Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Bridging Care

Transcript: Genetic testing in AATD-related liver disease

David Lomas, MD, PhD

All transcripts are created from interview footage and directly reflect the content of the interview at the time. The content is that of the speaker and is not adjusted by Medthority.

Antitrypsin deficiency results from the inheritance of abnormal alleles from both mother and father. The abnormal alleles mean that the protein accumulates in the liver, which means that there is an insufficient protein in the circulation. Most tests for antitrypsin deficiency rely on detecting the deficiency of alpha-1 antitrypsin in a blood sample. Initially, laboratories will look for antitrypsin level, typically by nephelometry, and then having detected a low level of antitrypsin, most labs were then undertaking phenotyping in which the antitrypsin sample is run on a gel, and the position in which the antitrypsin migrates, provides information on the underlying mutation. For example, the normal antitrypsin migrates in the middle of the gel, and is known as M, mutations that run faster than M are named A to L, and those that migrate more slowly are termed N to Z. The common severe Z-deficiency mutation migrates the slowest of all, and hence its name. If we're unable to identify mutation by isoelectric focusing, then we'll revert to DNA sequence analysis, which can identify rare mutations of antitrypsin.

More recently, there has been developed gene panels which will detect the presence either the Z or the S allele in an individual, they are relatively straightforward, but the challenge of those assays is that they may not also detect the rarer alleles. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is typically thought to be a rare disease, but that's not the case. In the North European Caucasian population, about 4% carry the Z-deficiency allele, which means that about 1 in 2,000 individuals are homozygous or have two abnormal copies of the gene. If we move to Mainland Europe, in the Iberian Peninsula, up to 20% of individuals will carry the mild S-deficiency allele. So the most common misconception is this is a rare disease, but in fact, it's quite a common disease, but it's rarely diagnosed. The mutations of alpha-1 antitrypsin cause the protein to misfold and form polymers within the liver.

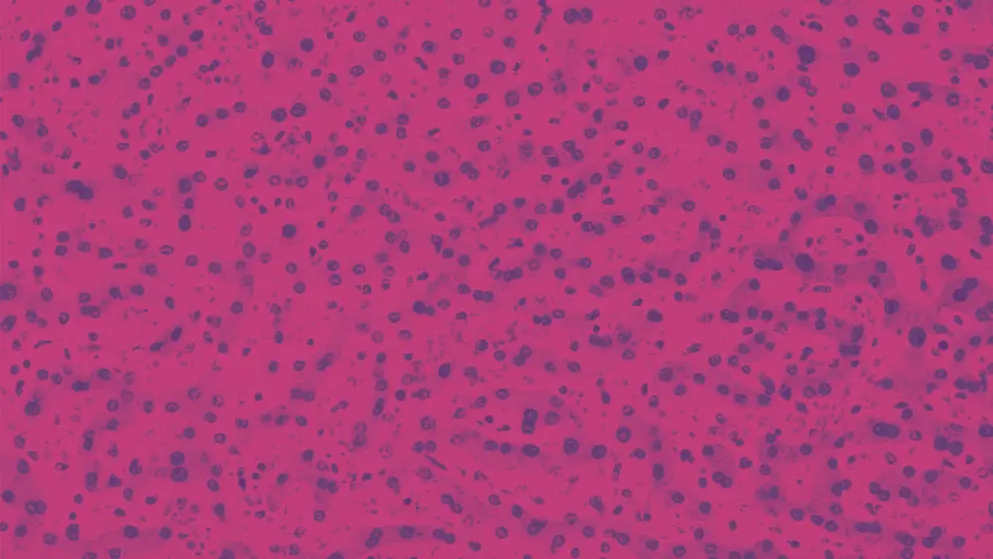

These polymers condense as PAS-positive inclusions within hepatocytes, and that's the cause of the neonatal hepatitis, the cirrhosis, and the hepatocellular carcinoma. The more severe the mutation, the faster the rate of polymerization, the more polymers that accumulate in the liver, and therefore, the greatest risk of liver disease and the more severe plasma deficiency. The severe Z-deficiency allele causes very rapid polymerization of antitrypsin, and hence, accumulation in the liver and liver disease, but this is also seen with other mutations, such as the Mmalton mutation, the Siiyama mutation in Japan, and the King's mutation. In contrast, the S allele or the S mutation causes far slower polymerization, less is retained in the liver and it gives milder deficiency and a lower risk of liver disease. So we can explain the risk of liver disease based on the rate at which the antitrypsin polymerizes and accumulates in the liver. Often a lab will return results such as MM, i.e., two normal copies of the gene, or MS, or MZ, SS, SZ, or other combinations of letters. These letters represent the genes that have been inherited from parents, from mom and dad. Each allele contributes to the production of alpha-1 antitrypsin, 50% comes from one allele, 50% comes from the other. So in an individual who is an MM, we have 100% of alpha-1 antitrypsin. In an SS individual, two copies of the S allele, then the levels of some 60% of normal, in a ZZ individual with two severe deficiency alleles, plasma levels are about 10% of normal, and so the combinations of alleles give predictable effects, for example, an MS will have a normal contribution from the M allele and a reduction of 40% from the S allele, but because that's only half the contribution, the plasma levels are 80%. In an MZ individual, the plasma levels will be 60%, 50% from the M allele, 10% from the Z allele, and in an SS individual, they'll be 60% because both alleles reduce the amount of antitrypsin by 40%. So by looking at the combinations of letters, one can predict the concentration of antitrypsin in the circulation.

Understanding the significance of the letter that return from the lab, allows one to predict the risk of the severity of liver disease, for example, ZZ individuals will have a higher risk of liver disease because more protein will polymerize and accumulate in the liver, far greater risk than the SS's or the SZ's, for example. Typically, once we identify an individual as being a ZZ homozygote, we undertake routine blood tests looking for liver function, we also undertake an ultrasound scan of the liver, looking for evidence of fibrosis, and patients have regular fibroscans looking at liver stiffness in order to identify those that have progressive disease. Because antitrypsin deficiency results in insufficient antitrypsin to protect the lungs, there's an increased risk of emphysema, and so all individuals with antitrypsin deficiency should have regular lung function to assess for evidence of lung damage. Any individual with liver disease should have an assessment of antitrypsin levels or an assessment of antitrypsin genotype. It should be part of the routine workup in all hepatology clinics. In addition, any individual with COPD should also have an assessment for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. I think it's very important that primary and secondary care work together to ensure the timely diagnosis of individuals with antitrypsin deficiency. This typically means looking for the deficiency in any individual who has liver disease or an individual who has COPD.

We also routinely screen brothers and sisters of a ZZ homozygote because if they have the same parents, they're also at risk having the same combinations of alleles and hence, the same risk of having antitrypsin deficiency. We routinely don't screen the children of individuals with antitrypsin deficiency, but we do tell them that their parents have this condition, and if they have any liver disease in the future, they should make the doctor aware that their mother or father are ZZ homozygotes.

Knowing the genetic basis of antitrypsin deficiency, whether you are a Z homozygote, an MZ, and SZ, or other combinations of alleles, allowed us to make a prediction of the likely severity of both liver and lung disease. For example, individuals who carry the Z allele or other rapidly polymerizing mutations, such as, Siiyama, Mmalton, or King's, are likely to have the greatest number of inclusions in the liver and the greatest risk of liver disease. Those individuals are also at risk of having lung disease because they have the severe plasma deficiency. If the individual inherits a rare null allele, that's a gene in which the DNA is truncated or this truncating mutation, then the protein misfolds and is degraded, nothing is retained in the liver and nothing is secreted, these individuals have no increased risk of having liver disease because they're not producing any polymers of antitrypsin, but they still have the risk of having lung disease because they lack an important protease inhibitor in the circulation.

Antitrypsin deficiency is exacerbated by other factors that cause liver disease, for example, the presence of fatty liver or individuals who consume excessive alcohol, and so we routinely advise about good diet, about keeping a healthy BMI, and also about consuming alcohol within recommended guidance. We've routinely follow all individuals up with blood tests to look for evidence of progressive liver disease with fibroscans to look for liver stiffness, and at regular intervals, ultrasound of the liver to look for fibrosis. If there's evidence of liver disease, we obviously see them more regularly to look for the complications of progressive cirrhotic disease and to consider individuals for other therapies such as transplantation. Antitrypsin deficiency is a really exciting condition because at the moment, there are a variety of therapeutic interventions, the sort of likes we've not seen since this condition was first described in 1963.

There are therapies that will manipulate the DNA, therapies that will knock down the RNA that produces antitrypsin, and hence, produces the polymers, therapies that will mutate or revert the messenger RNA from the mutant to the wild-type form, and small molecules that will correct the folding and polymerization of antitrypsin. All of these are currently in clinical trials and are being evaluated. Nevertheless, if the clinical trials are successful, then in the future, it will be essential to know the genotype of an individual, i.e., what precisely is the mutation that underlies the deficiency, because we'll be able to tailor the right therapy to the right genotype, and make sure that patients have the optimum benefit.

Developed by EPG Health. This content has been developed independently of the sponsor, Takeda, which has had no editorial input into the content. EPG Health received funding from the sponsor to help provide healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content. This content is intended for healthcare professionals only.

Updates in your area

of interest

of interest

Articles your peers

are looking at

are looking at

Bookmarks

saved

saved

Days to your

next event

next event