HRR Mutation Testing in mPC

Transcript: What’s next in HRR testing?

Alex Wyatt, MD, DPhil, and Alicia Morgans, MD, MPH

Interview recorded September 2025. All transcripts are created from interview footage and directly reflect the content of the interview at the time. The content is that of the speaker and is not adjusted by Medthority.

- [Alicia] Hi, and welcome to "Expert exchanges" HRR in metastatic prostate cancer. Today, we're going to talk about future proofing prostate cancer care and what's next in HRR. And I'm so excited to talk today with Dr. Alex Wyatt, who is joining me to really dig into this topic. Thank you so much for being here.

- [Alex] Happy to be here, Alicia, thanks for having me.

- [Alicia] Wonderful, well, you know, let's just jump right in. I think that our understanding of HRR mutations has really evolved quite a bit in the last few years, and I wonder how you see that evolution reshaping the biologic narrative of metastatic prostate cancer. What's new and how is it changing the way we think about this disease?

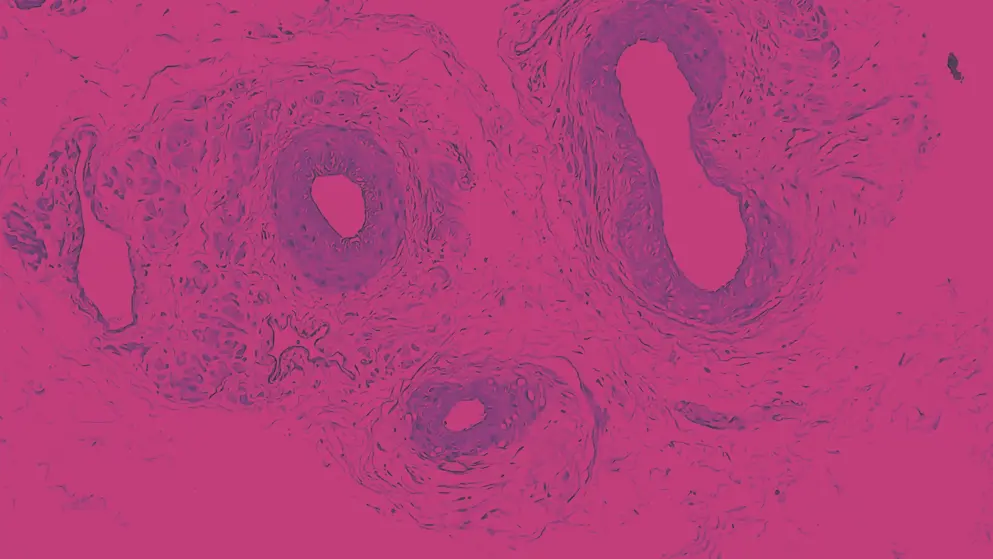

- [Alex] Yeah, it's really is making an impact, I think, as we appraise how prostate cancer arises, spreads, develops resistance. So obviously for many years we've known that there's a fairly large minority of prostate cancers, particularly aggressive prostate cancers that have defects in DNA repair, a combination of somatic variants are acquired in the cancer or inherited from the germ via the germline. Over the years, we've actually began to narrow that down into very quite specific groups. So, you know, within that subset, we have a few percent that have mismatch repair defects, and will have really high TMB, and might be vulnerable to immune oncology approaches. And within that subset, we have what we would call homologous recombination repair defects of which BRCA2 is probably the most well known gene there. And what the research has revealed over the years is that the tumours that carry these defects, these HRR mutations, and to some extent, the mismatch repair variants too, they have inherently more aggressive biology. So it sort of doesn't matter where we look in the disease spectrum. We can look early in the localised setting or very late. They tend to be associated with shorter times to progression with shorter overall survival, even with, you know, upstaging in the early setting. And this is partly because you have a defect that is very permissive for the cancers cells to acquire more mutations. So it can more quickly evolve, more quickly generate resistance variants, it's got more diversity. So yeah, it's that aggressive biology we've come to sort of understand to be true in this scenario. And the other thing I would say is that these events happen very early in disease genesis. You know, that's not the same for some of our other variants in prostate cancer. So a BRCA2 mutation, sometimes it's the very first thing that happens in a prostate cancer. So that's really helpful when it comes to testing because we know we can use tumour tissue really early on or we can use a metastatic biopsy if we like. But, you know, it gives you that diversity of source material to test from.

- [Alicia] I think that's so important, and just sort of continuing on that theme of testing, that has really changed a lot in the last few years as well. And I know your work has very much been on the forefront. I remember hearing some of your talks, sharing some of the pitfalls around ctDNA testing and some of the considerations that we have, and the different tissues that we choose, or the blood, or the saliva, or whatever it is that we're using, there are pros and cons to each of these approaches, and innovation is happening in these testing modalities. Can you share what your thoughts are there in terms of the innovation that has occurred, and how you think through getting to the bottom of the HRR status for a given patient when the field around the testing is also changing so rapidly?

- [Alex] Yeah, absolutely. I think when it comes to choosing what material you might test for prostate cancer patient, you're thinking about: Do they have an HRR mutation? Do they have a BCA2 defect? Most commonly, I think we're still going after a tissue source, right? You know, if that's available, I think most guidelines say try to test tissue first. So sometimes that's a metastatic biopsy. Most of the time, it's archival material from the prostate biopsy, diagnostic biopsy often. Now, the challenge with that is it can be quite old. There may not be enough DNA to make the test work, so you can get failure rates and so forth. So it's been really great to have this option of the liquid biopsy now for testing, which I think in many jurisdictions has been around for a few years. I think it's mostly used as a backup. So you don't have tissue available or tissue doesn't work. In a patient that has progressing disease, they can have quite high levels of tumour DNA in their blood, and you can actually use a test to find out whether the cancer carries a BRCA2 or other mutations. So it's been really gratifying coming from that research field to see the uptake of ctDNA testing clinically. So I think that evolution of technology is definitely helping the translation of testing. I think the other thing is at the same time we've become more aware of the nuances in genotyping, you know, an HRR mutation. So we used to think of it very black or white, like you have a mutation, you don't have a mutation. But I think as time goes on, we understand that, well, you have two copies of every gene in the genome. It probably matters if both of those copies are inactivated rather than one. And sometimes mutation is not the only way that a gene can be inactivated. You could have a copy number loss or a whole deletion of the gene, you could have a rearrangement. And I think what's great is we don't necessarily need to know every single nuance of that, but the testing itself is getting more and more comprehensive in its design, so able to capture more of those events, and therefore, you know, that's only gonna help us have more information to direct treatment, you know, in a more precise manner. And I think the final thing I bring up is that we are also having this shift from thinking about the cause of, you know, a kind of certain subtypes. So an HRR mutation is a cause, but the effect of that is that your cancer is deficient in homologous recombination repair. And our targeted therapies can exploit that deficient phenotype. But of course, there are other ways to detect the phenotype than just looking for the original mutation. So, you know, some of the new assays that are coming online are giving us HRD scores, homologous recombination deficiency scores. They're trying to look at signatures from the broader genome that can tell us that our pathway is inactivated, and we don't have to just find that original mutation. So yeah, the innovation is really driving, I guess, a more accurate understanding of who truly has HR deficiency.

- [Alicia] So I'd love to hear a little bit more about that, because that has been influential in the clinic with other solid tumours, but has been a little bit more challenging to pin down when it comes to prostate cancer. And as you said, you know, there are factors beyond the mutations themselves that can cause a phenotype that behaves in a certain way. So I wonder where do you see our understanding of these opportunities and our ability to potentially exploit this weakness in the cancer or error issues in the cancer? Where do you see our opportunities in prostate cancer, and how soon do you see them? Because I'm very much jealous of those other disease settings where they can use loss of heterozygosity, they're using these other ways to identify things. And I just haven't seen that really come to the point of clinical utility yet in prostate cancer.

- [Alex] Yeah, it has been interesting to see that in ovarian and breast, for example, as you stated. I think one of the reasons is that in prostate cancer, there are genes that are very, I would call them bonafide HRR genes, like BRCA2 is one of those core genes, we know it's directly involved in HRR. But we also have these genes that we would sort of say, well, they're within the HRR pathway, they're maybe indirectly involved perhaps in the response to DNA damage rather than the repair, but they, you know, are part of the labels for some of the treatments that we use. And so I think that the phenotype of HRD is not necessarily completely inclusive of the genes that may also drive vulnerability to treatment. So I sort of don't think of it as like a either or. You know, we can either test for HRR mutations or we can test for HRD, I think about these extra pieces of information helping us qualify a decision and better understand, well, what exactly is the biology of this tumour? Because nothing exists in binary levels, right? It's a continuum of maybe increasing vulnerability to a treatment or increasing resistance.

- [Alicia] That's so interesting to think of it more as it just needs to reach a certain threshold, but it is on that continuum and we'll have to continue to learn more. So very, very interesting. Now, another question I wanna ask you, highly, from my perspective, clinically important, is this idea of whether we should think about doing testing along the course of follow up for our patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in particular, because as you alluded to, many of these alterations are going to be present in the primary cancer, but some of them may evolve over time, much less common. What are your thoughts on repeating things like ctDNA or repeat biopsy, and repeat testing? Because I think this is an area where many people have questions and I would say there's still a bit of grey when it comes to clinical practise around repeat testing.

- [Alex] Yeah, absolutely. I think it's a complex question as well, because you have to factor in what's reimbursed or you know, how many times can you feasibly test from a funding point of view, especially outside of the U.S. But then on top of that, yes, there's this question as you mentioned of just what is the cancer changing? You know, if I rely on a tissue result from five years ago, am I missing something in my patient right now? And I think there's a combination of true biological variation, but also technical variation from test to test. And certainly in my experience, some of the times that we see a difference between say, tumour tissue and ctDNA, or tissue tested at very different states, it's actually reflective of maybe a different tumour content in, you know, in one tissue source versus another. And so to give an example, if you did a ctDNA test, but you had only a tiny amount of ctDNA in that sample, you might not actually find some of the variants that are present in that person's cancer. But the reality is you weren't really testing the cancer, it's just your, you know, so it was really an inconclusive test. But our tests at the moment don't do, I would say, the greatest job of discriminating those types of scenarios. So that sort of means that I think there is, at the moment, value in repeat testing, because you've got a better shot at some points in the disease of really capturing the cancer genotype. I hope that as tests continue to improve, we perhaps won't need to do as much testing, and I hope we get to the point where really just one shot at the correct time, will give you a really complete snapshot of DNA repair defect status.

- [Alicia] Great, I'd love to hear your thoughts beyond testing, let's drive a little more into clinical care and how we kind of come to conclusion. Sometimes these tests can be complex, the results can be complex, and some institutions offer multidisciplinary molecular tumour boards where people can have the opportunity to ask questions to really go through things. I think I was talking to someone the other day who said, "Oh, well we have an email address where you can send questions," and I think that's amazing. I wonder, are you able to participate in a multidisciplinary molecular tumour board? What does that look like, and what guidance would you have for groups or practises or institutions who are thinking about whether it's worth putting the investment of time and energy into putting one of those tumour boards together?

- [Alex] Yeah, I mean, I think the importance of multidisciplinary care is only increasing in prostate cancer, and you know, it's not just genetics. Now we have nuclear medicine and other disciplines that didn't used to be so heavily involved. I think the complexity of testing is only gonna continue increasing. I mean, we just talked earlier about, you know, the understanding exactly the allelic state and copy number changes and so forth. So this is only gonna become more complex. And what I would say is that the molecular tumour boards, I agree, are great formal, regular scenarios to have the opportunity to interact with different members of our institutions and so forth, and I would encourage people to set them up when they can. But beyond that, I can say that sitting on the clinical genetics testing side of the fence, many of us are really happy to be engaged and to answer questions. So many of my colleagues email me each week with questions, "Well, what does this test result mean?" And it doesn't even need to be tests from our institution, right, it can be an outside test, "I don't understand what this variable is." And I can speak for the rest of my clinical team, which is that they also would be, or are happy to be part of that conversation, and really want to be involved actually. So I would encourage people to try to find out, well, who are the genetics counsellors that are then acting on this information and make those connections and build those kind of bridges of communication. And yeah, so I think we are actually really keen to be involved. I can give an example actually of, you know, recently we had a test where there was a complex copy number deletion of BRCA2. So it was actually a single exon deletion, and it was reported on the clinical report. But the oncologist who had reached out to me was not familiar with this as an event. You know, what does this mean? Is this the same as a germline mutation? And so just, you know, very quick exchange like that and just clarifying like, "Yes, this will be considered just as actionable as a mutation in BRCA2." You know, it only takes a minute or two to have that discussion, and then the physician is equipped to make a better decision.

- [Alicia] Well, I wish we all had you at our institutions, Alex, that would be amazing. But I think, you know, your point around trying to build the relationships, because the folks on the molecular testing side, on the genetics testing side, have an immense expertise, and also this interest in openness to participate in clinical care. And so if we have access to folks like you, we should build the bridge, because I do think it's worth it, at least it's been worth it in my practise, and I so appreciate that example that you gave. As we start to wind down, I wonder what are your thoughts about the future? What's one key insight you wanna share as you're thinking about where we go with HRR testing and its integration into prostate cancer care?

- [Alex] In terms of sort of a single insight, I mean, that's quite tricky. I think what we are getting better at doing is segmenting the disease even further. So we'll, you know, no longer see, probably as we look to the future, just a single group of patients, but rather a subset of patients defined by the exact type of gene that they have altered or the exact phenotype that their cancer has. So it becomes a, yeah, as we discussed earlier, a sort of continuum, I suppose, of worse DNA repair defects, or certain types of DNA repair defects. And that's gonna fit in really well, I think, with our discussions when we have multiple systemic therapy options available, or what's the best one in this scenario, you know, the more real world data we have as well that shows us how each subgroup benefits or doesn't benefit what degree of benefit they're getting from each therapy will also help those conversations as well. So I'm sure your institution, you're all the time generating somatic information in the context of your patients. So you are able to get this ongoing experience of who is getting the most benefit from each treatment, and probably refine that back into the way that you practise medicine with your patients.

- [Alicia] Well, thank you for saying that, and for giving us so much credit, I think that we often do. But one thing I will say as we do wind down now is that all of these things that you're talking about, all of the progress that we've made, all of the future progress that we will make, is really dependent on us actually ordering the tests in the first place, and actually getting that information. So I think as we consider this, as we integrate these things into our practise, remember when we're sitting in front of the patient to order the test, have those conversations with our genetic testing experts, whether they're genetic counsellors who can help more with the familial side of things, whether they're the molecular testing experts who are helping either on a research perspective or from a clinical care perspective, and there are so many people in between. We are a team and we are doing really important work with these HRR mutations, but we need to order the tests, and that's step one. So thank you so much for talking this through. I sincerely appreciate your expertise, I always do. And I look forward to talking again soon in the future.

- [Alex] Thanks, Alicia, good to chat.

Developed by EPG Health. This content has been developed independently of the sponsor, Pfizer, which has had no editorial input into the content. EPG Health received funding from the sponsor to help provide healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content. This content is intended for healthcare professionals only.