tracts or rope-like scars78. In ruptured cysts, pan-keratin immunostaining as well as haematoxylin and eosin staining can be used to visualise the keratin fragments and debris that become dispersed in the dermis79.

There are alternative diagnostic techniques not typically used to diagnose HS that may prove useful in specific diagnostic scenarios:

- Bacterial cultures: Can be used in cases that are suggestive of infection rather than HS or secondary infection in HS35

- Dermoscopy: Polarised or incident light dermoscopy can be used to provide three-dimensional views of the skin surface and to identify clinical features of HS that may not be evident to the naked eye80

A plethora of biomarkers have been proposed as diagnostic indicators of HS, most notably serum interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R); however, these biomarkers remain to be clinically validated and so are not yet recommended for use in clinic35,81.

How do you classify severity in HS?

A complete body skin examination is necessary to assess the extent and severity of HS35. To classify the extent and severity, this examination can utilise a number of different scores (Table 2).

Table 2. Assessment scores and stages for hidradenitis suppurativa (Adapted35).

| *Score development based on 154 patients. †Score development and validation based on 236 patients. | |

| Severity or stage | Description |

| Hurley stage | |

| Stage I | Abscess formation, single or multiple, without sinus tracts or cicatrisation |

| Stage II | Recurrent abscesses, single or multiple, and widely separated lesions, with tunnel formation and/or scarring |

| Stage III | Diffuse or near-diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected tunnels and abscesses across the entire area |

| The Physician Global Assessment Tool for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS-PGA)* | |

| Clear | No abscesses, draining tunnels, inflammatory nodules or noninflammatory nodules |

| Minimal | No abscesses, draining tunnels or inflammatory nodules and the presence of noninflammatory nodules |

| Mild | No abscesses or draining tunnels and 1–4 inflammatory nodules, or 1 abscess or draining tunnel and no inflammatory nodules <10 inflammatory nodules |

| Moderate | No abscesses or draining tunnels and ≥5 inflammatory nodules, or 1 abscess or draining tunnel and ≥1 inflammatory nodule, or 2–5 abscesses or draining tunnels and <10 inflammatory nodules |

| Severe | 2–5 abscesses or draining tunnels and ≥10 inflammatory nodules |

| Very severe | >5 abscesses or draining tunnels |

| International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4)† |

|

| Mild | ≤3 points (number of inflammatory nodules ×1 and number of abscesses ×2) |

| Moderate | 4–10 points (number of inflammatory nodules ×1, number of abscesses ×2, and number of draining tunnels ×4) |

| Severe | ≥11 points (number of inflammatory nodules ×1, number of abscesses ×2, and number of draining tunnels ×4) |

Severity scores in HS

Severity scores in HS The earliest score to be introduced is the Hurley stage scoring system, a widely recognised and rapid classification of disease severity82. A more refined version also captures the extent of inflammation as well as distinction of severity within a single stage83.

Another tool frequently used in clinical trials and daily practice is the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) Tool84. As a rigid system that distinguishes only six stages, this tool is validated and easy to use, and also allows for the observation of changes during treatment84.

An alternative severity score is the Sartorius system, which provides a benefit over the Hurley stage score by detecting changes in severity over time as well as in response to treatment85. However, this score is labour intensive and is therefore not frequently used in clinical practice85.

A more recently developed tool for the classification of HS disease severity is the International HS Severity Score System (IHS4). This composite score is based on counts of inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and draining tunnels, which is then converted into one of three disease stages: mild, moderate, or severe86.

While useful as a baseline assessment to help make treatment decisions, this score lacks sufficient detail to provide precise descriptions of disease severity or therapy outcomes35. Scores based on lesion counts also fail to take into account extremely inflamed lesions containing indurated areas that lack clearly definable nodules, such as those found in Hurley stage 3 disease83,87,88.

Ultrasonography scorings

The sonographic staging of severity of HS (SOS-HS) represents a scoring that combines the findings of ultrasound assessment with clinically based Hurley staging to enable better staging of HS75. The SOS-HS considers the number of specific features of lesions, and patients are categorised into stage 1, 2 or 375.

Recently, a modified SOS-HS (mSOS-HS) has been proposed, which considers the number of affected regions, the number of key lesions such as pseudocysts, fluid collections, and tunnels76. The mSOS-HS includes four severity categories, stage 1, 2, 3a, and 3b, with stage 3b representing people with a very high number of tunnels that may need more urgent treatment76.

Another ultrasound-based scoring, the Ultrasound HS Activity Scoring (US-HSA), has also been proposed to assess disease severity and disease progression76. The US-HSA considers the corporal regions and subregions in standardised colour Doppler examinations at basal stage and follow-ups, and patients receive a variable score out of a maximum of 18 points76.

Patient-reported scores

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have also attracted attention. Commonly used PROMs include the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), and Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for pain and itch89-92.

Biomarkers

As visual assessments of severity do not reliably assess the extent of the disease into deeper skin regions, blood biomarkers have gained increasing interest as an objective assessment of disease activity.

Several proteins have already been identified as being increased in HS, such as chitinase-3-like protein 193, matrix metallopeptidase 8 (MMP8)94, lipocalin 295, IL-696,97, and C-reactive protein96, the expression of which correlate to the extent of inflammatory skin alterations.

Levels of serum amyloid A (SAA) were shown to be significantly associated with the number of nodules, abscesses, fistulas, and severe disease, and the study authors have recommended monitoring therapeutic response to prevent disease flares (new or substantial worsening of clinical signs and symptoms)98,99.

None of the identified biomarkers currently have sufficient clinical validity to be recommended for diagnosing or assessing severity of HS in clinical practice81.

References

- Jemec and Kimball, 2015. Hidradenitis suppurativa: Epidemiology and scope of the problem. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.052

- Calao, 2018. Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) prevalence, demographics and management pathways in Australia: A population-based cross-sectional study. https://www.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200683

- Cosmatos, 2013. Analysis of patient claims data to determine the prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2012.07.027

- Jemec, 1996. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90321-7

- Ingram, 2018. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16101

- Miller, 2016. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Comorbidities of Hidradenitis Suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2015.08.002

- Andersen and Davis, 2016. Prevalence of Skin and Skin-Related Diseases in the Rochester Epidemiology Project and a Comparison with Other Published Prevalence Studies. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000444580

- Sung and Kimball, 2013. Counterpoint: analysis of patient claims data to determine the prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.043

- Garg, 2017. Sex- and Age-Adjusted Population Analysis of Prevalence Estimates for Hidradenitis Suppurativa in the United States. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0201

- Ingvarsson, 2017. Regional variation of hidradenitis suppurativa in the Norwegian Patient Registry during a 5-year period may describe professional awareness of the disease, not changes in prevalence. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14990

- Theut Riis, 2019. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16998

- Ianhez, 2018. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in Brazil: a population survey. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/ijd.13937

- Delany, 2018. A cross-sectional epidemiological study of hidradenitis suppurativa in an Irish population (SHIP). https://www.doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14686

- Fania, 2017. Prevalence and incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa: an exercise on indirect estimation from psoriasis data. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14224

- Vazquez, 2013. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Phan, 2020. Global prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and geographical variation—systematic review and meta-analysis. https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s41702-019-0052-0

- Saunte, 2015. Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14038

- Garg, 2020. Evaluating patients' unmet needs in hidradenitis suppurativa: Results from the Global Survey Of Impact and Healthcare Needs (VOICE) Project. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1301

- Braunberger, 2018. Hidradenitis suppurativa in children: The Henry Ford experience. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/pde.13466

- Liy-Wong, 2015. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the pediatric population. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.051

- Fabbrocini, 2016. South Italy: A Privileged Perspective to Understand the Relationship between Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Overweight/Obesity. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000447716

- Katoulis, 2017. Descriptive Epidemiology of Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Greece: A Study of 152 Cases. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000475822

- Andrade, 2017. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiological study of cases diagnosed at a dermatological reference center in the city of Bauru, in the Brazilian southeast State of Sao Paulo, between 2005 and 2015. https://www.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175588

- Deckers, 2015. Correlation of early-onset hidradenitis suppurativa with stronger genetic susceptibility and more widespread involvement. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.11.017

- Kurokawa, 2015. Questionnaire surveillance of hidradenitis suppurativa in Japan. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.12881

- Sabat, 2012. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with acne inversa. https://www.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031810

- Yang, 2018. Demographic and clinical features of hidradenitis suppurativa in Korea. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14656

- Lee, 2017. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Disease Burden and Etiology in Skin of Color. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000486741

- Greif, 2024. Evaluating minority representation across health care settings in hidradenitis suppurativa and psoriasis. https://www.doi.org/10.1097/jw9.0000000000000129

- Udechukwu and Fleischer, 2017. Higher Risk of Care for Hidradenitis Suppurativa in African American and Non-Hispanic Patients in the United States. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2016.09.002

- Vlassova, 2015. Hidradenitis suppurativa disproportionately affects African Americans: a single-center retrospective analysis. https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2176

- Reeder, 2014. Ethnicity and hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.220

- Vaidya, 2017. Examining the race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa at a large academic center; results from a retrospective chart review. https://www.doi.org/10.5070/d3236035391

- Garg, 2017. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: A sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Sabat, 2020. Hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0149-1

- Saunte and Jemec, 2017. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.16691

- American Academy of Dermatology Association, 2022. Hidradenitis suppurativa: Signs and symptoms. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/a-z/hidradenitis-suppurativa-symptoms

- Matusiak, 2018. Clinical characteristics of pruritus and pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2815

- Savage, 2021. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- Smith, 2010. Painful hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181ceb80c

- Wolkenstein, 2007. Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: A study of 61 cases. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.061

- Onderdijk, 2013. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04468.x

- Matusiak, 2020. Profound consequences of hidradenitis suppurativa: a review. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16603

- Vossen, 2017. Assessing Pruritus in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Cross-Sectional Study. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s40257-017-0280-2

- Kromann, 2014. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: A cross-sectional study. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13090

- Garg, 2022. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: Evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Tannenbaum, 2019. Association Between Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Lymphoma. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5230

- Prens, 2022. New insights in hidradenitis suppurativa from a population-based Dutch cohort: prevalence, smoking behaviour, socioeconomic status and comorbidities. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20954

- Yeroushalmi, 2023. Hidradenitis suppurativa and sleep: a systematic review. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s00403-022-02460-x

- Egeberg, 2016. Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264

- Thorlacius, 2018. Increased Suicide Risk in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.008

- Kouris, 2017. Quality of Life and Psychosocial Implications in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000453355

- Alavi, 2015. Quality-of-Life Impairment in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Canadian Study. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s40257-014-0105-5

- Esmann and Jemec, 2011. Psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa: A qualitative study. https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1082

- Matusiak, 2010. Hidradenitis suppurativa markedly decreases quality of life and professional activity. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.021

- Theut Riis, 2017. A pilot study of unemployment in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in Denmark. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14922

- Kimball, 2020. Baseline patient-reported outcomes from UNITE: an observational, international, multicentre registry to evaluate hidradenitis suppurativa in clinical practice. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16132

- Yao, 2021. Effectiveness of clindamycin and rifampicin combination therapy in hidradenitis suppurativa: a 6‐month prospective study. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19578

- Huilaja, 2018. Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa Have a High Psychiatric Disease Burden: A Finnish Nationwide Registry Study. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.06.020

- Dalgard, 2015. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. https://www.doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.530

- Kurek, 2013. Depression is a frequent co-morbidity in patients with acne inversa. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/ddg.12067

- Matusiak, 2009. Increased serum tumour necrosis factor-α in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: Is there a basis for treatment with anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agents? https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-0749

- Raison, 2006. Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006

- Van Der Zee, 2011. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: A rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10254.x

- Pace, 2022. The Genomic Architecture of Hidradenitis Suppurativa-A Systematic Review. https://www.doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.861241

- Lelonek, 2023. Skin and Gut Microbiome in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11082277

- Balić, 2023. The genetic aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2023.08.022

- Moltrasio, 2022. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Perspective on Genetic Factors Involved in the Disease. https://www.doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10082039

- Oliveira, 2023. Neutralizing Anti‒DNase 1 and ‒DNase 1L3 Antibodies Impair Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Degradation in Hidradenitis Suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2022.06.024

- Freysz, 2015. A systematic review of terms used to describe hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13940

- Schrader, 2014. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study of 846 Dutch patients to identify factors associated with disease severity. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.001

- Revuz, 2009. Hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03356.x

- Boer, 2017. Should Hidradenitis Suppurativa Be Included in Dermatoses Showing Koebnerization? Is It Friction or Fiction? https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000472252

- Nazzaro, 2023. The role of imaging technologies in the diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2023.08.023

- Mendes-Bastos, 2023. The use of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa: a narrative review. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljad028

- Wortsman, 2024. Update on Ultrasound Diagnostic Criteria and New Ultrasound Severity and Activity Scorings of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Modified SOS-HS and US-HSA. https://www.doi.org/10.1002/jum.16351

- Virgilio, 2015. Utility of MRI in the diagnosis and post-treatment evaluation of anogenital hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000000379

- Jemec and Hansen, 1996. Histology of hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90277-7

- Van Der Zee, 2012. Alterations in leucocyte subsets and histomorphology in normal-appearing perilesional skin and early and chronic hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10643.x

- Lacarrubba, 2017. Double-ended Pseudocomedones in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Histopatho-logical Correlation. https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2601

- Der Sarkissian, 2022. Identification of Biomarkers and Critical Evaluation of Biomarker Validation in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4926

- Davidson, 1989. Dermatologic Surgery. https://www.doi.org/10.1288/00005537-198909000-00019

- Horváth, 2017. Hurley staging refined: A proposal by the Dutch Hidradenitis Suppurativa Expert Group. https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2513

- Kimball, 2012. Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe Hidradenitis suppurativa: a parallel randomized trial. https://www.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00004

- Sartorius, 2009. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

- Zouboulis, 2017. Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15748

- Kokolakis and Sabat, 2018. Distinguishing mild, moderate, and severe hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1599

- Hessam, 2018. A novel severity assessment scoring system for hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5890

- Chernyshov, 2019. The Evolution of Quality of Life Assessment and Use in Dermatology. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000496923

- Ferreira-Valente, 2011. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005

- Kimball, 2016. Psychometric properties of the Itch Numeric Rating Scale in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14464

- Pedersen, 2017. Reliability and validity of the Psoriasis Itch Visual Analog Scale in psoriasis vulgaris. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2016.1215405

- Matusiak, 2015. Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (YKL-40): Novel biomarker of hidradenitis suppurativa disease activity? https://www.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2061

- Tsaousi, 2016. MMP8 Is Increased in Lesions and Blood of Acne Inversa Patients: A Potential Link to Skin Destruction and Metabolic Alterations. https://www.doi.org/10.1155/2016/4097574

- Wolk, 2017. Lipocalin-2 is expressed by activated granulocytes and keratinocytes in affected skin and reflects disease activity in acne inversa/hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15424

- Jiménez-Gallo, 2017. The Clinical Significance of Increased Serum Proinflammatory Cytokines, C-Reactive Protein, and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1155/2017/2450401

- Witte-Händel, 2019. The IL-1 Pathway Is Hyperactive in Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Contributes to Skin Infiltration and Destruction. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.11.018

- Iannone, 2023. Serum Amyloid A: A Potential New Marker of Severity in Hidradenitis Suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000528658

- LeWitt, 2022. International consensus definition of disease flare in hidradenitis suppurativa. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21647

This content has been developed independently by Medthority who previously received educational funding from Novartis Pharma AG in order to help provide its healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.