Managing High-Risk NMIBC

Transcript: BladderPath trial at ESMO 2025

Nick James, BSc, MBBS, PhD, FRCP, FRCR

Interview recorded October 2025. All transcripts are created from interview footage and directly reflect the content of the interview at the time. The content is that of the speaker and is not adjusted by Medthority.

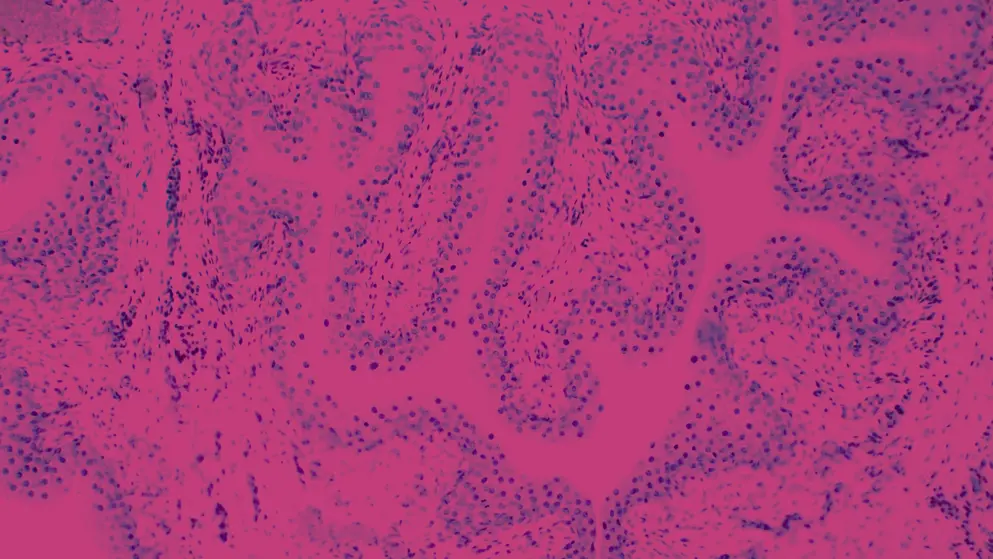

- BladderPath trial was conceived basically building on work that's was done a little while ago now with prostate cancer, with MRI. And what that shows is that if you do an MRI scan before you start sticking needles in the prostate, you make better decisions. In fact, half the time you decide you need to do a biopsy at all. So we wanted to build on that. And so for bladder cancer, it's the standard of care is that everybody with a bladder mass gets a TURBT, transurethral resection of the bladder tumor. So it's done with a rigid cystoscope, and the tumor is kind of scooped out, kind of piecemeal.

And the aim is to take as much of the tumor out as you can, and to include muscle in that. And so it's a very curious procedure because it's giving you histology. So it's like a very big, slightly haphazard biopsy. It's giving you stage, because we want to know if the tumor's against the muscle or not. If the tumor is not against the muscle, then it's also treatment. So it's three procedures wrapped into one. Now, for the 75% of patients who are non-muscle invasive, that kinda works pretty well, but for the 25% who are muscle invasive, it really does not work very well at all, because often, especially more junior surgeons will not manage to get muscle in their specimen. And so you end up having to re-resect to find out whether or not it is indeed muscle invasive, so that builds delay into the system. And it typically takes around 100 days to get through the, sort of the re-resections, and the, you know, referring from a hospital to another for the procedure, one in one hospital, procedure two in another.

And that's global, it's not a UK specific thing. So we hypothesized that if you did an MRI scan in, just in the worst 50% of the patients, that you could triage patients who are likely to be muscle invasive and need one pathway from patients who are actually non-muscle invasive and need another pathway, i.e., resection, endoscopic resection. So we conceived of that a while back, and we had a three stage trial, three stages, feasibility, intermediate, which is what did we do to time to treatment as we predicted it would come down, and the final stage is what I presented yesterday, was what did the impact, what did the faster treatment, which we showed, do to the overall rates of recurrence.

Yeah, so the key findings, as I said, three stages, feasibility, we've shown it was feasible. The interim outcome was time to treatment. We aim to reduce it by 30 days for the time to muscle invasive bladder cancer treatment with a secondary outcome of no impact on non-muscle invasive outcomes 'cause we don't wanna make one a bit better at the expense of another getting worse. And both of those endpoints were met, and met with a lot of room to spare, actually. So the average time to treatment came down from about just under 100 days to around 45 days, so it halved six weeks, so a big improvement. And so what we were showing yesterday was the failure-free survival, bladder cancer specific survival, and overall survival outcomes. So for all three of those outcome measures, underpowered sadly, 'cause the treatment was just killed by the pandemic, by COVID.

But nonetheless, we had two-year follow-up on all the patients. So for all three of those, the hazard ratio was under one, which favors the MRI arm. And, but for failure-free survival, the constant was crossed one. But for bladder cancer specific survival, it was statistically significant. The hazard ratio was under 0.5, but the constant interval was not crossing one. So we showed a statistically significant improvement with all the limitations of sample size, but nonetheless, it was statistical improvement in bladder cancer specific survival. Overall survival just failed to meet statistical significance, partly because 45% of the deaths were not due to bladder cancer, so they were not gonna be improved.

And the other causes of death were very interesting. So, around 1/3 of the patients had other smoking related cancers, lung cancer, esophageal, mouth cancer, things like that. Around 1/3 of the patients died of cardiovascular or pulmonary causes, consistent with these being 70-year-old lifelong smokers and so on. And just a couple of other cancers, like one patient died of leukemia. So, this is very important in the debate you have around bladder preservation or not, because these patients, they're not, the bladder cancer is not the sole risk for many of these patients. So those are the main findings. We think they're very important because, you know, we've shown that putting the MRI in improves the time to treatment substantially, but we've now shown that it potentially is improving bladder cancer outcomes, as well. Well, I think they're potentially quite big because we showed that adding an MRI scan speeds time to treatment, and we think probably also makes the TURBTs that did happen.

So 85% of the patients on the MRI arm had a TURBT as well, probably a much more limited one than if they had that as their sole staging test. So it brings benefits in terms of theater time, extensive resection morbidity. About one in six or one in seven patients did not need a TURBT, for example, because they went straight to palliative care or straight to chemotherapy because they were metastatic, things like that. Because an MRI is cheaper, certainly in NHS, than a TURBT, you know, it's a surgical procedure, a surgeon, an anesthetist theater, nurse's theater, other theater staff, and so on, you only need to eliminate one in 10 TURBTs to pay for all of the MRIs on the pathway. So we eliminated more than that and still improved the outcomes. So overall, the trial was cost-saving in the centers that ran it. Now, you have got issues around increasing MRI usage.

And of course, the MRI people will say we haven't got enough capacity, but I think there are ways around that as well. So like, we currently do MRIs of all our prostate patients before they have a biopsy. So that's far bigger number of MRIs than the number of bladders that we would need to do. It's a much commoner cancer, prostate cancer, than bladder cancer. But also, we're thinking we're gonna go through a shorter, faster sequence for our prostate MRIs that will take 10 minutes instead of 25. So there are other things afoot that will increase MRI capacity without having to buy more MRI scans. And probably, you can AI read the prostate scans as well, so you don't need more radiologists to do it. So we think there are ways to flex the capacity we have to accommodate it. Overall, the patient benefits are huge.

They're getting treated faster. That's a benefit straight up. But if they're also looking like they might be getting better clinical outcomes, then that really starts looking for me like a no-brainer. Clearly, there's an effort to implement it. Our network has partly implemented it, so some of the centers are doing it, some of the centers aren't. And once you start doing it, as happened with prostate MRI, it's kind of obvious it's better. You know, you just make better decisions. Yeah, and that's a very interesting question, and this is not at all uncommon, actually. You know, you're faced with, you've apparently had successful treatments already, and now you're told you're needing maybe a couple of years of BCG, and it's quite unpleasant, yeah, you're having a catheter each time. And we've seen this in,, if you look at trials of, for example, adjuvant immunotherapy, you see the same sort of phenomenon.

So like in the NIAGARA trial, which is adjuvant durvalumab, only half the patients got to the end of the durvalumab. In a trial we were recruiting with durvalumab with chemo RT, over half the patient refused, simply if they didn't want all the extra injections. And that's an intravenous injection, and intrathecal cycle injection is significantly worse. It gives you cystitis. It's really not nice. And so I think it requires a very careful discussion around the risks and the benefits. And we know that BCG substantially reduces your risk of having tumor coming back, or worse, tumor progressing to muscle invasive. And we know that currently, the recommended standard of care if that happens is that you lose your bladder. So I think it requires a careful discussion of, yes, there are downsides, but there are downsides to not having it. And those are potentially substantially worse.

And also, I think a lot of the time we, you know, we're forced to counsel patients about all of the potential side effects, but for most of the patients, most of the side effects don't happen or they're not that bad, yet you have to give the worst-case scenario for every side effect, but actually, most patients don't get the worst-case scenario. So it's around giving patients the proper information, and also that's a continuous process. So one of the things that I'll say with chemotherapy, for example, is that a lot of patients don't wanna have chemotherapy. We'll say, well, have the first one, see what it's like. If it's terrible, we're not gonna drag you in and forcibly inject you, clearly, but you may find it's not nearly as bad as you think it's going to be. And you may also find that your problem's getting better if we treat you. So it's a continuous process, reinforcing the benefits, reassuring about side effects, reassuring you can manage side effects.

Developed by EPG Health. This content has been developed independently of the sponsor, Pfizer, which has had no editorial input into the content. EPG Health received funding from the sponsor to help provide healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content. This content is intended for healthcare professionals only.