Topical scientific insights

Understanding Pouchitis

Pouchitis may develop in about 70% of the patients who undergo IPAA1, the preferred surgical treatment for refractory or complicated ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP):

- Discover the prevalence and burden of pouchitis

- Learn about the risk factors associated with pouchitis

- Understand the roadblocks to controlling pouchitis in patients

What is pouchitis?

Pouchitis refers to inflammation of the ileal pouch1,2. It is associated with a range of non-specific digestive symptoms and can lead to impaired quality of life and disability3.

Acute pouchitis is the most common non-surgical complication of restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA), the preferred surgical treatment for refractory or complicated ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)4,5. This procedure involves resection of the colon and rectum with preservation of the anal sphincters, followed by IPAA, by which faecal continence is maintained6.

Pouchitis can be classified based on disease duration (acute or chronic), treatment response (responsive, dependent, or refractory), and secondary causes (secondary infection, surgery related mechanical complications and, NSAID use)5.

Although a total proctocolectomy with IPAA can be curative for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) related neoplasia pouchitis develops in up to 80% of patients who undergo this procedure (40% within one year of surgery)4. Though a number of hypotheses have been proposed regarding the potential causes of pouchitis, the precise pathogenesis of this condition remains elusive2.

What are the risk factors for pouchitis?

Total proctocolectomy with IPAA can be used to treat both UC related neoplasm and FAP; however, pouchitis develops in 0-11% of patients with FAP who undergo this procedure2. This suggests that the underlying pathogenesis of UC related inflammation may play a role in the development of this condition2.

Other risk factors for pouchitis include7:

- genetic mutations

- extensive colitis

- rheumatologic disorders

- primary sclerosing cholangitis

A better understanding of these risk factors could help inform prophylaxis and manage patient expectations8,9.

What are the symptoms of pouchitis?

Symptoms of pouchitis are similar to those of ulcerative colitis, including more frequent bowel movements, faecal urgency, straining during defecation, incontinence, abdominal/pelvic pain, haematochezia, fever and malaise2,7. In some cases, extraintestinal manifestations affecting the joints, eyes, skin and liver may also be present10.

The symptoms of pouchitis are non-specific and do not always reflect endoscopically and/or histologically determined disease severity10

These symptoms could be caused by various other conditions including cuffitis, Crohn’s disease of the pouch and irritable pouch syndrome11. It is therefore difficult to conclusively diagnose pouchitis based on symptoms alone, and a pouchoscopy may be required to rule out differential diagnoses12.

What unmet needs remain in pouchitis?

Screening protocols

Screening for metabolic complications and identifying those at high risk of developing pouchitis and pouch failure are important aspects of the management of patients who have undergone a restorative proctocolectomy with IPAA9.

Pouchoscopy is currently only recommended in postoperative patients who are exhibiting symptoms of pouchitis1. However, around half of asymptomatic patients have abnormal endoscopic findings following their surgery1. An association between mucosal erosion or ulceration and subsequent development of primary acute idiopathic pouchitis has been identified in nearly a quarter of asymptomatic pouch patients 1,13. In a study of 143 asymptomatic pouch patients, primary acute idiopathic pouchitis occurred in 44 (31%) patients and chronic idiopathic pouchitis in 12 (8.4%) patients over a median follow-up period of 3.03 [IQR 1.24–4.60] years13. Nevertheless, standardised strategies of proactive monitoring for postoperative patients who do not exhibit symptoms of pouchitis have not been established1.

Disease evaluation tools

Overall, there is a lack of validated tools for evaluation of pouchitis disease activity14. The Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI) is currently the most popular disease activity assessment tool used in clinical trials, but is rarely used in day-to-day clinical practice15. The PDAI was originally developed as a diagnostic tool, so its suitability as an evaluative tool in the clinical trial setting is not known14. The PDAI has three components16:

- Clinical symptoms

- Endoscopic findings

- Histological findings

A diagnosis of pouchitis from only subjective measures of disease activity, such as self-reported symptoms, can lead to under- or overassessment. Including endoscopic and histological data is therefore necessary for more accurate patient evaluation.

The modified PDAI (mPDAI) uses a simplified list of diagnostic criteria and does not require histological analysis of patients, but its sensitivity and specificity are comparable to that of the PDAI17. Further efforts to develop validated tools for disease activity assessment and standardisation of clinical trial endpoints and definitions will be crucial to the successful development of new drugs to treat pouchitis14.

Treatment

The primary treatment for acute pouchitis is antibiotic therapy (e.g. ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, or rifaximin)1,12. Patients with chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis may also benefit from treatment with aminosalicylates, steroids, immunomodulators and biologics (Figure 1)1,8,18.

Figure 1. General treatment protocol for pouchitis (Adapted1). 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; PO, per os; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Treating chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis can be challenging8. Randomised controlled trials investigating the treatment of chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis are scarce; therefore, the treatment of this condition remains somewhat empirical8. However, in early 2022, based on the results of the EARNEST trial, vedolizumab became the first therapy to receive approval from the European Commission for the treatment of patients with moderately-to-severely active chronic pouchitis who have undergone proctocolectomy and IPAA for ulcerative colitis and had an inadequate response or lost response to antibiotic therapy19.

On the horizon

Though antibiotics are still considered the mainstay of treatment for acute pouchitis, research into newer treatment options for chronic pouchitis has yielded promising results. Various potential treatments, including biological therapies, are currently being studied in these patients1,20.

In addition to treatments under development for pouchitis, research into deep learning models using artificial intelligence (AI) for the prediction of pouchitis, has recently been published. For example, one study, which used a convolutional neural network as a deep learning model, found that the prediction rate of this model was 84%16. This was more than 20% higher than that achieved using mPDAI before ileostomy closure16. In the future, such models could be used to help facilitate earlier intervention in patients at risk of developing pouchitis16.

Learn more about surgery in IBD here

References

- Akiyama S, Rai V, Rubin DT. Pouchitis in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Intest Res. 2021;19(1):1-11.

- Schieffer KM, Williams ED, Yochum GS, Koltun WA. Review article: the pathogenesis of pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(8):817-835.

- Trang-Poisson C, Kerdreux E, Poinas A, Planche L, Sokol H, Bemer P, et al. Impact of fecal microbiota transplantation on chronic recurrent pouchitis in ulcerative colitis with ileo-anal anastomosis: study protocol for a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):455.

- Barnes EL, Herfarth HH, Kappelman MD, Zhang X, Lightner A, Long MD, et al. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Pouchitis and Pouch-Related Complications in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(8):1583-1591.e4.

- Dalal RL, Shen B, Schwartz DA. Management of Pouchitis and Other Common Complications of the Pouch. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(5):989-996.

- Luo WY, Singh S, Cuomo R, Eisenstein S. Modified two-stage restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational research. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35(10):1817-1830.

- Rabbenou W, Chang S. Medical treatment of pouchitis: a guide for the clinician. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211023376.

- Outtier A, Ferrante M. Chronic Antibiotic-Refractory Pouchitis: Management Challenges. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2021;14:277-290.

- Ardalan ZS, Sparrow MP. A Personalized Approach to Managing Patients With an Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;6:337.

- Zezos P, Saibil F. Inflammatory pouch disease: The spectrum of pouchitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(29):8739-8752.

- Gionchetti P, Calabrese C, Laureti S, Poggioli G, Rizzello F. Pouchitis: Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:3871-3879.

- Hata K, Ishihara S, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Kiyomatsu T, Tanaka T, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis: Diagnosis, management, risk factors, and incidence. Dig Endosc. 2017;29(1):26-34.

- Kayal M, Plietz M, Radcliffe M, Rizvi A, Yzet C, Tixier E, et al. Endoscopic activity in asymptomatic patients with an ileal pouch is associated with an increased risk of pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(11-12):1189-1194.

- Sedano R, Ma C, Pai RK, Haens GD, Guizzetti L, Shackelton LM, et al. An expert consensus to standardise clinical, endoscopic and histologic items and inclusion and outcome criteria for evaluation of pouchitis disease activity in clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53(10):1108-1117.

- Shen B, Lashner BA. Diagnosis and treatment of pouchitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2008;4(5):355-361.

- Mizuno S, Okabayashi K, Ikebata A, Matsui S, Seishima R, Shigeta K, et al. Prediction of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis using artificial intelligence and deep learning. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26(6):471-478.

- Verstockt B, Claeys C, De Hertogh G, Van Assche G, Wolthuis A, D'Hoore A, et al. Outcome of biological therapies in chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis: A retrospective single-centre experience. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(9):1215-1225.

- Barreiro-de Acosta M, Baston-Rey I, Calvino-Suarez C, Enrique Dominguez-Munoz J. Pouchitis: Treatment dilemmas at different stages of the disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(3):256-262.

- Matsumoto R. European Commission Approves Vedolizumab IV for the Treatment of Active Chronic Pouchitis. www.takeda.com. Published February 3, 2022. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://www.takeda.com/newsroom/statements/2022/european-commission-approves-vedolizumab-iv-for-the-treatment-of-active-chronic-pouchitis/

- LeBlanc J-F, Segal JP, de Campos Braz LM, Hart AL. The Microbiome as a Therapy in Pouchitis and Ulcerative Colitis. Nutrients 2021;13(6):1780.

Novel Diagnostic Techniques

With advancements in diagnostic techniques across the medical field, coupled with the exponential rise in technological innovations, it is not surprising to find that these two areas can perfectly co-exist. Read on to discover how the marriage of tech and the need to better diagnose illnesses can result in a pill sized camera which can be swallowed by patients to provide live internal images.

Can swallowing a tiny camera really help check signs of Crohn’s disease and other gastrointestinal conditions?

Thousands of patients to swallow pill-sized cameras but can this new technology:

- provide an alternative means to colon capsule endoscopy used in other diseases?

- aid with the low numbers of endoscopies being carried out due to the pandemic?

To date, limited trials have investigated the potential of swallowing a small capsule to replace colonoscopy in detecting cancer1. However, a trial of this new technology is currently being carried out by the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom. An initial group of 11,000 NHS patients will be trialed at 40 different sites across England whereby patients will swallow pill-sized cameras to check for bowel cancer2.

These mini cameras pass through the body and take photos, checking for signs of cancer and other conditions such as Crohn’s disease2,3. Crohn’s disease is one form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that affects over 0.3% of the population in many regions of Europe, North America and Oceania4. The pathogenesis of Crohn’s is not well understood but is thought to involve the innate and immune responses. Although there is no current cure for the disease, management of Crohn’s disease includes exploiting several inflammatory targets5.

Current ways of detecting Crohn’s disease

Traditionally, Crohn’s disease is diagnosed using a combination of tests, including a physical exam, diagnostic tests, laboratory tests and intestinal endoscopy, the latter being the most accurate method of all. More specifically, it involves colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy and enteroscopy, all of which provide access to the colon and small intestine6.

Colonoscopy and endoscopy are key tools for physically examining and diagnosing Crohn’s disease, photos of which can be seen in our current IBD learning zone. Depending on the severity of Crohn’s (mild, moderate, or severe type), characteristic skip lesions and a cobblestone appearance can be observed7. More so, as the disease becomes more serious, systemic complications may also begin to develop8,9.

Although colonoscopy and endoscopy have proven very useful in detecting cancer, Crohn’s disease, and other gastrointestinal disorders, they also come with potentially serious complications and the risk of adverse events (such as bleeding) has been studied extensively9. It is therefore thought that a small pill-sized camera that can be swallowed would be a significant innovation in the field of IBD detection and Crohn’s disease and would also prove very useful in avoiding such complications.

Replacing old detection methods with new, innovative ones

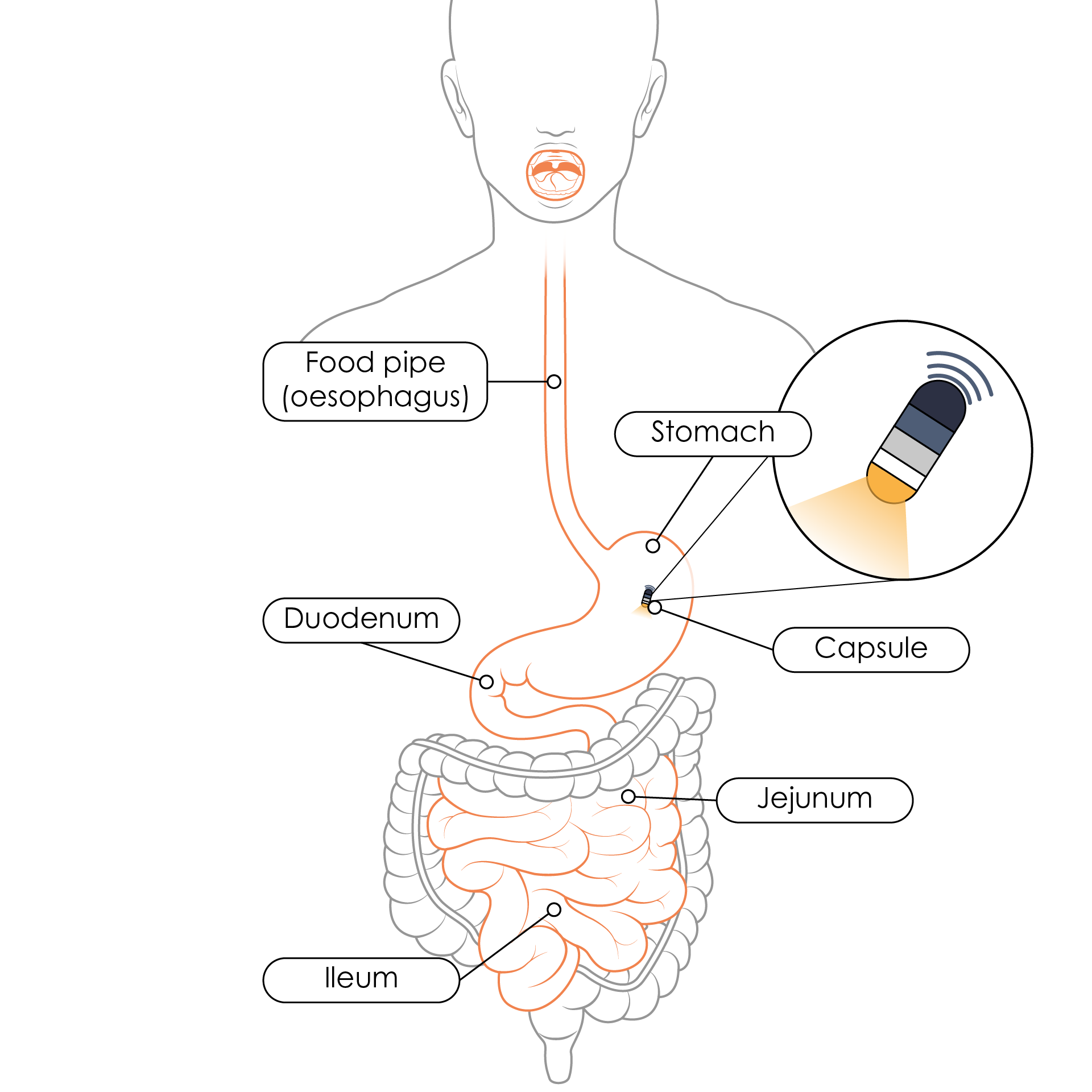

Tiny cameras that can be swallowed and record images would also be a novel and safer alternative to endoscopy and colonoscopy. These travel through the oesophagus to the stomach and small bowel after being swallowed (Figure 1), and the ones that have already been tested or are being tested use a system that includes innovative features. Such features support image acquisition uniquely suited to a patient’s motility as well as tools used to record and interpret the results10. The software uses advanced algorithms which provide the tools needed to read and understand the study results10. It is believed to have great potential to diagnose Crohn’s disease and other gastrointestinal conditions. This is expected to replace traditional endoscopy and provide a diagnosis within hours.

Figure 1. Route of a capsule once swallowed and the organs that can be visualised using the capsule camera (Adapted11).

The current NHS trial is being performed on an initial group of 11,000 patients in England who are due to receive the capsules in more than 40 parts across the country2. The NHS has currently given priority to use it in cancer care, but it is believed that these tiny cameras hold great potential to be used for other conditions too, specifically gastrointestinal diseases such as Crohn’s disease2.

A solution for the lack of colonoscopy attendance amidst the pandemic

Another reason that the NHS has pushed ahead with this innovation is because it has proven particularly useful in the current era of the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent study by the University of Oxford showed that fewer traditional endoscopies are currently performed due to fear of going to the hospital and getting infected with COVID-1912,13. A second study by Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust reported a freeze on endoscopy activity during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic14.

Concerns about endoscopy lists running at reduced capacity (for safety reasons) as well as worry about a potential surge in demand post-COVID have led to NHS England and the Scottish government funding capsule endoscopy as a primary diagnostic tool13,14. More so, studies have shown that as a tool it is 87% sensitive compared to colonoscopy when used to detect polyps and that it can find lesions missed by colonoscopy14. Also, meta-analyses showed an 80% sensitivity by capsule endoscopy when used to detect Barrett’s oesophagus14.

For the reasons described above it is believed that capsules like the one being trialed by the NHS can offer a solution to previous problems that arise by endoscopy by allowing patients to conveniently conduct the procedure at home. It is considered a non-invasive and quick technique and provides patients with the possibility of getting tested without having to visit a hospital and putting themselves at risk of COVID-1914.

Learn more about Crohn’s disease

References

- Loyola University Health System. New alternative to colonoscopy is as easy as swallowing a pill -- ScienceDaily. 2017. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/03/170315144501.htm. Accessed 22 June 2021.

- ITV. Thousands of patients to swallow cameras the size of a pill to check for cancer; ITV News. 2021. https://www.itv.com/news/2021-03-11/thousands-of-nhs-patients-to-swallow-tiny-cameras-to-check-for-bowel-cancer. Accessed 22 June 2021.

- Robertson K. and Singh R. Capsule Endoscopy - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482306/. Accessed 23 June 2021.

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769–2778.

- Aggeletopoulou I, Assimakopoulos SF, Konstantakis C, Triantos CC. Interleukin 12/interleukin 23 pathway: Biological basis and therapeutic effect in patients with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(36):4093–4103.

- NIH. Diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease | NIDDK. 2017. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/crohns-disease/diagnosis. Accessed 22 June 2021.

- Jung SA. Differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: What is the role of colonoscopy? Clinical Endoscopy. 2012;45(3):254–262.

- Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Parc R, et al. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8(4):244–250.

- Thia KT, Sandborn WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Loftus E V. Risk factors associated with progression to intestinal complications of Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1147–1155.

- Medtronic. PillCamTM SB 3 Capsule | Medtronic (UK). 2013. https://www.medtronic.com/covidien/en-gb/products/capsule-endoscopy/pillcam-capsules/pillcam-sb-3-capsule.html. Accessed 22 June 2021.

- Young Crohns. IBD Basics: Endoscopy •. 2018. https://youngcrohns.co.uk/blog/crohns/ibd-basics-endoscopy/. Accessed 22 June 2021.

- NHS England » NHS rolls out capsule cameras to test for cancer. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2021/03/nhs-rolls-out-capsule-cameras-to-test-for-cancer/. Accessed 22 June 2021.

- Morris EJA, Goldacre R, Spata E, Mafham M, Finan PJ, Shelton J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the detection and management of colorectal cancer in England: a population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(3):199–208.

- McAlindon M. COVID-19: Impetus to the adoption of capsule endoscopy as a primary diagnostic tool? Frontline Gastroenterology. 2021;12(4):263–264.

of interest

are looking at

saved

next event

Developed by EPG Health for Medthority in collaboration with Takeda, with some content provided by Takeda.. Please refer to your local prescribing information before using any treatment described on the website as they may not have received the relevant approvals or could be unavailable in your area.

C-ANPROM/INT/IBDD/0041 October 2021.

C-ANPROM/INT/IBDD/0059 July 2022.