Dermatology

Medical conditions

Alopecia areata

Unmet needs and burden of disease

Dermatitis

Latest news, insights, and guideline updates

Epidermolysis bullosa

Disease information and guideline updates

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Expert congress highlights on disease management

Herpes zoster

Test your knowledge with our quick quiz

Psoriasis

Real-world evidence and patient-centered care

Urticaria

Latest updates and congress highlights

Latest resources

Alopecia areata: Progressing practice

Latest treatment options and patient insights

Expert insights on CSU management

The latest in CSU diagnosis and care

Hidradenitis Suppurativa Learning Zone

Explore updates on diagnosis, epidemiology, disease burden, pathophysiology, and future treatments for HS.

Advances in HS

EHSF 2024: Surgical updates and changes to practice

Alopecia areata webinar

Watch a webinar addressing alopecia areata in skin of color populations, chaired by Antonella Tosti.

Addressing inclusivity in AA assessment

View “Inclusive Care in Alopecia” for an in-depth look at how to better support skin of color populations with alopecia areata.

Roundtable: Biologics in plaque psoriasis

Watch expert roundtable on the use of biologics in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, chaired by Professor Luis Puig.

Browse older resources

Atopic Dermatitis Learning Zone

Welcome to the Atopic Dermatitis Learning Zone, an educational resource, intended for healthcare professionals, that provides credible medical information on the epidemiology, pathophysiology and burden of atopic dermatitis, as well as diagnostic techniques, treatment regimens and guideline recommendations.

Improving Treatment Options for Childhood Psoriasis

This Learning Zone introduces you to our young patient Mia who, along with our paediatric psoriasis experts, helps us to describe the burden of childhood psoriasis for patients and their families, particularly the difficulties around diagnosis, comorbidities and limited treatment options.

Psoriasis Academy

When it comes to psoriasis, a knowledgeable healthcare professional is highly valued by patients (Pariser et al., 2016). With this in mind, we created The Psoriasis Academy, an online hub featuring succinct and easily accessible information for all healthcare professionals who want to know more about psoriasis and keep up to date with the latest developments.

Psoriasis Learning Zone

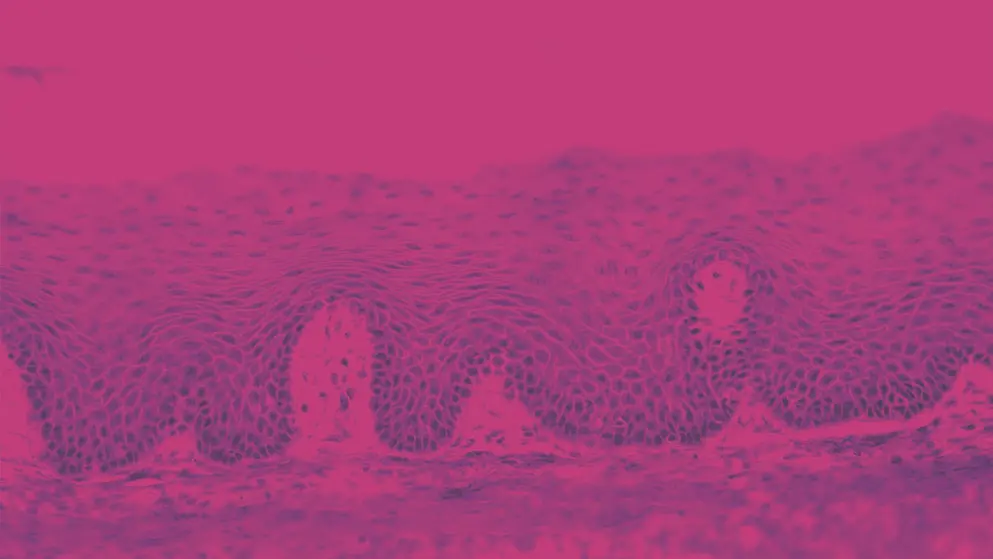

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that often presents with disfiguring, scaling and erythematous plaques of the skin.

Herpes zoster quiz

What are the symptoms, tests, preventative measures and treatments for herpes zoster, more commonly known as shingles? How well do you know this common condition in the elderly? Find out by taking this quiz and learn more with additional content on Medthority.

Childhood psoriasis quiz

What impact does psoriasis have on children’s well-being and how should this condition be managed? Find out with this quiz and learn more about this important topic on Medthority.

of interest

are looking at

saved

next event