Managing CSU

Improve your ability to recognise and manage chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU).

- Explore engaging video content for expert insights into current therapeutic options

- Delve into real-world efficacy data on treatments

- Familiarise yourself with the pathophysiology and symptoms of CSU

- Review national and international guidelines

Developed by EPG Health for Medthority. This content has been developed independently of the sponsor Novartis Pharma AG

Prevalence of CSU

Urticaria is more common than previously thought1

Though there is little epidemiological data for chronic urticaria (CU), a recent meta-analysis reported a point and lifetime prevalence rates of 0.7% and 1.4% respectively1. Interestingly, the results of this study also suggest that CU prevalence is on the rise, though there is substantial variation between geographical regions1.

Overall, chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) accounts for over two-thirds of the cases of CU, and most studies show that it is more common among women than men1,2.

Terminology

Lifetime prevalence is the proportion of a population that at some point in their life (up to the time of the assessment) have experienced the condition3

Figure 1. CSU as a percentage of chronic urticaria cases and the ratio of male to female CSU sufferers (Adapted2,4). CIndU, chronic inducible urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Although all age groups can be affected, the peak incidence is seen between 20 and 40 years of age5. There is no apparent correlation of prevalence with education, income, occupation, place of residence or ethnic background; although prevalence of chronic urticaria has been noted as higher in Asian studies compared with Europe or the USA1. Interestingly, a Korean study published in 2017 also found that CSU had a greater impact on children and the elderly than was expected6.

The majority of patients have no evidence of any exacerbating factor, however a recognised trigger for CSU is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs7.

A population-based study on the epidemiology of CSU in Italy over a 12-year period (2002–2013) demonstrated that the risk of CSU was statistically significantly higher in the presence of the following variables8:

- obesity

- anxiety

- dissociative and somatoform disorders

- malignancies

- use of immunosuppressive drug

- schronic use of systemic corticosteroids

CSU duration

CSU has a duration of at least 1 year in most patients and more than 5 years in a considerable proportion. In very rare cases it can last up to 50 years5,9–12.

Figure 2. The percentage of patients with CSU symptoms at 6 months, 3 years, 5 years, and 25 years after their initial diagnosis (Adapted13).

The evolution of CSU is unpredictable, with spontaneous remissions and relapses7. At least 50% of CSU patients will experience at least one recurrence of CSU symptoms after an apparent resolution14

Prognostic factors for the duration of CSU

The duration of CSU is generally longer in patients with:

- more severe disease5,9

- concurrent angioedema5,9

- concurrent inducible urticaria5,15

- a positive autologous serum skin test (ASST) or autologous plasma skin test (APST)5,16,17

The autologous serum skin test (ASST) is a screening test for autoantibodies in CSU.

Diagnosis is based on a thorough medical history and physical examination as well as diagnostic tests18.

Acute vs. chronic urticaria

While the lifetime prevalence for CSU estimates range from 0.6% to 1.8%19,20, the lifetime prevalence for acute urticaria is thought to be as high as 20%18. Furthermore, acute urticaria accounts for 7–35% of dermatological conditions seen in emergency care21.

Acute urticaria is defined as the occurrence of spontaneous hives, angioedema, or both for <6 weeks18.

Acute urticaria aetiology

The underlying causes of acute urticaria remain idiopathic in 50% of cases, with infections responsible for approximately 40%, and adverse reactions to drugs (9%) and food (1%) responsible for the remaining 10% of cases22.

Managing acute urticaria

For patients with an identifiable trigger, for example a food allergy, patients should be investigated to confirm sensitisation enabling avoidance of the trigger and prevention of future episodes. With acute urticaria being time-limited, treatment is usually focused on symptomatic relief with second-generation H1-antihistamines18. In a study of 100 acute urticaria patients presenting at a French emergency department, 79% of patients treated with levocetirizine were itch free after two days21.

Current guidelines also state that a short course of oral corticosteroids (up to 10 days) may help reduce the duration and activity of acute exacerbations of urticaria18. Interestingly, in the above study, addition of prednisone to levocetirizine treatment did not improve the symptomatic or clinical response compared with levocetirizine plus placebo. This suggests that the addition of a corticosteroid to antihistamine therapy may be unnecessary in acute urticaria patients21.

Sensitisation to insect bites, such as mosquitos, is common and results in immediate hives and pruritic bite papules, although systemic anaphylactic reactions can also occur23. Mosquito-bite hives are a result of antisaliva IgE antibodies and histamine release meaning oral second-generation H1-antihistamines can be an effective option for management of the hives and itch. Placebo-controlled trials have shown cetirizine, ebastine and rupatadine to be effective treatment options in mosquito-bite allergic adult patients. Prophylactically administered rupatadine 10 mg resulted in a 48% decrease in mean hive size and a 21% reduction in itch in these patients. Importantly, for a condition characterised by intense pruritus, rupatadine 10 mg was observed to have a rapid onset of action with a significant reduction versus placebo in hive size and itch reported 15 minutes after administration23. In a separate study, prophylactic cetirizine 10 mg and ebastine 10 mg, but not loratadine 10 mg, resulted in a significant reduction in hive size. While cetirizine had a significantly greater effect on itch than ebastine and loratadine, it also increased the levels of sedation observed, although the clinical significance was uncertain as no patients dropped out23.

Burden of disease

The impact on patients’ lives goes beyond effects on skin; currently treated patients experience higher levels of health-related impairment in their functioning in work and non-work activities and quality of life and are more frequent users of healthcare than similar individuals without the condition24

Quality of life

CSU adversely affects many aspects of patients’ lives5

Figure 3. The impacts of CSU on quality of life (Adapted25,26).

Many aspects of quality of life (QoL) are found to be reduced in patients with CSU27 and the presence of angioedema further impairs QoL scores28. The QoL of patients with CSU is at least as impaired as in patients with other skin diseases, with higher impact on daily living and physical discomfort29.

Measurement of patient QoL

QoL in CSU patients may be measured using specific skin disease questionnaires such as the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DQLI)30,31

Factors contributing to a reduced QoL

In addition to the classical symptoms associated with CSU, factors of major importance to patients that contribute to a reduced QoL include11:

- unpredictability of attacks

- persistent lack of sleep

- fatigue

- disfigurement

Patients with CSU also often have comorbidities such as depression and anxiety32. Over 60% of CSU patients report anxiety at some point during their flares11 and 17% are diagnosed with depressive or somatoform disorders33.

Disease that is refractory to antihistamines is also potentially a much larger problem than previously believed. In 2019, 1-year data from the AWARE study was published34. This suggested that antihistamine-refractory patients demonstrate high levels of uncontrolled disease, angioedema and co-morbid chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU). They were noted to have impaired QoL, be generally undertreated, and are increasingly dependent on healthcare services35,36; most patients did not receive guideline-recommended treatments35. The Scandinavian arm of the AWARE study noted high rates of healthcare utilisation and QoL impairment37.

The RELEASE survey study in Japan evaluated real world QoL impairment, reporting similar findings to the AWARE study. Findings suggest that patients with worse urticaria have greater work productivity loss and activity impairment compared with milder cases, and report greater dissatisfaction with their health and treatment38.

Visit Industry-Sponsored AWARE study eLearning module

The socioeconomic burden

The socioeconomic cost of CSU is high in terms of direct medical costs and indirect costs, such as lost wages because of absences from work5,39. It is estimated that approximately 60–70% of patients report absence from work or school as a direct result of their CSU11,39 and 26% report that it causes three or more days’ absence a year39. Patients with severe CSU incur higher direct and indirect costs than patients with mild or moderate disease. Most patients, particularly those with angioedema, will need continuous medication to alleviate symptoms and regular visits to healthcare facilities5,39.

Almost three-quarters of patients with moderate to severe CSU attend a healthcare professional at least once per year (mean of 3.3); consultant allergists (39.0%) and dermatologists (38.5%) are the most common specialties visited40.

In addition, CSU is heterogeneous in its regional management, with healthcare utilisation and outcomes differing between healthcare systems. However, there is still a high overall unmet need in CSU patients associated with healthcare resources use, and a large negative effect on QoL and work productivity41.

CSU pathophysiology

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is driven by the activation of mast cells, which release histamines and other immune modulators, although the precise mechanism is not fully known42.

Mast cell activation in CSU

Urticaria is a mast-cell-driven disease18.

Figure 4. Interactions of mast cells on urticaria symptoms (Adapted43,44).

Though the pathophysiology of urticaria is complex and yet to be fully characterised, it is thought that activated mast cells release histamine and other inflammatory mediators, such as platelet-activating factor (PAF) and cytokines45. The mediators cause sensory nerve activation, vasodilatation, and plasma extravasation as well as cell recruitment to urticarial lesions, and form the basis for antihistamines being first-line management12,46,47.

CSU skin lesions show recruitment of mast cells, basophils, neutrophils, eosinophils and T-lymphocytes18,48–52.

Figure 5. The recruitment of mast cells, basophils, neutrophils, eosinophils and T-lymphocytes in CSU skin lesions (Adapted18,48–52).

The mast cell activating signals in urticaria are ill-defined and likely to be heterogeneous and diverse18.

Basophils

Basophils, along with mast cells, play an important role in the pathophysiology of CSU. Peripheral blood basophils from CSU patients have unique features that reverse upon remission and in response to therapy7,53:

- basopaenia is typically found in CSU patients

- basophils from CSU patients also tend be less responsive to stimuli that act through the IgE receptor

- basophils from CSU patients are hyperresponsive when stimulated with other sera regardless of source

Immunoglobulin E

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) is key to the release of histamine and other pro-inflammatory mediators from mast cells and basophils and may play a role in the pathogenesis of CSU18.

IgE binds to high-affinity (FcεRI) receptors on mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, alveolar macrophages and antigen-presenting cells54–56. Cross-linking of IgE bound to FcεRI receptors triggers degranulation and release of inflammatory mediators55–57. There is a strong association between IgE and allergic conditions57.

The FcεRI receptor on mast cells plays a key role in activation of these cells and in the pathophysiology of CSU58,59.

Figure 6. IgE interactions with mast cells in CSU (Adapted42,60–62). IgE, immunoglobulin E; PAF, platelet-activating factor.

Mast cell activation may either be via autoimmune, allergic or idiopathic mechanisms61–64. It is generally believed that allergy is not an underlying cause of CSU, although total IgE levels are typically higher in CSU patients than in healthy individuals62,65.

CSU Pathogenesis

A summary of the current understanding of the pathogenesis of CSU is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Pathogenesis of CSU summary. CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IgG, immunoglobulin G; PAF, platelet-activating factor; TPO, thyroid peroxidase (Adapted64,66,67).

Potential role of histamine intolerance in CSU

It has been suggested that chronic infections, autoreactivity and intolerance to food may play a role in CSU. The type of food intolerance described differs from regular IgE-mediated food allergy as it involves a pseudoallergenic response to artificial additives, natural compounds and dietary histamines. A study was conducted by Siebenhaar et al. in 2016 with the aim of determining the rate that this histamine intolerance was evident in patients with CSU68.

It was noted that from history alone it was impossible to determine whether a pseudoallergen-free diet would help the symptoms of CSU sufferers, however, avoidance diets did improve the symptoms of some urticaria sufferers. However, it was reported that histamine intolerance was a rare comorbidity68.

CSU symptoms

The symptoms of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) include itchy hives (wheals) and angioedema18

The symptoms of CSU may appear without warning with a variable intensity5,18 and may profoundly impact patients' day-to-day lives5,27,32,69,70. In CSU, itchy hives, angioedema or both, may occur spontaneously every day, or almost daily for six weeks or more18.

Hives

A hive consists of three typical features18:

- Central swelling of variable size, usually surrounded by a reflex erythema (Figure 8)

- Associated itching (pruritus), or sometimes a burning sensation

- Transient nature, usually resolving within 30 minutes to 24 hours

Figure 8. Hives are superficial swellings with pale centres surrounded by a red flare71 .

Terminology

The terms ‘itch’ and ‘pruritus’ are interchangeable, as are ‘hive’ and ‘wheal’

Reflex erythema describes the redness of the skin due to dilated capillaries that is triggered by local neural reflexes. Erythema typically blanches with pressure

Angioedema

Angioedema (deep tissue swelling) is typically characterised by18:

- sudden, pronounced swelling or redness of the lower dermis and subcutis or mucous membranes (hypodermis or superficial fascia)

- sometimes pain rather than itching

- up to 72 hours for resolution

The eyelids and lips are most commonly affected, while the tongue, extremities, genitalia, oral cavity mucosa and upper respiratory tract may also be affected72.

Figure 9. Percentage of CSU patients with angioedema alone, hives or both (Adapted73).

Relationship between CSU symptoms and quality of life

In CSU, changes in symptom severity are closely linked to changes in health-related quality of life (HRQoL). If an improvement (or worsening) in signs and symptoms is found, it is highly likely that an improvement (or worsening) HRQoL is also experienced74

CSU diagnosis and assessment

Since there is no definitive test for chronic spontaneous urticaria, diagnosis is based on a thorough medical history and physical examination as well as diagnostic tests18.

The importance of earlier diagnosis of CSU

Despite the clear diagnostic algorithm included in international guidelines, evidence suggests that many patients with CSU experience delays in receiving a diagnosis18,40,75,76

The Assessment of the Economic and Humanistic Burden of Chronic Spontaneous/Idiopathic Urticaria Patients (ASSURE-CSU) aimed to provide real-world evidence on the unmet needs of patients with uncontrolled CSU by assessing various aspects of the patient experience. Among the 673 patients included in the study, the mean disease duration was 4.8 years, and the mean (SD) duration of disease from symptom onset to diagnosis was 24.0 (63.36) months, with a median delay of 4.7 months. The authors attributed this delay in diagnosis and specialist referral to a lack of specialist knowledge in the primary and secondary care settings with regard to CSU40.

For patients, these delays in obtaining a diagnosis represent a source of great frustration. Many of them will visit multiple healthcare providers before their diagnosis is confirmed and appropriate treatment is initiated75. For example, in an Italian study published in 2017, three-quarters of the 190 patients included visited ≥3 different physicians before finally receiving a diagnosis of CSU76. Other studies have shown that during this process, patients frequently resort to online resources in search of answers75. This may result in inaccurate self-diagnoses and, alarmingly, attempts to self-medicate are not uncommon. There have even been reports of patients using unprescribed prednisone in a bid to alleviate their symptoms75.

Of the patients included in the Italian study described above, 57% expressed hope for a more rapid and straightforward treatment process, particularly in terms of diagnosis76. Better education for both patients and physicians to help raise awareness of CSU could help spare patients the frustration and anxiety associated with delayed diagnosis and facilitate earlier interventions with appropriate therapeutic agents75.

Find out more about the journey to diagnosis from the patient perspective with our podcast, “All Things Urticaria: The Patient Voice”.

CSU diagnosis

Awareness and understanding of CSU are important to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment or referral18. Guidelines for diagnosis recommend a thorough patient history and physical examination followed by routine diagnostic tests18,77. Extended diagnostic tests may be needed, based on patient history, to exclude differential diagnoses.

The 2017 International EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines recommend a three-step process for the effective diagnosis of urticaria (Figure 10)18.

Figure 10. The three steps recommended in the 2017 International EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines for the effective diagnosis of urticaria (Adapted18). EAACI, European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; EDF, European Dermatology Forum; GA2LEN, Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; WAO, World Allergy Organization.

Patient history in CSU

Step 1

The first step in the diagnosis of urticaria should be to take a thorough patient history18

Recommended questions should take into consideration a number of different factors including18,77:

- duration of disease

- physical symptoms

- provoking factors

- family history

- impact on everyday life

- previous diagnostic tests/therapy

Duration of disease

- Time of onset

- Frequency/duration and provoking factors for hives

- Diurnal variation

- Occurrence in relation to weekends, holidays and/or foreign travel

Physical symptoms of CSU

- Shape, size and distribution of hives

- Associated angioedema

- Associated symptoms (e.g. bone/joint pain, fever abdominal pain)

See also Assessment Tools for disease activity and impact in CSU

CSU provoking factors

- Induction by physical agents or exercise

- Observed correlation to food

Family history in CSU

- Family and personal history regarding wheals and angioedema

- Previous or current allergies

- Gastric/intestinal problems

- Association with infections

- Use of alternative therapeutic drugs (e.g. nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], angiotensin-converting-enzyme [ACE]-inhibitors)

- Relationship to the menstrual cycle

- Smoking habits (especially use of perfumed tobacco products or cannabis)

- Type of work, hobbies

- Stress (eustress and distress)

- Occurrence in relation to travel

Impact of CSU on everyday life

- Quality of life (QoL) related to urticaria and emotional impact

See also Assessment Tools for disease activity and impact in CSU

Previous diagnostic tests/therapy in CSU

- Previous therapy and response to therapy

- Previous diagnostic procedures/results

Figure 11. Examples of the type of questions that may be asked when taking a clinical history (Adapted77). ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Physical examination in CSU

Step 2

The second step in the diagnosis of urticaria should be to conduct a physical examination18

Physical examination should include:

- identification and characterisation of any current lesions

- diagnostic provocation tests if indicated if chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU) is suspected

- checking for signs of systemic illness

Table 1. Diagnostic provocation tests for CIndU (Adapted78).

Diagnostic tests for CSU

Step 3

As a third step, diagnostic tests should be performed as appropriate18

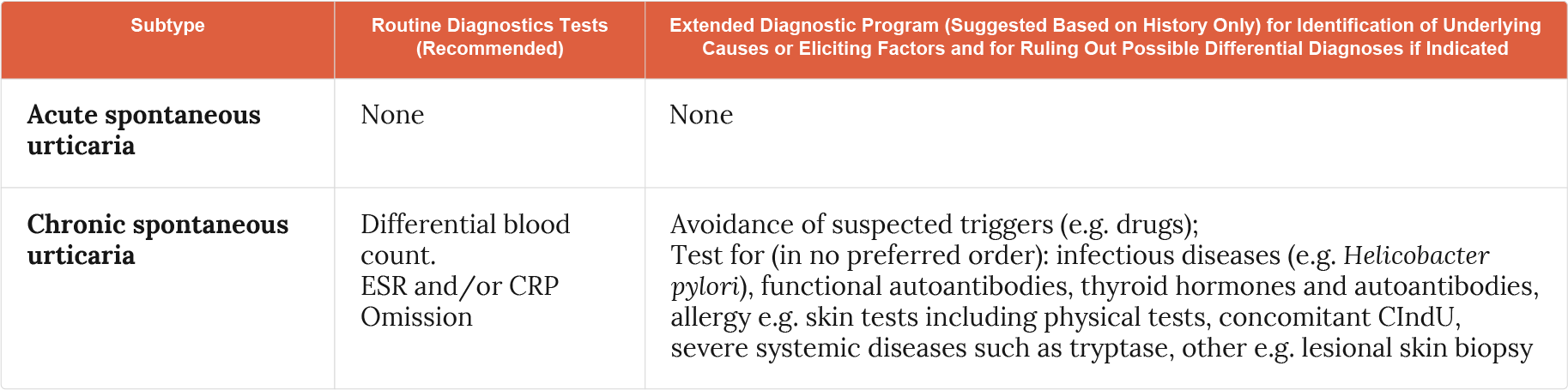

Routine diagnostic tests

Only very limited routine diagnostic tests should be performed in CSU and these tests should not be performed in acute urticaria18.

Figure 12. Routine diagnostic tests in CSU (Adapted18). CRP, C-reactive protein; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Extended diagnostic tests

Extended diagnostic tests may be needed, based on patient history, to exclude differential diagnoses18.

Extended diagnostic tests may be considered where directed by patient history, for identification of underlying causes and for ruling out possible differential diagnoses if indicated (Figure 13). Unless strongly indicated by patient history (e.g., allergy) extended diagnostic tests should not be carried out in acute spontaneous urticaria18.

Figure 13. Extended diagnostic tests in CSU (Adapted18). ASST, autologous serum skin test; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Infectious diseases

- Bacterial, viral, parasitic or fungal infections have been implicated as underlying causes of CSU79

- e.g., H. pylori, Streptococci, Staphylococci, Versinia, Giardia lamblia, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Hepatitis virus, Norovirus, Parvovirus B19, Anisakis simplex, Entamoeba, Blastocystis

- The frequency and relevance of infectious diseases varies between different patient groups and geographical regions18,79

- More research is needed to make definitive recommendations regarding the role of infection in urticaria18,79

Type I allergy or pseudo-allergic reactions

- Type I allergy is a rare cause of CSU in patients who present with daily or almost daily symptoms, but may be considered in CSU patients with intermittent symptoms79,80

- Pseudo-allergic (non-allergic hypersensitivity) reactions to NSAIDs, food, or food additives may be more relevant for CSU with daily symptoms79

- Diagnosis should be based on an easy-to-follow diet protocol79

The autologous serum skin test (ASST)

A positive ASST is indicative of CSU42,81. The presence of autoantibodies can aid in the diagnosis of CSU. The ASST is the only test available to screen for autoantibodies in CSU, against either immunoglobulin E (IgE) or high-affinity (FcεRI) receptors81. Confirmation of functional autoantibodies requires a Basophil Histamine Release Assay (BHRA)81,82.

The ASST:

- assesses autoreactivity in response to serum collected during active disease77

- evaluates the presence of histamine-releasing factors (including autoantibodies)42,81

A positive ASST response is defined by an inflammatory red wheal response81.

Lesional skin biopsy

- If urticarial vasculitis is suspected, biopsy of lesional skin should be carried out18

- Damage of the small vessels in the papillary and reticular dermis and/or fibrinoid deposits in perivascular and interstitial locations are suggestive of UV (urticarial vasculitis)18

Differential diagnosis

Recurrent hives and angioedema may occur in various different diseases (Figure 14), so excluding differential diagnoses is an important aspect of the diagnostic work up for CSU18.

Figure 14. Differential diagnoses for patients with hives and angioedema (Adapted18). AAE, acquired angioedema; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; AID, acquired autoinflammatory disorders; HAE, hereditary angioedema; IgD, hyperimmunoglobulinemia D; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Recommended diagnostic algorithm for urticaria

Figure 15. Diagnostic algorithm for CSU (Adapted18). AAE, acquired angioedema; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; AE, angioedema; AID, acquired autoinflammatory disorders; HAE, hereditary angioedema.

Assessment tools

Assessment tools for disease activity and impact in CSU

International urticaria guidelines recommend the use of tools in CSU patients to measure and monitor disease activity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)18. Physicians have a choice of tools (generic or CSU specific) to assess the severity impact of CSU and treatment response. In CSU, changes in symptom severity are closely linked to changes in HRQoL74.

Table 2. Disease activity and impact tools (Adapted10,18,30,83–85).

| Measurement | Hives and Itch | Angioedema |

| Disease activity | · Urticaria Activity Score (UAS) · Weekly Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) |

· Angioedema Activity Score (AAS) |

| Urticaria-specific QoL | · Chronic Urticaria · Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) |

· Angioedema · Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL) |

| Dermatology-specific QoL | · Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) | |

| Disease activity, disease-specific QoL and treatment effectiveness | · Urticaria Control Test (UCT) | |

The Urticaria Activity Score (UAS)

The UAS is a validated daily measure, encompassing hives and itch, to assess urticaria severity and monitor treatment outcomes (Table 3)18,31.

Table 3. Urticaria activity score (Adapted18). ISS, Itch Severity Score.

The daily UAS (range, 0–6) equals the sum of daily Itch Severity Score (ISS) and the hives score18,86.

The UAS7 (range, 0–42) is a weekly composite of the daily UAS (Figure 16)86.

Figure 16. Calculating the UAS7 (Adapted18,86). UAS7, 7-day Urticaria Activity Score.

UAS7 is a measure of CSU severity over 7 days5,18 (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Interpreting the UAS7 (Adapted18,84). UAS7, 7-day Urticaria Activity Score.

A variation of the UAS7, the UAS7TD was assessed to determine whether the UAS7 could be used to divide patients into subgroups to better assess impact on quality of life87. It was found that categorical UAS7 subgroups could be used to predict differences among patients with different levels of disease severity – this may enable better clinical monitoring of treatment efficacy87.

The Angioedema Activity Score (AAS)

The AAS is used to assess disease activity in patients with recurrent angioedema18.

The AAS allows the patient to score each of five key factors relating to their symptoms from 0 to 3 (giving a daily score of 0–15). Daily AAS can be summed to give 7-day scores (AAS7), 4-week scores (AAS28), and 12-week scores (AAS84)88.

The Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL)

The CU-Q2oL patient questionnaire was designed and validated for the assessment of QoL specifically in chronic urticaria, including the physical, psychosocial and practical aspects of this condition89. It consists of 23 questions covering six key domains relevant to89:

- pruritus

- swelling

- impact on life activities

- sleep problems

- looks

The effects of disease on each domain are scored from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) and totalled to give an overall score ranging from 0–92 with higher scores indicating a greater impairment in QoL. The CU-Q2oL is simple to administer and requires approximately five minutes to complete89.

The Angioedema Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL)

The AE-QoL is the first angioedema-specific patient-reported QoL questionnaire. It consists of 17 questions across 4 domains (Figure 18)85.

Figure 18. AE-QoL Questionnaire Domains (Adapted85).

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)

DLQI is a validated and widely used dermatology-specific patient questionnaire for evaluating HR-QoL in patients with a variety of skin conditions including CSU30,31. It is used in clinical practice and trials but was not included in the last international urticaria guidelines18.

The Urticaria Control Test (UCT)

The UCT is a single questionnaire comprised of four questions designed to evaluate the physical symptoms of chronic urticaria (itch, hives and/or angioedema), the impact on HR-QoL and the effectiveness of treatment over four weeks85. It consists of just four simple questions allowing rapid and easy completion and is valid for both CSU and CIndU85,90.

Fast facts

Understanding Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria (CSU) and its impact is crucial to optimise treatment outcomes. Here are some key points to help better understand this debilitating skin condition18,33,69,83,89,91–93:

Comorbidities in CSU

Unfortunately for many patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), the itchy hives and/or angioedema associated with the condition is not all they have to contend with. A substantial number of patients also experience comorbidities associated with the development of CSU94.

Autoimmune diseases in CSU

The pathogenesis of CSU in a subset of patients is believed to be a consequence of an autoimmune response driven by immunoglobulin E (IgE) or immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies94,95, and a strong association is found between CSU and major autoimmune diseases96, with evidence suggesting potential autoimmune aetiology in up to 50% of CSU patients42. Patients with CSU, therefore, are thought to be at an increased risk of developing other autoimmune disorders. In fact, while the global prevalence of autoimmune diseases is considered to be ≤1%, in patients with CSU it is thought to be ≥1%94,95.

Evidence suggests a potential autoimmune aetiology in up to 50% of patients with CSU42

A large Israeli population study exploring the links between CSU and other autoimmune conditions found that a diagnosis of CU was associated with an increased risk of developing hypothyroidism (9.8% vs. 0.6%; p<0.0005) and hyperthyroidism (2.6% vs. 0.09%; p<0.0005). Interestingly, the presence of autoimmune disease was significantly higher in female patients than male patients. A similar effect was seen with type 1 diabetes (female patients OR, 12.92; 95% CI, 6.53–25.53; p<0.0005 vs. male patients OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.15–4.73; p=0.01). Importantly, the onset of type 1 diabetes was observed in the majority (84.8%) of patients in the years after receiving a diagnosis of CU. Meanwhile, a number of autoimmune conditions were only significantly increased in female patients. These included rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 19.88; 95% CI, 10.15–38.92; p<0.0005), Sjögen syndrome (OR, 23.30; 95% CI, 7.31–74.20; p<0.0005), coeliac disease (OR, 57.83; 95% CI, 7.99–418.29; p<0.0005) and systemic lupus erythematosus (OR, 26.71; 95% CI, 6.49–109.90; p<0.0005)96.

More recently, a Korean study utilised their national database to explore the presence of various conditions in patients with CU, patients with CSU and patients without CU/CSU. Similar to Confino-Cohen et al., Korean patients with CU (12.34%) or CSU (11.34%) had a significantly increased rate of autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITD) compared to controls (5.49%)6.

Alopecia areata (AA) is another autoimmune disease with a global prevalence of 0.1–0.2%. However, this differs between populations and studies with an observed prevalence of ~0.7–3% in the USA, and ~2% in the UK. An Israeli study matched 1,751 patients with AA to 3,502 control patients and assessed their respective comorbidities. Interestingly, patients with AA had a significantly increased risk of having comorbid CSU (OR, 6.15; 95% CI, 4.06–9.32; p<0.001) than the control group. Furthermore, patients with both AA and CSU were more likely to also have comorbid allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis than patients with CSU but not AA in the control group97.

To gain greater clarity on the association of AITD and CSU, a systematic literature review compared data from 169 identified publications. A strong correlation was seen between CSU and elevated IgG antithyroid autoantibodies, in particular IgG-anti-TPO antibodies. Furthermore, some evidence suggests that patients with CSU typically have higher levels of IgE-anti-TPO autoantibodies than controls. As expected, these changes in autoantibody levels are also associated with elevated rates of AITD. It was identified that patients with CSU are more likely to experience hypothyroidism and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis than hyperthyroidism and Grave’s disease. In addition, and supporting the Israeli population study, thyroid dysfunction was more commonly observed in female than male patients with CSU94,96.

A separate systematic literature review looked at the published rates of a broader spectrum of autoimmune diseases in patients with CSU. The rates of comorbidity in the majority of studies were ≥1% for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and coeliac disease, ≥2% for Grave’s disease, ≥3% for vitiligo and ≥5% for pernicious anaemia and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis95.

To find out more about autoimmune comorbidities in CSU, check out our All Things Urticaria podcast episode ‘Let’s talk comorbidities’ with Professor Marcus Maurer and Dr Simon Francis Thomsen.

Allergic disease

While a link between chronic urticaria and atopic diseases has been suggested, until recently the epidemiological data was lacking98, but some data are starting to clarify the situation. Among a Korean population of patients with CU or CSU, the likelihood or having comorbid allergic rhinitis, drug or other allergies, or asthma was approximately 4.68 times higher than in the control group (Table 4)6.

Table 4. Mean percentage of patients diagnosed with comorbidity between 2010 and 2013 in Korea (Adapted6).CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; CU, chronic urticaria.

In an Israeli population study, 11,271 patients with CU were compared to 67,216 age- and sex-matched controls98. Interestingly, while fewer people experienced allergic comorbidities than observed in the Korean study, they were still significantly more common in patients with CU than in the control group. In this setting, 10.8%, 9.8% and 19.9% of patients with CU had been diagnosed with asthma, atopic dermatitis or allergic rhinitis, respectively compared to 6.5%, 3.7% and 10.1% of patients in the control group98. A multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status and ethnicity revealed that CU was significantly associated allergic rhinitis (OR, 2.03; p<0.001), atopic dermatitis (OR, 2.77; p<0.001) and asthma (OR, 1.62; p<0.001)98. Meanwhile, a comparison of elderly (>60 years of age) and non-elderly patients with CU in Korea revealed that elderly patients with CU were significantly more likely to have comorbid atopic dermatitis than non-elderly patients (37.8% vs. 21.7%, p=0.022)99. However, no difference was seen in the prevalence of asthma or allergic rhinitis99.

The role of allergies and mast cells in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has gained increased attention recently. With this possible pathophysiological similarity between IBS and CU, Shalom et al. produced a follow-up study addressing the epidemiological links between the two conditions in Israel98. A total of 1.7% of patients with CU had concomitant IBS versus 0.8% of controls (p<0.001) giving an OR of 1.86 (95% CI, 1.57–2.19; p<0.001). While a pathophysiological explanation remains hypothetical, this study does suggest an association between IBS and CU, warranting further investigation98.

Psychiatric conditions in CSU

Dermatological conditions can have a substantial impact on the mental wellbeing of patients. A UK study reported that 17% of dermatology patients required psychological support while 85% reported that the psychosocial aspects of their skin condition are a major component of their illness100. More recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis including a total of 25 studies revealed that nearly one third of patients with chronic urticaria have one or more psychiatric comorbidity101.

It has been reported that nearly one third of patients with CU have at least one underlying psychiatric comorbidity101

The psychological burden of CSU is significant. In a survey of 369 patients with CSU, the prevalence of psychological issues was roughly twice as high as reported by matched controls (Figure 19)24.

Figure 19. Prevalence of mental health comorbidities and sleep difficulties among patients with CSU and matched controls (Adapted24). CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Similar results were reported in a German study of 100 patients with CSU who were screened for mental health comorbidities. Among this group of patients, 48% had one or more mental health disorder with the most common being anxiety (30%) and depressive and somatoform disorders (17% each)33.

The psychological comorbidities associated with CSU have been shown to extend beyond anxiety and depression. Patients with CSU also have higher levels of alexithymia (the inability to identify and communicate emotions) than healthy controls and may be related to a link between pruritus severity and state anger as assessed by the State-Trait Anger Inventory (STAXI)102. Furthermore, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been associated with CSU with 34% of patients with CSU in one study meeting the diagnostic criteria for PTSD vs. 18% of allergy control patients103–105.

The impact of these associated comorbidities should not be underestimated. In a study of 746 patients with CU and 5,107 patients with psoriasis, patients with CU had a comparable impairment of mental/physical health to those patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (Figure 20)106.

Figure 20. Psychological burden of CU and psoriasis (Adapted106). CU, chronic urticaria.

To find out more about psychiatric comorbidities in CSU, check out our All Things Urticaria podcast episode ‘Let’s talk comorbidities’ with Professor Marcus Maurer and Dr Simon Francis Thomsen.

The Aim of Treatment

The aim of treatment for urticaria is quick and complete symptom control5,18,107

The recommended treatment algorithm

The 2017 European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI)/Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN)/European Dermatology Forum (EDF)/World Allergy Organization (WAO) guidelines recommend the following step-wise approach to the treatment of urticaria (Figure 21)18.

Figure 21. The 2017 EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO recommended treatment algorithm for chronic urticaria (Adapted18). EAACI, European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; EDF, European Dermatology Forum; GA2LEN, Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; WAO, World Allergy Organisation.

A number of additional treatment options are mentioned in the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines but are not included in the recommended treatment algorithm due to limited supporting evidence18.

It is recommended to reassess the need for continued or alternative drug treatment every three to six months, as the severity and symptoms of urticaria may fluctuate and spontaneous remission may occur at any time18.

An urticaria treatment algorithm should serve both patients with easy-to-treat symptoms and those more refractory to treatment and should allow the stepping up or stepping down of treatment depending on requirements over time108.

First-line therapy for CSU

International EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines recommend the use of second generation H1-antihistamines, at licensed doses, as first-line treatment for CSU18.

2017 updates to the international CSU guidelines

First generation H1-antihistamines are no longer recommended for the treatment of urticaria due to5,109,110:

- pronounced central nervous system (CNS) and anticholinergic effects/interference with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (sedating effects)

- drug interactions, particularly with drugs affecting the CNS, e.g., analgesics, hypnotics, sedatives, mood elevating drugs and alcohol

Figure 22. Potential adverse effects of first (old)-generation H1-antihistamines (Adapted111). CNS, central nervous system.

Second generation H1-antihistamines are well tolerated by most patients and are non-sedating or minimally sedating, and free from anticholinergic effects18. However, astemizole and terfenadine, two of the earlier modern second-generation drugs, require hepatic metabolism for full activation and have cardiotoxic effects if this metabolism is blocked18. Due to these safety concerns, these two drugs are no longer available in most countries, and are not recommended in the CSU guidelines18. Despite this setback, newer modern second-generation antihistamines were developed to overcome these issues. Initially, the new generation of antihistamines comprised cetirizine (metabolite of hydroxyzine), loratadine, and fexofenadine but now includes acrivastine, azelastine, bepotastine, bilastine, desloratadine, ebastine, epinastine, levocetirizine, mequitanzine, mizolastine, olopatadine, and rupatadine18.

While a total of 16 different second generation H1-antihistamines have featured in review articles and clinical studies focussed on the treatment of CSU, only 10 are widely recognised in current guidelines (acrivastine, bilastine, cetirizine/levocetirizine, ebastine, fexofenadine, loratadine/desloratadine, mizolastine, and rupatadine)112.

Why not combine first- and second-generation H1-antihistamines?

While second-generation antihistamines are the recommended first-line therapy in CSU, many physicians continue to believe that the addition of a sedating, first-generation antihistamine in the evening can aid patient sleep. However, the results from a randomised, double-blind, cross-over study indicated that the addition of hydroxyzine to a second-generation antihistamine did not improve patient sleep, but did increase daytime somnolence, supporting the use of second-generation antihistamines only in the treatment of CSU110,113.

Clinical evidence

Several second-generation H1-antihistamines are used for the management of CSU. Here we review the available clinical data in adults for each.

Bilastine

Bilastine is a second-generation H1-antihistamine that is used for the management of allergic rhinitis and urticaria. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of 20 mg bilastine versus 5 mg levocetirizine and placebo in adult patients with CSU114. Over a 4-week period, 525 patients were assessed with total symptom scores used as the primary endpoint. From day 2 onwards, bilastine showed a significant improvement in the patients’ symptoms compared with placebo. Furthermore, bilastine treatment also resulted in significant improvements compared with placebo in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores, as well urticaria-associated discomfort, and sleep disruption. When considering the levocetirizine group, bilastine was observed to have comparable efficacy and tolerability114. A Japanese study has indicated that the efficacy and tolerability of bilastine is maintained over the course of a year115.

Cetirizine

Clinical data on the efficacy and safety of cetirizine in patients with CSU has been available for 30 years. In 1988, 30 patients with CSU were treated with 10 mg cetirizine or placebo in a double-blind cross-over trial116. This early data indicated that cetirizine significantly reduced the occurrence of hives and pruritus compared with placebo (p<0.001). Of the 30 patients, 26 improved on cetirizine, two on placebo and two discontinued cetirizine due to a lack of efficacy. Meanwhile, mild sedation was observed in two patients receiving cetirizine and one patient given placebo116.

Head-to-head

Cetirizine has also been evaluated in CSU in several head-to-head trials. An early study compared cetirizine with the first-generation antihistamine hydroxyzine and placebo117. While cetirizine was shown to have similar efficacy to hydroxyzine, it had a lower incidence of somnolence and showed levels not significantly different to those observed in the placebo group117.

More recently, the effectiveness and safety of cetirizine was compared to that of rupatadine. In a randomised, double-blind, 6-week trial, 70 patients with CSU were treated with 10 mg of cetirizine or rupatadine once daily118. Evaluations of the mean number of hives (wheals), mean pruritus score and mean total symptom score revealed significantly greater improvements with rupatadine than cetirizine (Figure 23)118.

Figure 23. Mean change from baseline in mean total symptom score (MTSS), mean number of wheals (MNW) and mean pruritus score (MPS) following 6 weeks of treatment with cetirizine (n=31) or rupatadine (n=33) (Adapted118).

The study also used a visual analogue scale (VAS) to assess sedation with participants asked to score themselves on a scale from 0 (alert) to 100 (very sleepy). After six weeks, cetirizine was shown to produce a significant increase in the patients self-reported sedation compared with baseline (p=0.0004). Rupatadine did not induce a significant change in sedation levels after 6 weeks compared with baseline (p=0.2179)118.

Desloratadine

Since 2001, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of desloratadine in patients with CSU have shown that once-daily dosing (5 mg) offers significant symptom improvements versus placebo. Furthermore, the adverse event profile, including somnolence, was similar between the desloratadine and placebo groups119–121. Desloratadine has also been shown to improve the quality of life of patients with CSU. Using the DLQI, 77% of patients had a clinically significant improvement in the DLQI score after 42 days of treatment122. Interestingly, a third of patients in the study experienced complete symptom relief whereas 10% received no benefit from desloratadine treatment highlighting the heterogeneity in patient response to antihistamine treatment122.

Further studies have investigated whether desloratadine can be prescribed on an as-needed basis rather than continuously123,124. Patients taking daily desloratadine had significant improvements in quality of life compared with as needed dosing, supporting the recommendation for continuous antihistamine treatment in patients with CSU123,124.

Head-to-head

While the efficacy of desloratadine has been confirmed versus placebo, a number of head-to-head trials have sought to compare the efficacy of different second-generation H1-antihistamines.

A series of studies have compared desloratadine with levocetirizine in patients with CSU. In a 4-week, multicentre, randomised, double-blind study of 886 patients with CSU, levocetirizine was shown to significantly decrease pruritic severity to a greater degree than desloratadine125. Furthermore, levocetirizine significantly increased the patients’ global satisfaction over 1 and 4 weeks compared with desloratadine, while the safety and tolerability were similar between the treatments125. Similar results were observed in a separate study where 5 mg levocetirizine was observed to be more efficacious but appeared to have a greater sedative effect than 5 mg desloratadine126. However, the difference in sedative effect was only apparent in the first two weeks of treatment and so may be clinically manageable126.

Desloratadine was also compared to rupatadine in a prospective, randomised, single centre of 56 patients with CSU who were ≥12 years of age127. After four weeks of treatment, patients receiving rupatadine saw a significant improvement in total symptom score versus desloratadine (22.5% vs. 10.8%, P<0.001). Meanwhile, the Aerius Quality of Life Questionnaire (AEQLQ), a validated QoL measure for patients with skin diseases, established that both rupatadine and desloratadine treatment resulted in a significant improvement in QoL from baseline. However, the improvement observed with rupatadine was again significantly greater than that seen with desloratadine (31% vs. 17.7%, P=0.007). No difference was observed in the incidence of adverse events between the group127.

Ebastine

While a trial published in 2017 compared the effectiveness of ebastine and levocetirizine in patients with acute urticaria128, few studies have been undertaken in patients with CSU.

The earliest clinical trial assessed the efficacy of ebastine in managing CSU compared to terfenadine, the first non-sedating antihistamine that was removed from the market due to cardiovascular concerns, and placebo129,130. In the 3-month study, ebastine provided significantly greater symptom improvements than placebo and similar improvements to terfenadine. Symptoms were considered to have improved in 73% of ebastine patients, 68% of terfenadine patients and 52% of placebo patients129.

Fexofenadine

Fexofenadine is the active metabolite of terfenadine and has been used for the management of CSU for nearly 20 years. Two double-blind, placebo-controlled trials assessed multiple doses of fexofenadine in patients with CSU and moderate-to-severe pruritus over a 4-week period131,132. Over the course of each study, all doses of fexofenadine were shown to improve CSU symptoms and lessen their impact on sleep and daily activities compared with placebo. However, doses of 60 mg twice daily and above were significantly more effective than 20 mg twice daily and had a similar adverse event profile131,132. Similar efficacy was also observed in a 6-week study of 108 Thai patients with CSU given 60 mg fexofenadine twice daily133.

Twice-daily treatment with 60 mg fexofenadine was also shown to significantly improve DLQI scores versus placebo with fexofenadine treated patients demonstrating superior work productivity, performance of daily activities and a trend towards improved classroom productivity in the small number of school-aged patients (n=26)134.

While much of the early assessment of fexofenadine was done using 60 mg twice daily, the current approved dosage in patients with CSU is typically 180 mg once daily135. The use of 180 mg once daily was evaluated in in 255 patients with CSU over a 4-week period. This multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that once-daily fexofenadine could effectively manage CSU symptoms while remaining well tolerated136. A separate study in 254 CSU patients assessed the impact of 180 mg, once-daily fexofenadine on the DLQI and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaires over 4 weeks of treatment. Patients who received fexofenadine had significantly reduced work productivity impairment, overall work impairment and activity impairment compared with patients given placebo137.

Head-to-head

There are currently a lack of high-quality head-to-head trials assessing the comparative efficacy of fexofenadine in patients with CSU.

However, an earlier comparison of fexofenadine (180 mg once daily) with cetirizine (10 mg once daily) suggested that fexofenadine was inferior to cetirizine at managing CSU symptoms. In this study of 97 patients, 51.9% of subjects treated with cetirizine were symptom free at 4 weeks compared to 4.4% of fexofenadine patients. Furthermore, while 11.5% of cetirizine patients saw no improvement, this was as high as 53.3% of patients receiving fexofenadine138. While the study was randomised and double-blinded, uncertainty over the measures used to evaluate patients and the absence of baseline symptom severity scores suggest that the data in this study should be interpreted with caution139.

Levocetirizine

Levocetirizine is the levo-enantiomer of cetirizine. Oral 5 mg once-daily dosing of levocetirizine was shown to significantly improve CSU symptoms and patient quality of life over a 6-week treatment period versus placebo140. A comparable study that evaluated treatment over 4 weeks observed that levocetirizine was superior to placebo after 1 week and this was maintained over the course of the study141.

Head-to-head

With levocetirizine being the laevorotary enantiomer of cetirizine, it would be beneficial to know if there are any significant differences between the two therapies when managing CSU. A small study treated CSU patients sequentially with levocetirizine and cetirizine for 6 weeks. While the clinical efficacy was comparable, levocetirizine was reported to have a slightly better antipruritic effect, but with a probable increase in sedation compared with cetirizine142.

Levocetirizine has been compared to a number of other second-generation antihistamines:

Levocetirizine versus bilastine

A total of 525 adult patients with CSU were included in a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of 5 mg levocetirizine, 20 mg bilastine and placebo over 4 weeks. Bilastine and levocetirizine were both significantly more effective than placebo at improving the mean total symptom score from day two onwards (Figure 24).

Figure 24. Mean improvement in total symptom score as recorded every 12 hours over 28 days in patients with a documented history of chronic urticaria (Adapted114). SE, standard error.

Bilastine and levocetirizine were also similarly effective at reducing the individual symptoms of CSU although levocetirizine produced a significantly greater change from baseline in the maximum size of hives compared with bilastine.

The most commonly reported drug-related adverse events were headache and somnolence, but the overall and drug-related incidence of adverse events was not significantly different between the treatment groups114.

Another, smaller study published in 2020 also compared the safety, efficacy and tolerability of bilastine 20 mg and levocetirizine 5 mg in adult patients with moderate-to-severe CSU over a period of 42 days. In this double-blind, randomised controlled trial, a significant improvement in UAS7, DLQI, and VAS was reported in both groups at Day 42 compared to baseline. Overall, greater improvements were observed in the bilastine group, though this difference was only significant with respect to UAS7 reduction (p=0.03). No serious adverse effects were reported in either group, though sedation was significantly less among those treated with bilastine (p=0.04)143.

Levocetirizine versus desloratadine

A multicentre, randomised, double-blind study treated 886 patients with CSU with levocetirizine or desloratadine for 4 weeks. Levocetirizine treatment resulted in a significantly greater reduction in pruritus severity, pruritus duration and mean CSU symptom scores over the course of the study compared with desloratadine. While levocetirizine appeared to be more efficacious, the safety and tolerability of the treatment was comparable125.

Levocetirizine versus loratadine

To assess whether levocetirizine and loratadine offered different treatment outcomes in patients with CSU, a randomised, open-label, outdoor-based study was performed with 60 patients. Using the total symptom score (TSS) as the efficacy measure, levocetirizine was shown to produce a significantly greater decrease in TSS than loratadine (13.32% vs. 4.85%, p<0.001) after four weeks. The incidence of adverse events was comparable between the two treatment groups144.

Levocetirizine versus rupatadine

Rupatadine is a more recently developed H1-antihistamine that is approved for the management of allergic rhinitis and urticaria. To compare its efficacy and safety to levocetirizine in patients with CSU, a randomised, single-blinded, parallel-group, outdoor-based clinical study was performed in 54 patients. While both levocetirizine and rupatadine significantly reduced the total symptoms score (TSS), the observed effect was significantly greater with rupatadine than levocetirizine (Figure 25).

Figure 25. Mean change in TSS from baseline to Week 4 (Adapted145). TSS, Total Symptom Score.

The Aerius Quality of Life Questionnaire (AEQLQ) was also used to assess any improvements in the patients’ quality of life. Using a 25% reduction in AEQLQ as a cut-off for a clinically meaningful improvement found 69% (18/26) of rupatadine-treated patients achieved a meaningful improvement in quality of life versus 21% (6/28) of levocetirizine-treated patients. Meanwhile, the incidence of adverse events was found to be comparable145.

Loratadine

Loratadine has been available for many years and is on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines146. It is a widely used and available second-generation H1-antihistamine.

Head-to-head

Comparison of loratadine to older antihistamines have shown that it has comparable efficacy but without the sedative effects that first-generation antihistamines are associated with147,148.

Loratadine has also been compared to levocetirizine in the management of CSU. In a randomised, open-label, outdoor-based study of 60 patients, levocetirizine was shown to produce a significantly greater decrease in TSS than loratadine (13.32% vs. 4.85%, p<0.001) after four weeks. The incidence of adverse events was comparable between the two treatment groups144.

Rupatadine

Rupatadine is a second-generation H1-antihistamine that offers a novel combination of potent platelet-activating factor (PAF) and histamine antagonism149,150.

Following approval in the management of allergic rhinitis, the first publication evaluating treatment potential of rupatadine in patients with urticaria was published in 2007. In a 4-week phase II, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study of 277 patients with CSU, rupatadine was observed to offer a dose-dependent reduction in urticaria symptoms.

A subsequent randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre study assessed the efficacy of 10 mg and 20 mg rupatadine over 4 weeks in 333 patients with moderate-to-severe CSU. The primary outcome was the change in mean pruritus score from baseline and this was observed to be 44.5% for placebo and 57.5% (p<0.005) and 63.3% (p<0.0001) for 10 mg and 20 mg rupatadine respectively. A fast onset of action was also observed with significant reductions in CSU symptoms observed from the first dose i.e., within 24 hours. Treatment with rupatadine also significantly improved patients’ quality of life as measured by the DLQI and the mean total symptom score (Figure 26)151.

Figure 26. Percentage reduction from baseline in mean total symptom score over 4- and 6-weeks following treatment with placebo, rupatadine 10 mg or rupatadine 20 mg (Adapted151). MTSS, mean total symptom score; Rup, rupatadine.

The most frequently reported adverse events were headache (8.0%, 4.5%, 8.3% for placebo, 10 mg and 20 mg rupatadine) and somnolence (5.3%, 2.7%, 8.3% for placebo, 10 mg and 20 mg rupatadine). The outcomes in this study indicated that 10 mg rupatadine offered similar efficacy outcomes to a 20 mg dose, but with better tolerability, in particular an incidence of somnolence comparable to placebo151. Further assessments have indicated rupatadine is a well-tolerated drug with no CNS or cardiovascular effects152.

More recently, a double-blind, randomised, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trial published in 2019 investigated the safety and efficacy of rupatadine in adult and adolescent patients with CSU153. Patients orally received either rupatadine 10 mg (n=91), rupatadine 20 mg (n=92) or placebo (n=94) once a day for 14 days153. The least squares mean total pruritus score (TPS) difference was -1.956 and -2.121 for rupatadine 10 mg versus placebo and rupatadine 20 mg versus placebo respectively (analysis of covariance, p<0.001 for both)153. Overall, the results of this study supported the use of rupatadine at 10 mg or 20 mg over placebo153. While no clinically significant adverse events were observed, it is worth noting that a dose-related increase in the incidence of adverse drug reactions was reported153.

Data also supports the efficacy of rupatadine within the real-world clinical setting. An open, prospective, non-interventional study across 146 German clinics identified 660 patients with CSU with the majority receiving 10 mg rupatadine once (n=477) or twice (n=105) daily154. At the end of their treatment, 93.2% (606/650) of patients reported an improvement in overall symptoms while a reduction in the frequency and severity of angioedema episodes was also observed. Furthermore, all domains of the CU-Q2oL quality of life questionnaire were improved while 95.7% of patients, and 87.8% of physicians, rated tolerability as very good or good154.

Efficacy of first-line rupatadine in CSU

The efficacy and safety of rupatadine has also been compared to the levo-enantiomer of cetirizine, levocetirizine. In a randomised, single-blinded, parallel-group, outdoor-based clinical study of 54 patients with CSU, both levocetirizine and rupatadine significantly reduced the TSS, although the observed effect was significantly greater with rupatadine than levocetirizine (Figure 27).

Figure 27. Mean change in TSS from baseline to Week 4 (Adapted145). TSS, Total Symptom Score.

Using a 25% reduction in the AEQLQ as a cut-off for a clinically meaningful improvement found 69% (18/26) of rupatadine-treated patients achieving a meaningful improvement in quality of life versus 21% (6/28) of levocetirizine-treated patients. Meanwhile, the incidence of adverse events was found to be comparable145.

Comparing the efficacy of second-generation H1-antihistamines

As discussed earlier in this section, high-quality clinical data on the comparative efficacy of different second-generation H1-antihistamines is scarce. This was highlighted in recent a network meta-analysis carried out by Phinyo and colleagues. This study aimed to investigate the comparative efficacy of second-generation H1-antihistamines at their licensed doses in patients with CSU112.

Three groups of treatment options were identified using a cluster ranking based on Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) values for changes in total symptom score from baseline and acceptability outcome via any cause of dropout. The first included olopatadine, fexofenadine and rupatadine, all of which were found to have high efficacy and moderate acceptability. The second group included mizolastine, bilastine, levocetirizine, loratadine and desloratadine, which had high acceptability and moderate efficacy. The third group included cetirizine, which had the lowest SUCRA ranking, as well as placebo (Figure 28)112.

Figure 28. Cluster ranking based on Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) values for changes in total symptom score from baseline and acceptability outcome via any cause of dropout (Adapted112). BILA, bilastine; CETI, cetirizine; DESL, desloratadine, FEXO, fexofenadine; LEVO, levocetirizine; LORA, loratadine; MIZO, mizolastine; OLOP, olopatadine; PLAC, placebo; RUPA, rupatadine.

The study concluded that while olopatadine, fexofenadine, bilastine, rupatadine and levocetirizine all demonstrated superior therapeutic efficacy compared to placebo, the quality of almost all studies included was low to very low, and the authors called for more rigorous head-to-head trials in the future to confirm these findings112.

The unmet medical need in CSU

H1-antihistamines are ineffective in many patients with CSU145

- Second generation H1-antihistamines fail to control symptoms in up to 50% of CSU patients at licensed doses145

- Guidelines recommend an up to four-fold dose increase of H1-antihistamine in patients with an insufficient response at licensed doses18

- It has been suggested that the increase in dose not only blocks histamine mediated effects, but also reduces mast cell activation and has an impact on various cytokine and endothelial adhesion molecules155

- Up-dosing of H1-antihistamines improves treatment responses, but up to one third of patients remain symptomatic5,18

Some second generation H1-antihistamines (e.g. cetirizine, loratadine) potentially cause sedation when licensed doses are exceeded156–160.

Second-line therapy for CSU

The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO urticaria guidelines recommend increasing the dose of second generation H1-antihistamines up to four-fold if symptoms of urticaria persist at licensed doses18

Should we up-dose second-generation H1-antihistamines?

According to the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guidelines, the recommended second-line therapy for patients who remain symptomatic despite first-line treatment is an increase in the dose of a second-generation H1-antihistamine up to four-fold the licensed dose18. A recent retrospective analysis of 178 patients lends some support to this approach with 30% of those requiring up-dosing achieving a sufficient response161. Meanwhile, a retrospective patient survey (N=319) offers further support with 40%, 42% and 54% reporting significant treatment benefits with two-, three-, and four-fold up-doing respectively. Importantly, the levels of reported adverse events and sedation were not significantly different from those observed with standard doses162. However, data on antihistamine up-dosing remains insufficient for many second-generation H1-antihistamines.

A 2015 comparative analysis included 12 published studies to evaluate the effectiveness of up-dosing different antihistamine in urticaria patients. The analysis concluded that there was no significant difference in efficacy between fexofenadine and bilastine, rupatadine and bilastine, and desloratadine and levocetirizine. However, fexofenadine, rupatadine and bilastine had significantly higher efficacy than desloratadine and levocetirizine, and rupatadine had higher efficacy than fexofenadine163.

40–50% of patients with CSU reported significant benefit from taking two- to four-fold doses of second-generation H1-antihistamines162

Within the guidelines, bilastine, cetirizine, desloratadine, levocetirizine, fexofenadine and rupatadine are cited as having studies verifying their use at increased doses18.

Clinical evidence

While the guidelines currently recommend up-dosing of second-generation H1-antihistamines for patients who remain refractory to licensed doses, some of the evidence comes from studies in patients with chronic inducible urticaria18. Here we provide an overview of the available data in patients with CSU.

Cetirizine

The evidence for up-dosing cetirizine for CSU remains quite weak164. In a small study of 22 patients with moderate-to-severe chronic urticaria who were unresponsive to licensed doses of cetirizine, up-dosing of cetirizine to 30 mg a day for one week resulted in only one patient responding satisfactorily165. However, the short timeframe of this study may limit the outcomes. CSU symptoms were significantly improved in patients (N=21) who were up-dosed and maintained on 20 mg daily compared with patients who were up-dosed for 1–2 weeks and then stepped back down to 10 mg daily166.

Desloratadine and levocetirizine

A double-blind, randomised, two parallel-armed study investigated the efficacy of weekly up-dosing of desloratadine or levocetirizine in 80 patients with CSU. Patients who became symptom-free left the study while those who continued to experience symptoms were up-dosed until reaching four-fold dosing (20 mg desloratadine or 20 mg levocetirizine). Patients who remained symptomatic after one week of four-fold treatment were switched to 20 mg of the alternative medication. Increasing the prescribed dose above 5 mg more than doubled the success rate for both treatments. However, significantly more patients were successful with levocetirizine than desloratadine and a number of patients who remained symptomatic with desloratadine achieved disease control after switching to levocetirizine (Figure 29). Patients receiving levocetirizine also reported a significantly greater improvement in discomfort from urticaria than patients given desloratadine167.

Figure 29. Percentage of patients whose symptoms were relieved by desloratadine (N=40) or levocetirizine (N=40) over the four weeks of the study. 17.5% (n/N=7/25) of patients switched from 20 mg desloratadine to 20 mg levocetirizine became symptom free. Zero patients switched from 20 mg levocetirizine to 20 mg desloratadine (n=18) became symptom free (Adapted167).

Somnolence is a significant concern when up-dosing antihistamines. Interestingly, patients reported reduced somnolence as the study went on and the antihistamine dose increased. The authors suggested that reduced urticaria symptoms and discomfort resulted in better sleep and a subsequent improvement in daytime wakefulness. Another possibility they highlight is the development of CNS tolerability to the sedative effects of both drugs.

Finally, the incidence of adverse events in this study was low and were unlikely to be associated with either treatment. No adverse events were serious enough to cause discontinuation and no changes in ECG were observed167.

A 2015 comparative study included the Staevska et al. publication within its analysis163,167. Comparison of desloratadine, levocetirizine and bilastine up-dosing revealed that significantly more patients were symptom free following treatment with bilastine (Figure 30)163.

Figure 30. Percentage of patients who were symptom free (Adapted163). QD, once daily.

Fexofenadine

While the approved dose for fexofenadine in patients with CSU is 180 mg once daily, two double-blind, placebo-controlled trials evaluated the efficacy of fexofenadine at doses of 20, 60, 120 and 240 mg twice daily131,132.

Over a 4-week trial period in 439 patients with moderate-to-severe CSU, fexofenadine produced a significant improvement in the primary efficacy outcome, mean pruritus score, compared with placebo. However, the dose response was not established beyond treatment with 60 mg twice daily (Figure 31).

Figure 31. Mean change in mean pruritus score from baseline over 4 weeks with different doses of fexofenadine (Adapted131). BID, twice daily.

While increasing the dose of fexofenadine beyond 60 mg twice daily offered small improvements in symptom relief for patients, it is worth noting that the reported adverse events were consistent across the different treatment doses and continued to be comparable to placebo131. Similar treatment outcomes and adverse event profiles were observed in another clinical trial involving 418 patients with CSU indicating that higher doses of fexofenadine offer a comparable safety profile to licensed doses but with only a modest increase in efficacy132.

The comparative analysis of trials examining up-dosing of second-generation H1-antihistamines by Sànchez-Borges et al. included the Finn et al. and Nelson et al. studies131,132,163. Comparing the percentage of patients who achieved a mean pruritus score outcome indicated that fexofenadine up-dosing to 120 mg or 240 mg twice daily was significantly less effective than rupatadine up-dosing to 20 mg once daily (p<0.0001 and p=0.03, respectively)163.

Rupatadine

While the licensed dose of rupatadine for patients with CSU is 10 mg once daily, clinical trials in this patient population have included doses up to 20 mg. In both of these studies, a trend towards improved outcomes was observed with increased treatment doses, but they did not reach statistical significance between doses151,168.

Up-dosing of rupatadine

A responder analysis pooled the results from the two trials to assess whether 20 mg of rupatadine offered clinically meaningful benefits over 10 mg rupatadine. In this study, significantly more patients achieved a ≥75% reduction from baseline in mean pruritus score, mean number of hives and mean UAS over the 4-week study periods (Figure 32169).

Figure 32. Percentage of patients achieving a ≥50% and ≥75% improvement in mean pruritus score after four weeks of treatment (Adapted169). PBO, placebo; RUP, rupatadine.

While the responder analysis suggests that 20 mg rupatadine once daily offers improved treatment outcomes compared with 10 mg once daily, the initial clinical studies suggest that the safety profile of the lower dose may be preferable151,168,169. Both clinical studies observed a modest increase in somnolence in the 20 mg treatment group151,168. However, within a real-world clinical setting this may be manageable. In a prospective, non-interventional trial involving 660 patients across 146 German dermatology clinics, 17.2% received the higher 20 mg daily dose of rupatadine. Of these patients, 76% maintained this dose and 7.3% increased it further, suggesting that higher doses of rupatadine are tolerable for the majority of patients154.

The 2015 comparative analysis by Sànchez-Borges et al. also included the rupatadine studies151,163,168. In the analysis, up-dosing of rupatadine was found to significantly improve the mean pruritus score versus fexofenadine 120 mg and 240 mg (Figure 33)163.

Figure 33. Comparison of fexofenadine and rupatadine up-dosing as assessed by patients achieving outcomes in mean pruritus score (Adapted163).

Third- and fourth-line therapy for CSU

The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO urticaria guidelines recommend omalizumab as add-on therapy to second-line treatment if symptoms of urticaria persist. For exacerbations a short course (maximum 10 days) of glucocorticosteroids can be considered18.

Omalizumab is an anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) humanised monoclonal antibody160. Omalizumab 300 mg is approved in the European Union and the United States of America for the treatment of CSU (also known as chronic idiopathic urticaria [CIU]) in adult and adolescent (12 years and above) patients with inadequate response to H1-antihistamine treatment or who remain symptomatic despite H1-antihistamine treatment170,171.

Clinical evidence

Aside from the standard treatment using second-generation H1-antihistamines, a number of alternatives are available for cases where the patient is refractory or intolerant to these medications. Here we present the evidence from clinical studies on the available treatment options, including omalizumab, ciclosporin, montelukast, oral corticosteroids and other less proven medications.

Omalizumab

Results from the three pivotal Phase III trials, ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL supported the efficacy, safety and tolerability of omalizumab in refractory CSU172–174.

Efficacy

Omalizumab significantly improved itch versus placebo in Phase III studies of refractory CSU patients (Figure 34)172–174.

Figure 34. Improvement in itch severity score (ISS) was significantly greater with all doses of omalizumab vs. placebo at Week 12 (mITT) (Adapted172–174). ISS, Itch Severity Score ; mITT, modified intention-to-treat.

In these Phase III studies, omalizumab 300 mg consistently provided significant improvements in the symptoms of CSU compared with placebo172–174.

- A significant proportion of patients became either completely free of itch and hives (range 34–44%; p<0.001 to p<0.0001) or had their symptoms suppressed to levels described as ‘well controlled disease’ at 12 weeks (52–66%, p<0.0001)172–175.

- Weekly itch severity score (ISS) was significantly reduced by 62–71% from baseline to Week 1, with itch relief being rapid and sustained throughout the treatment period172–174,176.

- The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was significantly reduced (i.e. QoL improved) at 12 weeks in ASTERIA I (-10.3 vs. -6.1, p=0.0001), ASTERIA II (-10.2 vs. -6.1, p=0.0004) and GLACIAL (-9.7 vs. -5.1, p<0.001), corresponding to a 74%, 78% and 73% reduction vs. baseline172–175.

- The weekly hives score was significantly reduced (i.e. fewer hives) at 12 weeks in ASTERIA I (-11.4 vs. -4.4, p<0.0001), ASTERIA II (-12.0 vs. -5.2, p<0.001) and GLACIAL (-10.5 vs. -4.5, p<0.001), corresponding to a 67%, 74% and 62% reduction vs. baseline172–175.

- Proportion of angioedema-free days over weeks 4–12 were significantly increased in GLACIAL (91% vs. 88.1%, p<0.001)174.

Results from the open-label Phase IV SUNRISE study of omalizumab in adults with CSU (n=136) nonresponsive to H1-antihistamine therapy suggest that approximately 75% of patients achieve disease control after 12 weeks of treatment177.

The Phase IV Xolair Treatment Efficacy of Longer Duration in Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria (XTEND-CIU) study was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial including CSU patients (n=205) between the ages of 12 and 75 years. After a 24-week open-label period of omalizumab 300 mg every four weeks, patients were stratified by 7-day Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7): a UAS7 of ≤6 (protocol-defined responder) vs UAS7 >6 (non-responders). Responders subsequently entered a 48-week double-blind phase and were assessed for clinical worsening vs placebo (Figure 35)178.

Figure 35. XTEND-CIU study design (Adapted178). CIU, chronic idiopathic urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; UAS7, 7-day Urticaria Activity Score; Q4W, every four weeks; XTEND, Xolair Treatment Efficacy of Longer Duration in Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria.

During the open-label phase, patients with moderate-to-severe CIU symptoms at baseline demonstrated improvements in the UAS7 as early as Week 1, which continued to Week 24. In total, 73.0% and 52.0% of patients were considered as responders (UAS7 ≤6) or complete responders (UAS7 = 0) at Week 24, respectively.178.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria was formerly known as chronic idiopathic urticaria and the two terms are used interchangeably in this section42