Antiplatelet therapy in ACS

Antiplatelet therapy is a cornerstone of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) management. Discover:

- The currently available antiplatelet therapies for patients with ACS

- The challenges in antiplatelet therapy selection for ACS

- The ESC and ACC/AHA guideline recommendations in our infographics

Antiplatelet therapies in acute coronary syndrome

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is an umbrella term for conditions characterised by a sudden reduction or occlusion of blood supply to the heart. ACS presentations include unstable angina, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Unstable angina and NSTEMI are grouped together as NSTE-ACS. The most common symptom of ACS is chest pain or discomfort; however, signs and symptoms may vary significantly depending on age, sex and other medical conditions.

ACS is a common cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide (Figure 1)1.

Amongst cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), ACS is the most common cause of death and predictions suggest that the burden will increase globally2

The total number of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to ACS has risen steadily since 1990, reaching 182 million (95% uncertainty intervals [UI], 170 to 194 million) DALYs and 9.14 million (95% UI, 8.40 to 9.74 million) deaths in 20192. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019 estimated 197 million (95% UI, 178 to 220 million) prevalent cases of ACS in 20192.

Figure 1. Proportion of global cardiovascular disease deaths in 2019 by underlying causes (Adapted2).

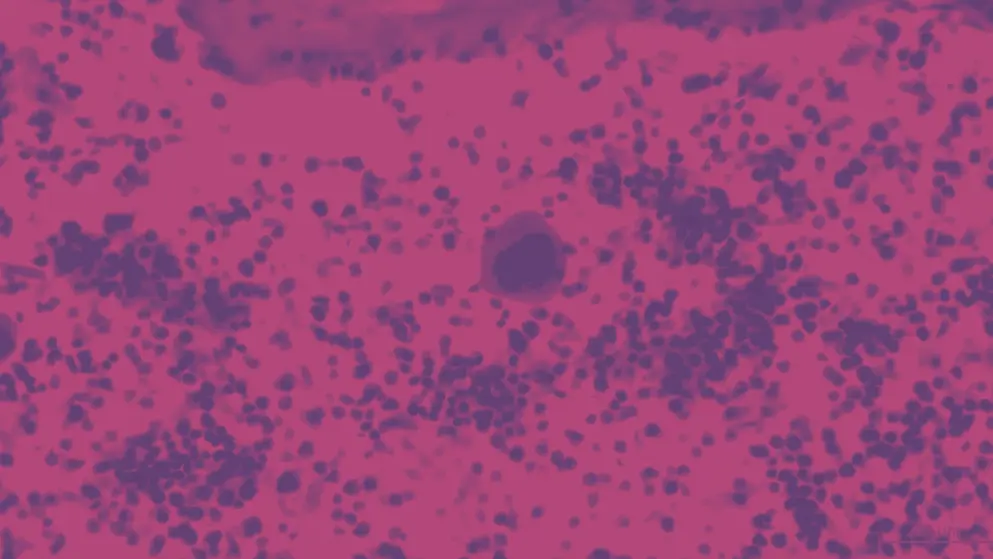

ACS results primarily from disruption of atherosclerotic plaques, which leads to thrombus formation and acute obstruction of coronary blood flow (Figure 2). Disruption of the atherosclerotic plaque can be caused by plaque rupture or plaque erosion. Both causes of disruption result in exposure of thrombogenic material within the plaque, including collagen and von Willebrand factor (vWF), which stimulate platelet adhesion3. The next step in the pathogenesis of ACS is platelet activation and release of vasoactive substances (thromboxane A2 (TXA2), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), serotonin, epinephrine, and thrombin), which promote interactions between adherent platelets, as well as further recruitment and activation of circulating platelets3. Binding of ADP to platelet P2Y12 receptors activates the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor (GPIIb-IIIa). Activated GPIIb/IIIa binds to the extracellular ligands, fibrinogen and vWF, leading to platelet aggregation and eventually to thrombus formation3.

Figure 2. Role of platelets in acute coronary syndrome pathophysiology (Adapted4). GPIIb-IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

Following immediate treatment of ACS to restore blood flow, long-term treatment aims to improve heart function and lower the risk of a heart attack, either through surgery or pharmacological management. Pharmacological treatment classes include antiplatelet therapies, thrombolytics, beta-blockers, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)5.

Antiplatelet therapy to prevent platelet activation and aggregation is essential in the management of ACS, particularly after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)5

Antiplatelet therapy options for ACS include aspirin, which binds to cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and inhibits TXA2 synthesis, and the P2Y12 inhibitors clopidogrel, ticagrelor, prasugrel and cangrelor5. These agents can be given as monotherapy or as dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) involving a combination of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor5. Other agents include the GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors eptifibatide and tirofiban and the protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1 inhibitor vorapaxar (Figure 3)5. Antiplatelet therapy is especially important after PCI because balloon angioplasty and stenting stretch the coronary arterial wall, leading to platelet activation, which induces inflammation and increases the risk of thrombosis6.

Figure 3. Therapeutic approaches for antiplatelet therapy (Adapted5).

Aspirin

Aspirin inhibits COX-1 in platelets, resulting in irreversible inhibition of the synthesis of TXA2, a potent vasoconstrictor and major inducer of platelet activation and aggregation7. The beneficial effects of low-dose aspirin in treating ACS have been well established since the 1980s8,9, and several randomised clinical trials have consistently demonstrated a dramatic reduction (40–50%) in the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction, stroke or vascular death among patients with ACS treated with aspirin10–14.

The question of the maintenance dose for aspirin has been long debated. Currently, maintenance doses range from 75–325 mg15. The only large-scale ACS randomised trial that compared lower dose (75–100 mg daily) with higher dose (300–325 mg daily) aspirin was the Clopidogrel Optimal Loading Dose Usage to Reduce Recurrent Events-Organisation to Assess Strategies in Ischemic Syndromes (CURRENT-OASIS 7) trial16. Here, 25,086 patients with ACS received either lower dose or higher dose aspirin, and there was no difference in death, myocardial infarction or stroke at 30 days (4.4% vs 4.2%, respectively)16. There was also no difference in overall bleeding events (2.3% for both aspirin doses) in the follow-up, although an increased rate of gastrointestinal bleeding in the higher dose group (0.2% vs 0.4%; P=0.04) was observed16.

P2Y12 inhibitors

P2Y12 inhibitors that are currently available include the orally active agents clopidogrel, ticagrelor, prasugrel and clopidogrel, and intravenously administered cangrelor (Figure 4)5.

Figure 4. P2Y12 receptor inhibition by different antiplatelet drugs (Adapted17). cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CYP, cytochrome P450; PKA, protein kinase A; VASP, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein.

Table 1 further summarises the differences and similarities between the drug characteristics for the P2Y12 inhibitors.

Table 1. Comparison of drug characteristics for P2Y12 inhibitors (Adapted18).

| Comparison of P2Y12 inhibitors | ||||

| Drug characteristic | Clopidogrel | Prasugrel | Ticagrelor | Cangrelor |

| Inhibition reversibility | Irreversible | Irreversible | Reversible | Reversible |

| Half-life | 6 h | 7 h | 7 h | 3–6 min |

| Onset of action | 4–8 h | 2–4 h | 2 h | Within 2 min |

| Offset of action | 5–10 days | 5–9 days | 5 days | 60 min |

| Method of administration | Oral | Oral | Oral | Intravenous |

| Dosing | Once daily | Once daily | Twice daily | Intravenous bolus and infusion |

Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel, an orally active, second-generation thienopyridine, inhibits ADP-induced platelet aggregation by inhibiting ADP binding to P2Y12 receptors and blocking the subsequent activation of the glycoprotein GPIIb/IIIa complex17. Clopidogrel is a prodrug that requires a two-step metabolism for biotransformation to its active form. The enzyme cytochrome P450 mediates oxidation of clopidogrel to 2-oxoclopidogrel, followed by conversion of 2-oxoclopidogrel to an active metabolite that irreversibly inhibits the P2Y12 receptor on the platelet surface19.

Clinical trials have shown that clopidogrel, an orally active irreversible P2Y12 inhibitor, significantly improves outcomes for patients with ACS without increasing fatal bleeding risk16,20,21

In the CURE (Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events) trial, patients with NSTEMI treated with 75–325 mg daily aspirin were randomised to receive clopidogrel (300 mg immediately, followed by 75 mg once daily; 6,259 patients) or placebo (6,303 patients)20. At 12 months, the primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke was significantly lower in the clopidogrel group than in the placebo group (9.3% vs 11.4%; P<0.001) with increased major bleeding (3.7% vs 2.7%; P=0.001), but no increase in fatal bleeding or intracranial haemorrhage20. A subgroup analysis involving 2,658 patients who received PCI (PCI-CURE trial) showed that clopidogrel was associated with significantly lower rates of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and urgent target-vessel revascularisation within 30 days of PCI, compared with placebo (4.5% vs 6.4%; relative risk [RR], 0.7; 95% confidence intervals [CI], 0.50–0.97; P=0.03)21.

The CURRENT–OASIS 7 trial investigated optimal clopidogrel and aspirin dosing16. In this study 25,086 patients with ACS were randomised to receive either the standard dose of clopidogrel (300 mg loading dose, then 75 mg daily) or double-dose clopidogrel (300 mg loading dose, 150 mg daily for 6 days, then 75 mg daily)16. Similar reductions in the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, stroke or myocardial infarction at 30 days were seen with double-dose and standard-dose clopidogrel (4.2% vs 4.4%, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 0.94; 95% CI, 0.83–1.06; P=0.30); however, double-dose clopidogrel was associated with higher rates of major bleeding (2.5% vs 2.0%; HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.05–1.46; P=0.01)16.

The main drawbacks associated with the use of clopidogrel are its slow onset of action and high interindividual variability in the response22. It is estimated that the percentage of nonresponders is around 25% and this nonresponsiveness is associated with a threefold increase in adverse outcomes23. Clopidogrel resistance is multifactorial24, but genetic polymorphisms in the metabolic activation of clopidogrel (e.g., cytochrome P450 2C19) and drug–drug interactions at this level (e.g., between proton pump inhibitors [PPIs] and clopidogrel) are both associated with decreased clopidogrel efficacy23. Therefore, it is important to consider clopidogrel resistance in some patients and establish strategies to manage this problem (e.g., genotyping, platelet aggregability tests, use of alternative antiplatelet drugs).

Prasugrel

Prasugrel is a third-generation, orally active thienopyridine that is more readily metabolised to its active metabolite, compared with clopidogrel24. This translates into a faster onset of action, lower interindividual variability of pharmacological response and, most importantly, greater antithrombotic efficacy25.

Prasugrel has a faster onset of action and greater antithrombotic efficacy than clopidogrel in patients aged <75 years or weighing >60 kg and with no history of stroke25,26

In the TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimising Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) study, 13,608 patients presenting with ACS, for whom PCI was planned, were randomised to receive either prasugrel (60 mg loading dose, then 10 mg daily maintenance dose) or clopidogrel (300 mg loading dose, then 75 mg daily maintenance dose) for a median of 14.5 months26. A significantly greater reduction in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke was seen in those treated with prasugrel, compared with clopidogrel (9.9% vs 12.1%; HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.73–0.90; P<0.001), primarily due to a reduction in myocardial infarction26. On the other hand, the greater mean inhibition of platelet function led to an increase in major bleeding in participants who received prasugrel (2.4% vs 1.8%; HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-–1.68; P=0.03)26. Specifically, a post hoc analysis of the TRITON-TIMI 38 study showed no net clinical benefit of prasugrel for patients aged 75 years or older (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.81–1.21; P=0.92) or weighing <60 kg (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.69–1.53; P=0.89) and net harm for those with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.02–2.32; P=0.04)26. When the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved prasugrel in July 2009, it prohibited prescribing it to patients with a history of stroke or TIA27–29.

Ticagrelor

Unlike clopidogrel and prasugrel, ticagrelor is not a thienopyridine. Ticagrelor is an orally active, direct-acting, third-generation reversible antagonist of the P2Y12 receptor30. It is associated with faster onset and a longer half-life than clopidogrel18,30.

Ticagrelor is an orally active, reversible P212 inhibitor with a faster onset of action, longer half-life and greater antithrombotic efficacy in ACS than clopidogrel18,30,31

The PLATO (Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial randomised 18,624 patients admitted for ACS to receive either ticagrelor (180 mg loading dose, then 90 mg twice daily) or clopidogrel (300–600 mg loading dose, then 75 mg daily)31. The primary composite outcome was cardiovascular mortality, stroke or myocardial infarction. At 12 months’ follow-up, ticagrelor was associated with a significantly greater reduction in the primary outcome, compared with clopidogrel (9.8% vs 11.7%; HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.77–0.92; P<0.001)31. Ticagrelor was also associated with significantly greater reductions in secondary endpoints, compared with clopidogrel, as well as a greater reduction in all-cause mortality (4.5% vs 5.9%; HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.69–0.89; P<0.001)31. No significant difference in the rates of major bleeding was found between the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups (11.6% and 11.2%, respectively; P=0.43), but ticagrelor was associated with a higher rate of major bleeding not related to coronary-artery bypass grafting (4.5% vs 3.8%; P=0.03)31.

The TWILIGHT study compared ticagrelor alone and in combination with aspirin in high-risk patients after coronary intervention32. Among high-risk patients who underwent PCI and completed 3 months of DAPT, ticagrelor monotherapy was associated with a lower incidence of clinically relevant bleeding than ticagrelor plus aspirin, with no higher risk of death, myocardial infarction or stroke32.

Cangrelor

Cangrelor is a direct, reversible, short-acting P2Y12 receptor inhibitor that has been evaluated during PCI for stable chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) and ACS in clinical trials comparing it with clopidogrel, administered before PCI [Cangrelor versus Standard Therapy to Achieve Optimal Management of Platelet Inhibition (CHAMPION PCI)] or after PCI (CHAMPION PLATFORM and CHAMPION PHOENIX)33–35. A meta-analysis of these trials showed a benefit with respect to major ischaemic endpoints that was counter-balanced by an increase in minor bleeding complications33. Moreover, the benefit of cangrelor with respect to ischaemic endpoints was attenuated in CHAMPION PCI with upfront administration of clopidogrel, while data for its use in conjunction with ticagrelor or prasugrel treatment are limited33. Given its proven efficacy in preventing intraprocedural and postprocedural stent thrombosis in P2Y12 receptor inhibitor-naive patients, cangrelor may be considered on a case-by-case basis in P2Y12 receptor inhibitor-naive patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI (NSTE-ACS) undergoing PCI36.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)

Although there are several potential combinations of antiplatelet therapy, the term and acronym DAPT has been used to refer specifically to the combination of aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor). DAPT provides greater platelet inhibition and has been shown to reduce recurrent major ischaemic events in patients with ACS5,30,37; however, DAPT also increases the risk of bleeding. There is general agreement that DAPT should be continued for 6–12 months after placement of a coronary stent38. The risks and benefits of extending DAPT treatment beyond six months have been investigated in several clinical trials38. Of these trials, the DAPT trial is the largest and the only double-blind trial to assess the risks and benefits of continuing DAPT for more than one year after placement of a drug-eluting stent39. This trial found that extending DAPT for 30 months significantly reduced the risks of stent thrombosis and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events but was associated with an increased risk of bleeding (Figure 5)39.

Figure 5. Results of the DAPT study on patients who had received drug-eluting stents (Adapted39). Cumulative incidence of stent thrombosis (left panel) and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (right panel). HR, hazard ratio.

The use of DAPT necessitates balancing the benefits of decreased ischaemic risk against the increased risk of bleeding38

Decisions about treatment with and duration of DAPT require a thoughtful assessment of the benefit/risk ratio, integration of study data and consideration of patient preference. For example, a longer duration of DAPT generally results in decreased ischaemic risk, compared with a shorter duration of DAPT, at the expense of increased bleeding risk40. The use of more potent P2Y12 inhibitors (ticagrelor or prasugrel) in place of clopidogrel also results in decreased ischaemic risk and increased bleeding risk40. In general, shorter duration DAPT can be considered for patients at lower ischaemic risk with high bleeding risk, whereas longer duration DAPT may be reasonable for patients at higher ischaemic risk with lower bleeding risk15.

Factors that increase ischaemic risk and may favour longer duration DAPT are38:

- Advanced age

- ACS presentation

- Multiple prior MIs

- Extensive CAD

- Diabetes mellitus

- CKD

Similarly, factors that increase the risk of stent thrombosis and may favour longer duration DAPT are38:

- ACS presentation

- Diabetes mellitus

- Left ventricular ejection fraction <40%

- First-generation drug-eluting stent

- Stent undersizing

- Stent underdeployment

- Small stent diameter

- Greater stent length

- Bifurcation stents

- In-stent restenosis

Conversely, factors that increase bleeding risk and favour shorter-duration DAPT are38:

- History of prior bleeding

- Oral anticoagulant therapy

- Female sex

- Advanced age

- Low body weight

- Chronic kidney disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Anaemia

- Chronic steroid or NSAID therapy

Tools to assess the benefit/risk of extending the duration of DAPT include the DAPT study score and the Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score41,42. A high DAPT score ≥2 in patients who have received a 12-month course of DAPT without experiencing ischaemic or bleeding events favours prolongation to 30 months42. Conversely, a high PRECISE-DAPT score of ≥25 at the index event signifies a high risk of bleeding and a potential benefit from shortened DAPT duration43.

In the STOPDAPT-2 trial (Short and Optimal Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy-2), 1-month DAPT followed by clopidogrel monotherapy as compared with 12-month DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel substantially reduced major bleeding events without an increase in cardiovascular events44. Therefore, 1-month DAPT followed by clopidogrel monotherapy might be an option in patients with high bleeding risk, although more data are needed.

ESC and ACC guideline recommendations for antiplatelet therapy

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommendations for antiplatelet therapy are available in three separate documents:

- 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation45

- 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with acute coronary syndrome without persistent ST-segment elevation15

- Focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) guidelines46

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) have produced the following guidelines in collaboration with the American Heart Association (AHA):

- 2013 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction27

- 2014 ACC/AHA guideline for non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes28

- 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome38

The ACC and AHA have also produced the 2021 guideline for coronary artery revascularization47, which is an update of the 2011 and 2015 guidelines. The 2021 update also replaces some sections of the 2013 guideline for ST-elevation myocardial infarction27 (STEMI) and the 2014 guideline for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome28 (NSTE-ACS).

The ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines consider antiplatelet therapy a cornerstone in the treatment of patients with ACS48. However, it is important to highlight the need to tailor treatments according to thrombosis risk versus bleeding risk (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Determinants of antithrombotic treatment in acute coronary syndrome (Adapted15). ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CCS chronic coronary syndrome; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; NSTE-ACS, non-ST segment elevation-acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Current guidelines recommend that all patients with ACS, whether STEMI or NSTE-ACS, should start aspirin therapy, unless there are contraindications such as risk of life-threatening bleeding or hypersensitivity15

ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines differ slightly in the dose of aspirin recommended (150–300 mg or 162–325 mg, respectively)15,27,28. A second antithrombotic agent should also be considered for extended long-term secondary prevention in patients with a high risk of ischaemic events and without increased risk of major or life-threatening bleeding (Class IIa recommendation)27,45.

Recommendations for the use of P2Y12 inhibitors in ACS

There is limited evidence for the optimal timing of initiating antiplatelet therapy with P2Y12 inhibitors in patients presenting with ACS. Only two clinical trials have investigated pretreatment (initiation of treatment before angiography) with P2Y12 inhibitors27,45:

- ATLANTIC trial investigating ticagrelor pretreatment in patients with STEMI49

- ACCOAST trial investigating pasugrel pretreatment in patients with NSTE-ACS50

Neither the ATLANTIC nor the ACCOAST trial showed any benefit of pretreatment with ticagrelor or prasugrel, respectively. For patients with STEMI, there is general consensus that P2Y12 inhibitor treatment should be initiated as early as possible, although ESC guidelines recommend delaying treatment if a diagnosis of STEMI is not clear or the anatomy is not known27,45. For patients with NSTE-ACS, ACC/AHA guidelines recommend initiating therapy before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)28. The latest ESC guidelines no longer recommend pretreatment with P2Y12 inhibitors for patients with NSTE-ACS in whom coronary anatomy is not known and PCI is planned, but allow for clinical judgement based on bleeding risk15.

Before the ESC guidelines were updated in 2020, ESC and ACC/AHA were in agreement that either prasugrel or ticagrelor were the P2Y12 inhibitors of choice for ACS48. Clopidogrel was recommended only in the event that prasugrel or ticagrelor were contraindicated or bleeding risk was unacceptably high. The 2020 ESC guidelines incorporated the findings of the ISAR-REACT-5 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 5) trial, which showed that prasugrel was superior to ticagrelor in reducing ischaemic risk without increasing bleeding risk in patients with ACS15,51. Overall, the 2020 ESC guidelines for NSTE-ACS recommend greater individualisation of antiplatelet treatment based on ischaemic/thrombotic events and bleeding complications and advise on long-term oral anticoagulation management15.

The new key recommendations of the 2020 ESC guidelines for antiplatelet therapy in patients with NSTE-ACS are15:

- Prasugrel should be considered in preference to ticagrelor for NSTE-ACS patients who proceed to PCI.

- Routine pretreatment with a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor is not recommended for patients in whom the coronary anatomy is not known and early invasive management is planned; however, it may be considered in patients who do not have a high bleeding risk.

- De-escalation of P2Y12 inhibitor treatment (e.g. with a switch from prasugrel or ticagrelor to clopidogrel) may be considered as an alternative DAPT strategy, especially for ACS patients deemed unsuitable for potent platelet inhibition. De-escalation may be based on clinical judgment or guided by platelet function testing or CYP2C19 genotyping, depending on the patient’s risk profile and availability of respective assays (Figure 7).

- In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) (CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥1 in men and ≥2 in women), after a short period of triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT) (up to 1 week from the acute event), dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT) is recommended as the default strategy using a non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) at the recommended dose for stroke prevention and single oral antiplatelet agent (preferably clopidogrel).

- Discontinuation of antiplatelet treatment in patients treated with oral anticoagulants (OACs) is recommended after 12 months.

- DAT with an OAC and either ticagrelor or prasugrel may be considered as an alternative to TAT with an OAC, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with a moderate or high risk of stent thrombosis, irrespective of the type of stent used.

Figure 7. De-escalation or escalation of P2Y12 inhibitor treatment in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (Adapted52). ACS, acute coronary syndrome; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PFT, platelet function testing.

Download this infographic that summarises the 2020 ESC and 2021 ACC/AHA guidelines for antiplatelet therapy in ACS.

Download infographic

Challenges in antiplatelet therapy selection in ACS

Selection of P2Y12 inhibitor

There are multiple factors that should be considered when selecting a P2Y12 inhibitor for a given patient. These include patient characteristics and comorbidities, weighting of benefit versus side effects, potential drug-drug interactions and pharmacokinetics. These factors should be considered alongside label indications and clinical guideline recommendations. Whilst clinical guidelines have been immensely improved over the decades, shortcomings can compromise optimal care.

Since publication of the 2020 ESC NSTE-ACS guidelines, leading cardiology experts have voiced concerns on the evidence for the recommendation favouring prasugrel over ticagrelor in patients with NSTE-ACS who proceed to PCI53–56

The 2020 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS) gave a strong level of recommendation (IIa) in favour of prasugrel over ticagrelor in patients with NSTE-ACS who proceed to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)15. This recommendation was based on a prospective head-to-head study, ISAR-REACT 5, which concluded that prasugrel was superior to ticagrelor at preventing major adverse ischaemic events15,51. The 2021 ACC/AHA guideline for coronary artery revascularization has not adopted this recommendation and continues to allow for the use of either prasugrel or ticagrelor47.

The ISAR-REACT-5 study, published in 2019, was the first randomised trial to compare ticagrelor with prasugrel51. Patients with ACS undergoing invasive therapy were randomised to receive ticagrelor (loading dose 180 mg, maintenance dose 90 mg twice daily; n = 2012) or prasugrel (loading dose 60 mg, maintenance dose 10 mg daily; n = 2006) and were followed up for 1 year. The maintenance dose of prasugrel was reduced to 5 mg for patients older than 75 years or who weighed less than 60 kg. Patients with a history of stroke, TIA or intracranial haemorrhage were excluded. The primary outcome of death, myocardial infarction or stroke at 1 year occurred in 9.3% of the ticagrelor group and 6.9% of the prasugrel group (P=0.006) with no significant difference in bleeding51. The 2020 ESC guidelines gave a strong level of recommendation (IIa) in favour of prasugrel over ticagrelor in patients with NSTE-ACS who proceed to PCI15. Since publication of the 2020 ESC guidelines, however, leading cardiology experts have voiced concerns about recommendations based only on the ISAR-REACT 5 study, suggesting that equipoise remains between the ticagrelor- and prasugrel-based strategies and more data are needed to settle the debate53–55.

Find out more in our expert roundtable discussion on the 2020 ESC guidelines

Several concerns on the implications of the ISAR-REACT 5 study have been raised53–56:

- The ISAR-REACT 5 trial did not directly compare ticagrelor with prasugrel; rather, it was a comparison of treatment strategies for patients with NSTE-ACS, as all patients received ticagrelor pretreatment, whereas patients with NSTE-ACS did not receive prasugrel pretreatment56.

- In addition to its open-label design, the trial was performed in only two countries with an imbalance in enrolling centres (21 centres in Germany and 2 centres in Italy), which could have some impact on the outcomes, however minor.

- At discharge, about 19% of patients in each group did not receive the assigned drug for various reasons. After discharge 15% of patients on ticagrelor and 12% on prasugrel discontinued treatment. This rate of discontinuation may have affected the final results by overestimating the beneficial effect of prasugrel56.

- After discharge, physicians prescribed commercially available ticagrelor or prasugrel, and patients had to purchase the drugs themselves. No specific method for verifying adherence, such as pill count or medication event monitoring systems, was reported. As patient-reported drug adherence has been previously shown to have significant discrepancies57,58, the true medication adherence in the trial may have been lower than that reported55.

- More patients in the prasugrel group (233) than those in the ticagrelor group (23) were excluded from the safety endpoint analysis, raising questions about the safety profile of prasugrel, compared with ticagrelor.

More controversies also stem from the results of a prespecified ISAR-REACT 5 subgroup analysis of ticagrelor versus prasugrel efficacy according to diabetic status59. In this subgroup of patients with high ischaemic risk and poor antiplatelet response, the efficacy of prasugrel and ticagrelor in reducing ischaemic events (a composite of death, myocardial infarction or stroke) was comparable up to 1 year after randomisation.

Whilst the ISAR-REACT 5 study supports the concept of individualised care for NSTE-ACS patients undergoing PCI, more data are needed to support a preferred drug or strategy54

Guidelines from the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK also considered the evidence provided by the ISAR-REACT 5 trial. For patients with STEMI, NICE recommends prasugrel if PCI is planned and the patients are not on oral anticoagulant therapy60. If medical management is planned, NICE recommends ticagrelor in preference to prasugrel, or clopidogrel if bleeding risk is high60. For patients with NSTE-ACS undergoing PCI, NICE acknowledges the ISAR-REACT 5 findings favouring prasugrel over ticagrelor, but for practical reasons, recommends ticagrelor or clopidogrel60. The rationale for this is that in the UK, there can be delays of up to 72 hours before coronary angiography is performed60. This may preclude the use of prasugrel because, in the UK, it is not licenced for use before coronary anatomy is known60. ACC/AHA and Australian/New Zealand guidelines have not been updated since publication of the ISAR REACT 5 study and do not specify a preference of prasugrel over ticagrelor among patients with confirmed ACS at intermediate to very high- risk of recurrent ischaemic events61,62.

Overall, while clinical guidelines are updated and improved as new information emerges, concerns raised by experts in the field should be taken seriously and discussed openly

Find out more in our expert roundtable discussion on the 2020 ESC guidelines

Test yourself with our Patient Focus case studies presented by experts

De-escalation of DAPT

The latest ESC guidelines state that de-escalation of P2Y12 inhibitor treatment (e.g. with a switch from prasugrel or ticagrelor to clopidogrel) may be considered as an alternative DAPT strategy, especially for ACS patients deemed unsuitable for potent platelet inhibition15. There are many variables that should be considered when favouring de-escalation of DAPT (Figure 8)15.

Figure 8. Variables that should be considered for favouring de-escalation of DAPT (Adapted15).

However, it is important to note that there is a potential for increased ischaemic risk with a uniform de-escalation of P2Y12 receptor inhibition after PCI, particularly if performed early (<30 days) after the index event63. Indeed, dedicated large-scale trials on a uniform and unguided DAPT de-escalation are lacking, and the available data on uniform de-escalation are conflicting63,64.

DAPT de-escalation guided by either platelet function testing or CYP2C19-directed genotyping may be considered as an alternative to 12 months of potent platelet inhibition, especially for patients deemed unsuitable for maintained potent platelet inhibition65,66

After deciding to de-escalate to clopidogrel, it is possible to do this either by giving a loading dose or not63. There have not been any randomised trials powered for clinical outcomes investigating this, but expert consensus papers give recommendations based on pharmacodynamic studies. Whether or not a loading dose is given is based on the timing of de-escalation and the P2Y12 inhibitor used prior to de-escalation (Figure 9). When de-escalating in the early phase (≤30 days from the index event), a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel should be administered 24 h after the last dose of prasugrel or ticagrelor52. In a sub-analysis of the POPULAR Genetics trial, this method seemed safe with no bleeding and thrombotic events in 172 patients who switched to clopidogrel within seven days after STEMI66. When de-escalating from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in the late phase (>30 days from the index event), a 600 mg loading dose 24 h after the last dose of ticagrelor is recommended, while it is not recommended to use a new loading dose when switching from prasugrel to clopidogrel in the late phase67. If de-escalating due to bleeding or bleeding concerns, a 75 mg clopidogrel dose could be considered instead of a loading dose irrespective of the phase or initial P2Y12 inhibitor68,69.

Figure 9. De-escalation dosing recommendation for clopidogrel (Adapted52). IE, index event.

Evidence for antiplatelet therapy in NSTE-ACS

Patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) account for approximately two-thirds of all hospital admissions for ACS70,71.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is recommended for patients with NSTE-ACS for 12 months, unless there are contraindications or an unacceptably high risk of bleeding15,61

Ticagrelor has a faster and more consistent onset of action, compared with clopidogrel, in addition to a quicker offset of action with a more rapid recovery of platelet function72. Ticagrelor was found to be more effective than clopidogrel in patients with moderate-to-high risk NSTE-ACS in the PLATO trial73.

The long-term use of antiplatelet therapy in patients with prior myocardial infarction has been investigated in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Prior Heart Attack Using Ticagrelor Compared to Placebo on a Background of Aspirin–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 54 (PEGASUS-TIMI 54) trial74. Here, the hypothesis that long-term therapy with ticagrelor added to low-dose aspirin would reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events among stable patients with a history of myocardial infarction was tested. Results showed that, in patients with a myocardial infarction more than 1 year previously, long-term treatment with ticagrelor significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or stroke and increased the risk of major bleeding74. This was true for both ticagrelor doses tested (90 mg and 60 mg) (Figure 10)74.

Figure 10. Kaplan–Meier rates of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and stroke during the three years follow up in the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial (Adapted74). CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Prasugrel also has a faster onset and is more potent than clopidogrel25. The TRITON-TIMI 38 trial demonstrated that patients receiving prasugrel had fewer recurrent cardiovascular events and less stent thrombosis but more bleeding complications, compared with clopidogrel26,75. Therefore, the 2016 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that it is reasonable to choose prasugrel over clopidogrel for maintenance therapy in patients treated with DAPT after stent implantation, unless they are at high risk of bleeding or have contraindications38. On the other hand, results from TRITON-TIMI 38 trial showed that prasugrel increased the risk of major and fatal bleeding in patients with prior stroke or TIA26. In addition, the study showed no apparent benefit for the use of prasugrel over clopidogrel in patients aged above 75 years or with low body weight (<60 kg)26.

On the basis of these studies, clopidogrel is generally used when ticagrelor or prasugrel are not suitable, for example, in those with an indication for oral anticoagulation and in those with prior intracranial bleeding15. Clopidogrel is used in combination with aspirin at a maintenance dose of 75 mg daily in patients with NSTE-ACS15.

Recommended doses of antiplatelet drugs are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Antiplatelet dosing regimen for patients with NSTE-ACS (Adapted15). Note: see guidelines for full notes on dosing recommendations. iv, intravenous.

| *Use with caution | ||

| Drug | Loading dose | Maintenance dose |

| Aspirin | 150–300 mg (oral) or 75–250 mg (iv) |

75–100 mg daily |

| Prasugrel | 60 mg | 10 mg daily 5 mg once daily for patients >75 years* or <60 kg |

| Ticagrelor | 180 mg | 90 mg twice daily |

| Clopidogrel | 300–600 mg | 75 mg once daily |

| Cangrelor | 30 µg/kg bolus | 4 µg/kg for 2 hours or duration of procedure |

It has been proposed that, because of its association with major bleeding76, the ADP-binding enzyme creatine kinase (CK) should be estimated in studies of patients treated for NSTE-ACS77,78. Major bleeding is one of the most common non-cardiac causes of mortality in NSTE-ACS. Therefore, it is important to identify patients at risk for haemorrhagic complications when designing a treatment plan with antiplatelet therapy. In this context, the application of the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk (ARC-HBR) could be a useful tool79,80. Table 3 shows the major and minor criteria for high bleeding risk according to the ARC-HBR at the time of percutaneous coronary intervention. Bleeding risk is considered high if at least one major or two minor criteria are met15.

Table 3. Major and minor criteria for high bleeding risk according to the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk (ARC-HBR) at the time of percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with NSTE-ACS. Bleeding risk is high if at least one major or two minor criteria are met (Adapted15). CKD, chronic kidney disease; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; OAC, oral anti-coagulant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

| * This excludes vascular protection doses † Baseline thrombocytopenia is defined as thrombocytopenia before PCI ‡ Active malignancy is defined as diagnosis within 12 months and/or ongoing requirement for treatment (including surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy) § National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score >5 |

|

| Major | Minor |

| • Anticipated use of long-term OAC* | • Age ≥ 75 years |

| • Severe or end-stage CKD (eGFR <30 mL/min) | • Moderate CKD (eGFR 30–59 mL/min) |

| • Haemoglobin <11 g/dL | • Haemoglobin 11–12.9 g/dL for men or 11–11.9 g/dL for women |

| • Spontaneous bleeding requiring hospitalisation and/or transfusion in the past 6 months or at any time, if recurrent | • Spontaneous bleeding requiring hospitalisation and/or transfusion within the past 12 months not meeting the major criterion |

| • Moderate or severe baseline thrombocytopenia† (platelet count <100 x 109/L) |

• Chronic use of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids |

| • Chronic bleeding diathesis | • Any ischaemic stroke at any time not meeting the major criterion |

| • Liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension | |

| • Active malignancy‡ (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) within the past 12 months |

|

| • Previous spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage (at any time) • Previous traumatic intracranial haemorrhage within the past 12 months • Presence of a brain arteriovenous malformation • Moderate or severe ischaemic stroke§ within the past 6 months |

|

| • Recent major surgery or major trauma within 30 days prior to PCI • Non-deferrable major surgery on DAPT |

|

Evidence for antiplatelet therapy in STEMI

Antiplatelet therapy is an essential component of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) management.

Current guidelines state that people with acute STEMI who are having primary PCI should be offered60:

- Prasugrel, as part of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin, if they are not already taking an oral anticoagulant

- Clopidogrel, as part of DAPT with aspirin, if they are already taking an oral anticoagulant

Clopidogrel in STEMI

Clopidogrel use in STEMI was first evaluated in the CLARITY-TIMI 28 study in 2005, which randomised 3,491 patients with STEMI treated with a fibrinolytic agent and aspirin (150–325 mg loading, then 75–162 mg daily) to clopidogrel (300 mg loading, then 75 mg daily) or placebo81. At 30 days, clopidogrel reduced the composite endpoint (cardiovascular death, recurrent myocardial infarction, recurrent ischaemia needing PCI) by 20%, with similar rates of major bleeding and intracranial haemorrhage81. These results were further confirmed by the COMMIT study82.

After establishing the clinical benefits of DAPT with clopidogrel, more trials revealed variability in individual responses, leading to suboptimal responses. These can be due to genetic factors, clinical factors (drug interactions, poor absorption), or cellular factors (P2Y12 pathway upregulation)83.

Prasugrel in STEMI

In the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial, 3,534 patients had STEMI26,75. Prasugrel was associated with a greater improvement than clopidogrel in the primary endpoint at 15 months (10 vs 12.4%, HR 0.79, P=0.02), significantly greater reduction in both secondary endpoints (urgent target vessel revascularisation and stent thrombosis)26,75. However, it is important to note that in the main TRITON-TIMI 38 study, the reported benefits came at the expense of significantly increased major bleeding (2.4 vs 1.8%, HR 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03–1.68), life-threatening bleeding and even fatal bleeding26. In an important subsequent analysis of the main trial, there was no accrued clinical benefit from prasugrel in the following groups: history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), age 75 years or greater, and weight 60 kg or less75. Those with stroke or TIA were harmed by prasugrel administration (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.02–2.32), including increased intracranial haemorrhage (2.3% vs none on clopidogrel, P=0.02)75.

Overall, prasugrel is a more efficacious and reasonably safe antiplatelet therapy in patients with STEMI treated with PCI, compared with clopidogrel75. However, prasugrel is contraindicated in patients with a history of stroke or TIA. It is generally not recommended for people age 75 years or older or who weigh <60 kg27,45.

Ticagrelor in STEMI

Ticagrelor was compared with clopidogrel in patients with ACS in the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) Study31. Patients were randomised to receive either ticagrelor (180 mg loading, 90 mg twice daily maintenance) or clopidogrel (300–600 mg loading, 75 mg daily). Overall, the results for the STEMI subgroup analysis of PLATO were consistent with the main trial31,84. Of the 18,624 patients, 7,544 patients were diagnosed with STEMI (or left bundle-branch block)84. At 12 months, the primary endpoint was reduced in the ticagrelor and clopidogrel groups, but the difference was not statistically significant (10.8 vs 9.4%; P=0.07)84. When patients with a final diagnosis of STEMI (not just at presentation) were included, however, the primary endpoint was reduced further in the ticagrelor group and the difference between the groups was significantly different (9.3 vs 11.0%; P=0.02)84. Ticagrelor also had a significantly greater effect than clopidogrel in reducing several of the secondary endpoints in the STEMI population, including a composite of cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction (8.4 vs 10.2%, P=0.01); all arterial thrombotic events (13.3% vs 15.0%; P=0.03); the incidence of myocardial infarction alone (4.7% vs 5.8%; P=0.03); and definite stent thrombosis (1.6 vs 2.4%; P=0.03)84.

Compared with the CURE trial and TRITON-TIMI 38 studies, the results of PLATO are notable because stronger platelet inhibition from ticagrelor did not result in increased bleeding84. This, together with the reduction in mortality, led to an indication of preference for ticagrelor over clopidogrel in the 2016 ACC Guidelines38.

References

- Makki N, Brennan TM, Girotra S. Acute coronary syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;30(4):186–200.

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;76(25):2982–3021.

- Montalescot G. Platelet biology and implications for antiplatelet therapy in atherothrombotic disease. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2011;17(4):371–380.

- White HD. Unmet therapeutic needs in the management of acute ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80(4A):2B-10B.

- Kamran H, Jneid H, Kayani WT, Virani SS, Levine GN, Nambi V, et al. Oral Antiplatelet Therapy After Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1545–1555.

- Chaabane C, Otsuka F, Virmani R, Bochaton-Piallat M-L. Biological responses in stented arteries. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99(2). doi:10.1093/cvr/cvt115.

- Franchi F, Angiolillo DJ. Novel antiplatelet agents in acute coronary syndrome. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2015;12(1):30–47.

- Jneid H, Bhatt DL, Corti R, Badimon JJ, Fuster V, Francis GS. Aspirin and Clopidogrel in Acute Coronary Syndromes: Therapeutic Insights From the CURE Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(10):1145–1153.

- Fuster V, Sweeny JM. Aspirin. Circulation. 2011;123(7):768–778.

- Baigent C, Collins R, Appleby P, Parish S, Sleight P, Peto R. ISIS-2: 10 year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. The ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1998;316(7141). doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1337.

- Risk of myocardial infarction and death during treatment with low dose aspirin and intravenous heparin in men with unstable coronary artery disease. The RISC Group. Lancet. 1990;336(8719).

- Cairns JA, Gent M, Singer J, Finnie KJ, Froggatt GM, Holder DA, et al. Aspirin, sulfinpyrazone, or both in unstable angina. Results of a Canadian multicenter trial. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(22). doi:10.1056/NEJM198511283132201.

- Lewis HD, Davis JW, Archibald DG, Steinke WE, Smitherman TC, Doherty JE, et al. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. Results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(7). doi:10.1056/NEJM198308183090703.

- Théroux P, Ouimet H, McCans J, Latour JG, Joly P, Lévy G, et al. Aspirin, heparin, or both to treat acute unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(17). doi:10.1056/NEJM198810273191701.

- Collet J-P, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. European Heart Journal. 2021;42(14):1289–1367.

- CURRENT-OASIS 7 Investigators, Mehta SR, Bassand J-P, Chrolavicius S, Diaz R, Eikelboom JW, et al. Dose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(10):930–42.

- Rollini F, Franchi F, Angiolillo DJ. Switching P2Y12-receptor inhibitors in patients with coronary artery disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2016;13(1):11–27.

- Feng KMWK. Cangrelor in clinical use. Future Cardiology. 2020;12(2).

- Sangkuhl K, Klein TE, Altman RB. Clopidogrel pathway. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 2010;20(7). doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283385420.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010746.

- Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJG, Bertrand ME, Lewis BS, Natarajan MK, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. The Lancet. 2001;358(9281):527–533.

- Vranckx P, Lewalter T, Valgimigli M, Tijssen JG, Reimitz P-E, Eckardt L, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of an edoxaban-based antithrombotic regimen in patients with atrial fibrillation following successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent placement: Rationale and design of the ENTRUST-AF PCI trial. Am Heart J. 2018;196. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2017.10.009.

- Giorgi MA, Di Girolamo G, González CD. Nonresponders to clopidogrel: pharmacokinetics and interactions involved. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(14). doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.498820.

- Layne K, Ferro A. Antiplatelet Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndrome | ECR Journal. Eur Cardiol Rev. 2017;12(1):33–37.

- Zeymer U. Oral Antiplatelet Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndromes: Recent Developments. Cardiology and Therapy. 2013;2(1):47.

- Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706482.

- O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of st-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78-140.

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-st-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):e344–e426.

- FDA. Prasugrel highlights of prescribing information. Food and Drug Administration. 2009. www.fda.gov/medwatch. Accessed 7 December 2021.

- Amico F, Amico A, Mazzoni J, Moshiyakhov M, Tamparo W. The evolution of dual antiplatelet therapy in the setting of acute coronary syndrome: ticagrelor versus clopidogrel. Postgrad Med. 2016;128(2). doi:10.1080/00325481.2016.1118351.

- Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(11):1045–1057.

- Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, Cohen DJ, Angiolillo DJ, Briguori C, et al. Ticagrelor with or without Aspirin in High-Risk Patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908419.

- Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Hamm CW, Stone GW, Gibson CM, Mahaffey KW, et al. Effect of cangrelor on periprocedural outcomes in percutaneous coronary interventions: a pooled analysis of patient-level data. Lancet. 2013;382(9909). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61615-3.

- Bhatt DL, Stone GW, Mahaffey KW, Gibson CM, Steg PG, Hamm CW, et al. Effect of platelet inhibition with cangrelor during PCI on ischemic events. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300815.

- Harrington RA, Stone GW, McNulty S, White HD, Lincoff AM, Gibson CM, et al. Platelet Inhibition with Cangrelor in Patients Undergoing PCI. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(24):2318–2329.

- de Luca L, Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Capodanno D, Angiolillo DJ. Cangrelor: Clinical Data, Contemporary Use, and Future Perspectives. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(13). doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.022125.

- Sabouret P, Savage MP, Fischman D, Costa F. Complexity of Antiplatelet Therapy in Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2021;21(1). doi:10.1007/s40256-020-00414-0.

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2016;134(10). doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000404.

- Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409312.

- Tersalvi G, Biasco L, Cioffi GM, Pedrazzini G. Acute Coronary Syndrome, Antiplatelet Therapy, and Bleeding: A Clinical Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(7):1–20.

- Costa F, van Klaveren D, James S, Heg D, Räber L, Feres F, et al. Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score: a pooled analysis of individual-patient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet. 2017;389(10073). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30397-5.

- Yeh RW, Secemsky EA, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SLT, Gershlick AH, Cohen DJ, et al. Development and Validation of a Prediction Rule for Benefit and Harm of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Beyond 1 Year After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1735–1749.

- Kumbhani DJ, Cannon CP, Beavers CJ, Bhatt DL, Cuker A, Gluckman TJ, et al. 2020 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation or Venous Thromboembolism Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(5). doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.011.

- Watanabe H, Domei T, Morimoto T, Natsuaki M, Shiomi H, Toyota T, et al. Effect of 1-Month Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Followed by Clopidogrel vs 12-Month Dual Antiplatelet Therapy on Cardiovascular and Bleeding Events in Patients Receiving PCI: The STOPDAPT-2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(24). doi:10.1001/jama.2019.8145.

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2). doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393.

- Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet J-P, Costa F, Jeppsson A, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(3). doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419.

- Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(3):e18–e114.

- Capodanno D, Alfonso F, Levine GN, Valgimigli M, Angiolillo DJ. ACC/AHA Versus ESC Guidelines on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: JACC Guideline Comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(23):2915–2931.

- Montalescot G, van ’t Hof AW, Lapostolle F, Silvain J, Lassen JF, Bolognese L, et al. Prehospital ticagrelor in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1407024.

- Montalescot G, Bolognese L, Dudek D, Goldstein P, Hamm C, Tanguay J-F, et al. Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(11). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1308075.

- Schüpke S, Neumann F-J, Menichelli M, Mayer K, Bernlochner I, Wöhrle J, et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908973.

- Claassens DMF, Sibbing D. De-Escalation of Antiplatelet Treatment in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Review of the Current Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, Vol 9, Page 2983. 2020;9(9):2983.

- Sulzgruber P, Niessner A. Prasugrel vs. ticagrelor after acute coronary syndrome: a critical appraisal of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020;6(5). doi:10.1093/ehjcvp/pvz077.

- Angoulvant D, Sabouret P, Savage MP. NSTE-ACS ESC Guidelines Recommend Prasugrel as the Preferred P2Y12 Inhibitor: A Contrarian View. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2021;21(5). doi:10.1007/s40256-021-00471-z.

- Kubica J, Jaguszewski M. ISAR-REACT 5 - What have we learned? Cardiol J. 2019;26(5). doi:10.5603/CJ.a2019.0090.

- Arslan F, Damman P, Zwart B, Appelman Y, Voskuil M, de Vos A, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation : Recommendations and critical appraisal from the Dutch ACS and Interventional Cardiology working groups. Neth Heart J. 2021;29(11). doi:10.1007/s12471-021-01593-4.

- Shi L, Liu J, Fonseca V, Walker P, Kalsekar A, Pawaskar M. Correlation between adherence rates measured by MEMS and self-reported questionnaires: a meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-8-99.

- Kubica A, Kasprzak M, Obońska K, Fabiszak T, Laskowska E, Navarese EP, et al. Discrepancies in assessment of adherence to antiplatelet treatment after myocardial infarction. Pharmacology. 2015;95(1–2). doi:10.1159/000371392.

- Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A, Menichelli M, Neumann F-J, Wöhrle J, Bernlochner I, et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes and Diabetes Mellitus. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(19). doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.07.032.

- NICE. Acute coronary syndromes NICE guideline [NG185]. 2020.

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Guyton RA, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(23). doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000031.

- Chew DP, Scott IA, Cullen L, French JK, Briffa TG, Tideman PA, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25(9). doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2016.06.789.

- de Luca L, D’Ascenzo F, Musumeci G, Saia F, Parodi G, Varbella F, et al. Incidence and outcome of switching of oral platelet P2Y12 receptor inhibitors in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SCOPE registry. EuroIntervention. 2017;13(4). doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-17-00092.

- Cuisset T, Deharo P, Quilici J, Johnson TW, Deffarges S, Bassez C, et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: the TOPIC (timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome) randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(41). doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx175.

- Sibbing D, Aradi D, Jacobshagen C, Gross L, Trenk D, Geisler T, et al. Guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TROPICAL-ACS): a randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10104). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32155-4.

- Claassens DMF, Vos GJA, Bergmeijer TO, Hermanides RS, van ’t Hof AWJ, van der Harst P, et al. A Genotype-Guided Strategy for Oral P2Y12 Inhibitors in Primary PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1907096.

- Claassens DMF, Sibbing D. De-Escalation of Antiplatelet Treatment in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Review of the Current Literature. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):1–10.

- Angiolillo DJ, Rollini F, Storey RF, Bhatt DL, James S, Schneider DJ, et al. International Expert Consensus on Switching Platelet P2Y12 Receptor-Inhibiting Therapies. Circulation. 2017;136(20). doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031164.

- Sibbing D, Aradi D, Alexopoulos D, ten Berg J, Bhatt DL, Bonello L, et al. Updated Expert Consensus Statement on Platelet Function and Genetic Testing for Guiding P2Y12 Receptor Inhibitor Treatment in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(16). doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2019.03.034.

- Bob-Manuel T, Ifedili I, Reed G, Ibebuogu UN, Khouzam RN. Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Comprehensive Review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2017;42(9). doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2017.04.006.

- Kotecha T, Rakhit RD. Acute coronary syndromes. Clin Med (Lond). 2016;16(Suppl 6). doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.16-6-s43.

- Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Butler K, Tantry US, Gesheff T, Wei C, et al. Randomized double-blind assessment of the ONSET and OFFSET of the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with stable coronary artery disease: the ONSET/OFFSET study. Circulation. 2009;120(25). doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.912550.

- Wallentin L, James S, Storey RF, Armstrong M, Barratt BJ, Horrow J, et al. Effect of CYP2C19 and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on outcomes of treatment with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes: a genetic substudy of the PLATO trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9749). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61274-3.

- Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, Steg PG, Storey RF, Jensen EC, et al. Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500857.

- Montalescot G, Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, et al. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2009;373(9665):723–731.

- Brewster LM, Fernand J. Creatine kinase during non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes is associated with major bleeding. Open Heart. 2020;7(2). doi:10.1136/openhrt-2020-001281.

- Brewster LM. Because of its association with major bleeding the ADP-binding enzyme creatine kinase should be estimated in studies of patients treated for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS). Eur Heart J. 2021;42(23). doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa905.

- Collet J-P, Thiele H. Major bleeding and the ADP-binding enzyme creatine kinase in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(23). doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa908.

- Natsuaki M, Morimoto T, Shiomi H, Yamaji K, Watanabe H, Shizuta S, et al. Application of the Academic Research Consortium High Bleeding Risk Criteria in an All-Comers Registry of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(11). doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.119.008307.

- Ueki Y, Bär S, Losdat S, Otsuka T, Zanchin C, Zanchin T, et al. Validation of the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk (ARC-HBR) criteria in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and comparison with contemporary bleeding risk scores. EuroIntervention. 2020;16(5). doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-20-00052.

- Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, López-Sendón JL, Montalescot G, Theroux P, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(12). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050522.

- Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, Xie JX, Pan HC, Peto R, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9497). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67660-X.

- Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, Alfonso F, Macaya C, Bass TA, et al. Variability in individual responsiveness to clopidogrel: clinical implications, management, and future perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(14). doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.044.

- Steg PG, James S, Harrington RA, Ardissino D, Becker RC, Cannon CP, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes intended for reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A platelet inhibition and patient outcomes (PLATO) trial subgroup analysis. Circulation. 2010;122(21):2131–2141.

This content has been developed independently by Medthority who previously received educational funding from AstraZeneca in order to help provide its healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.