Understanding ulcerative colitis

Improve your ability to support patients with ulcerative colitis.

- Visualise the pathogenesis with our diagrammatic overview

- Discover how disease severity is determined with endoscopic imagery

- Get to grips with the ongoing evolution of therapeutic targets

In this section

Epidemiology

Prevalence and incidence

Ulcerative colitis has a higher prevalence than Crohn’s disease in adults1,2. It is a chronic, progressive, relapsing and remitting condition characterised by continuous inflammation of the colonic mucosa3–5. As in Crohn’s disease, there are regional variations in the prevalence and incidence of ulcerative colitis, but an overall global increase has been consistently reported6–9.

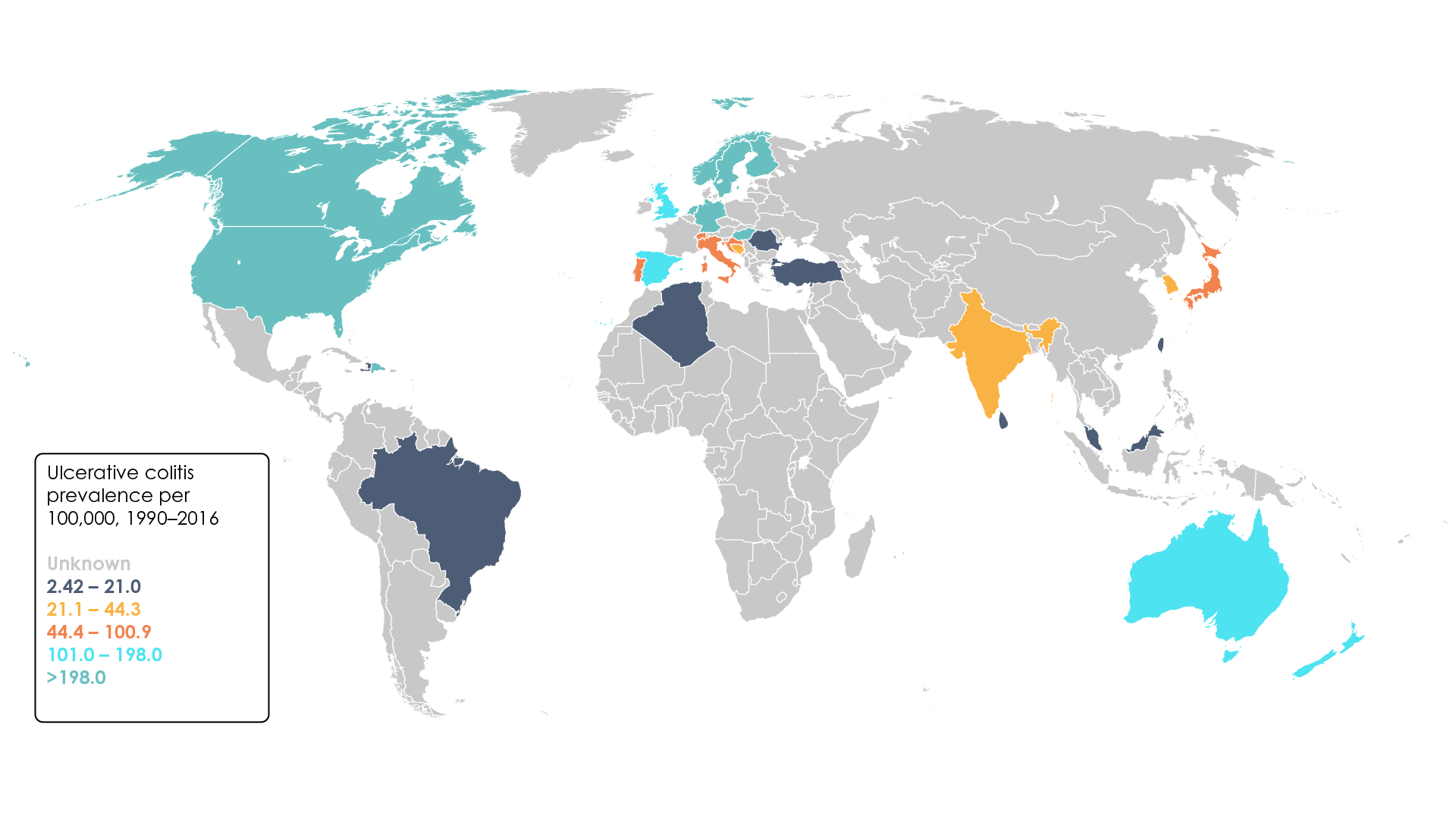

A systematic review investigating the worldwide prevalence and incidence of ulcerative colitis revealed that the prevalence was highest in Europe (505 cases per 100,000 individuals) and North America (249 cases per 100,000 individuals) (Figure 1)10. Within these regions, the highest prevalence values have been reported in Norway and the United States11.

Figure 1. Worldwide ulcerative colitis prevalence per 100,000, 1990–2016 (Adapted11).

Overall, incidence of ulcerative colitis is increasing globally, though there is substantial variation between different populations and geographical regions, with estimates ranging from 0.5–31.5 cases per 100,000 individuals each year9,12,13. In recent years, newly industrialised countries have experienced a particular surge in the number of new cases reported annually. In Brazil, for example, the annual percentage change has recently been calculated at 14.9% (95% confidence interval 10.4–19.6)11.

Disease development

In contrast to Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis is generally thought to be equally as common in males as in females across all age groups5. It can develop at any age from infancy onwards, but most frequently presents in adolescents and other patients under 30 years of age3. Interestingly, there is a second, albeit less pronounced peak between the ages of 50 and 80 years old, with incidence of ulcerative colitis on the rise in patients over the age of 65 years3,14.

Aetiology

Though the exact causes of ulcerative colitis are not well understood, experts have identified several important factors that are thought to contribute to the development of this disease5,15.

Genetic susceptibility

A family history of IBD is considered the most important risk factor for developing ulcerative colitis and has been reported in 8–14% of patients16,17. Indeed, first-degree relatives of patients with IBD are four times more likely to develop ulcerative colitis17. Rates of ulcerative colitis also vary between different ethnic groups and, like Crohn’s disease, it is particularly prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews, providing further evidence of a genetic component18.

In a 2017 review, it was reported that genome-wide associated studies (GWAS) have now identified over 200 susceptibility loci for IBD. Of these, 137 confer a higher risk of developing both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, while a further 27 are specific to ulcerative colitis19. These susceptibility loci include human leukocyte antigen and genes associated with barrier function17. However, these “identified genetic factors” can only account for around 8% of the disease variance and therefore have poor predictive capacity and are of little use in a clinical setting17,19.

Gut flora

Reduced microbial diversity of the gut has been reported in patients with both ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease20. In genetically predisposed individuals, the resultant state of dysbiosis may lead to onset of disease21,22. Loss of commensal bacteria, particularly those belonging to the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla, is accompanied by the loss of their protective benefits22. It remains to be seen whether the dysbiosis observed in patients with ulcerative colitis is the cause of their condition, or simply a consequence of chronic mucosal inflammation. However, it is worth noting that the extent of dysbiosis in these patients is less severe than in patients with Crohn’s disease17.

Interestingly, loss of Faecalibacterium has been consistently reported in patients with IBD. Early studies in mouse models suggest that this bacteria could be used in the treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis in the future22.

Environmental factors

Childhood exposure to enteric pathogens, such as with Campylobacter and Salmonella, has been shown to increase the risk of developing IBD23.However, paradoxically the introduction of more stringent hygiene practices and increased antibiotic use in industrialised countries and resultant reduction in microbial exposure during childhood, may hamper the development of the innate immune system24. As a result, the immune system may not be able to coordinate an appropriate response when challenged with unfamiliar microorganisms in adulthood, increasing ulcerative colitis risk24.

Unlike in Crohn’s disease, active smoking has been shown to confer protection against ulcerative colitis5. Furthermore, it has been reported that smoking cessation increases risk of developing ulcerative colitis and that this state of elevated risk persisted for as long as 20 years3. However, it is worth noting that this observation has been called into question by Indian studies which found no association between current- or ex-smoker status and ulcerative colitis5,25,26.

Appendectomy is also thought to reduce ulcerative colitis risk, though its relationship with Crohn’s disease is less clear5,27. Paradoxically, undergoing an appendectomy after receiving an ulcerative colitis diagnosis is thought to detrimentally affect the course of the disease5.

Host immunity

The mechanism by which the immune response results in development of ulcerative colitis is considered in the pathophysiology section in this part of the Learning Zone.

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis is not well understood; however, it is thought to be similar to that of Crohn’s disease, though some important differences have been identified17.

In ulcerative colitis, thinning of the mucus layer contributes to impairment of the epithelial mucosal barrier21.

A range of different factors contribute to ulcerative colitis pathogenesis5.

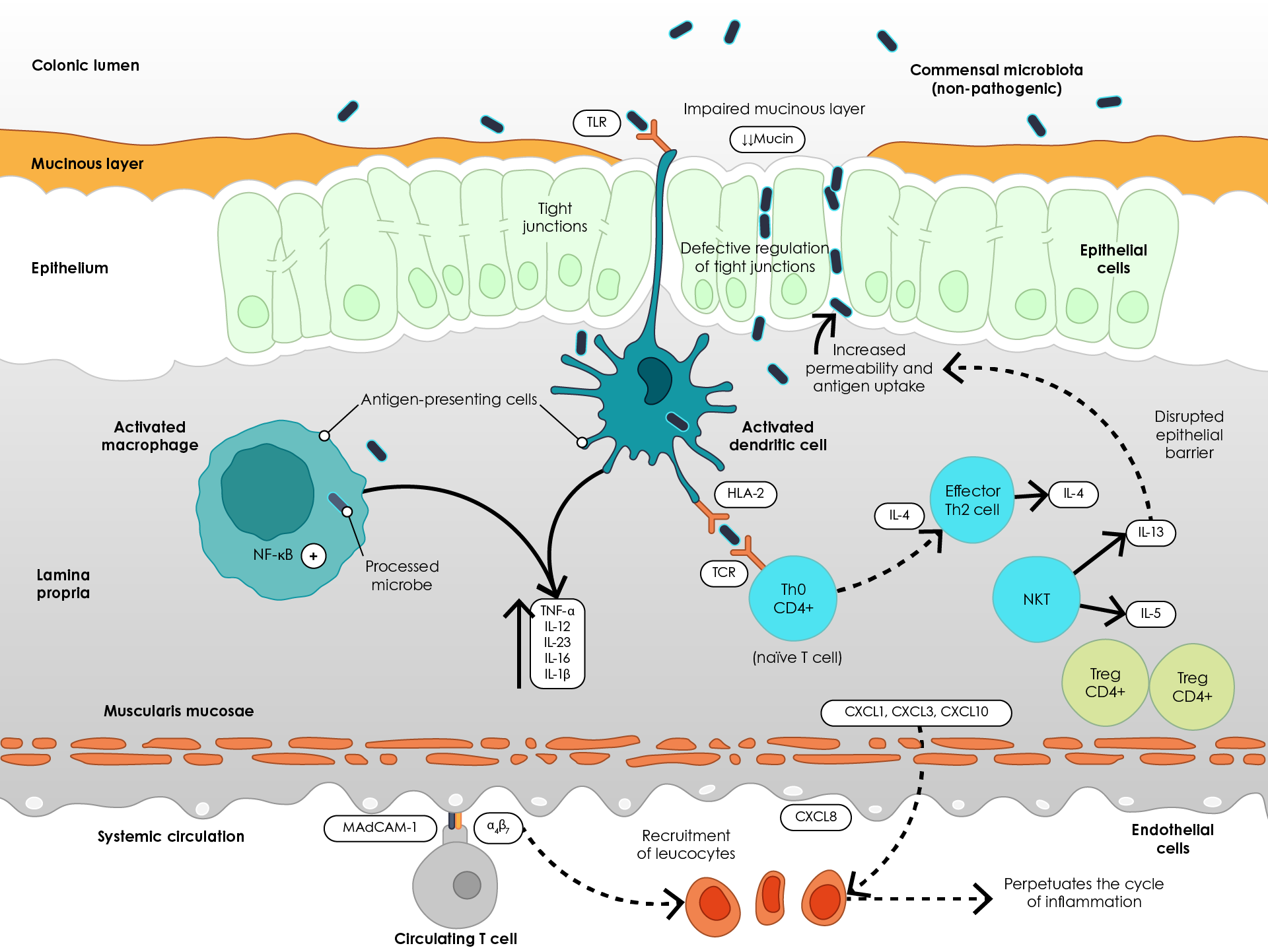

Following increased intestinal epithelial permeability, innate immune cells, such as macrophages, recognise bacterial antigens via toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) and become activated28. This leads to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines – tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-2328,29. Processed antigens are presented to T helper (Th) cells via T cell receptors (TCRs), facilitating an adaptive immune response and production of IL-4, while natural killer T (NKT) cells produce IL-13 and IL-5, further disrupting the epithelial barrier29. Furthermore, leucocyte recruitment increases through mechanisms such as upregulation of pro-inflammatory chemokines (CXCL) and binding of integrin (α4β7)-bearing T cells to colonic endothelial cells via mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 (MAdCAM-1) (Figure 2)30.

Figure 2. Pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis (Adapted29). α4β7, Integrin α4β7; CXCL, Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; HLA-2, Human leukocyte antigen 2; IL, Interleukin; MAdCAM-1, mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1; NF-κB, Nuclear factor- κB; NKT, Natural killer cell; TCR, T cell receptor; Th2, T helper 2 cell; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNFα, Tumour necrosis factor α; Treg, Regulatory T cell.

Clinical presentation

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic disease that involves relapsing and remitting inflammation of the colon17. Unlike in Crohn’s disease, this inflammation is confined to the mucosa and sub-mucosa and tends to be continuous rather than patchy31.

The symptoms of ulcerative colitis vary depending on the extent of colonic involvement, with bloody diarrhoea the most common symptom17. Other common symptoms include urgency, incontinence, fatigue, increased frequency of bowel movements, mucus discharge, nocturnal defecations and abdominal discomfort32.

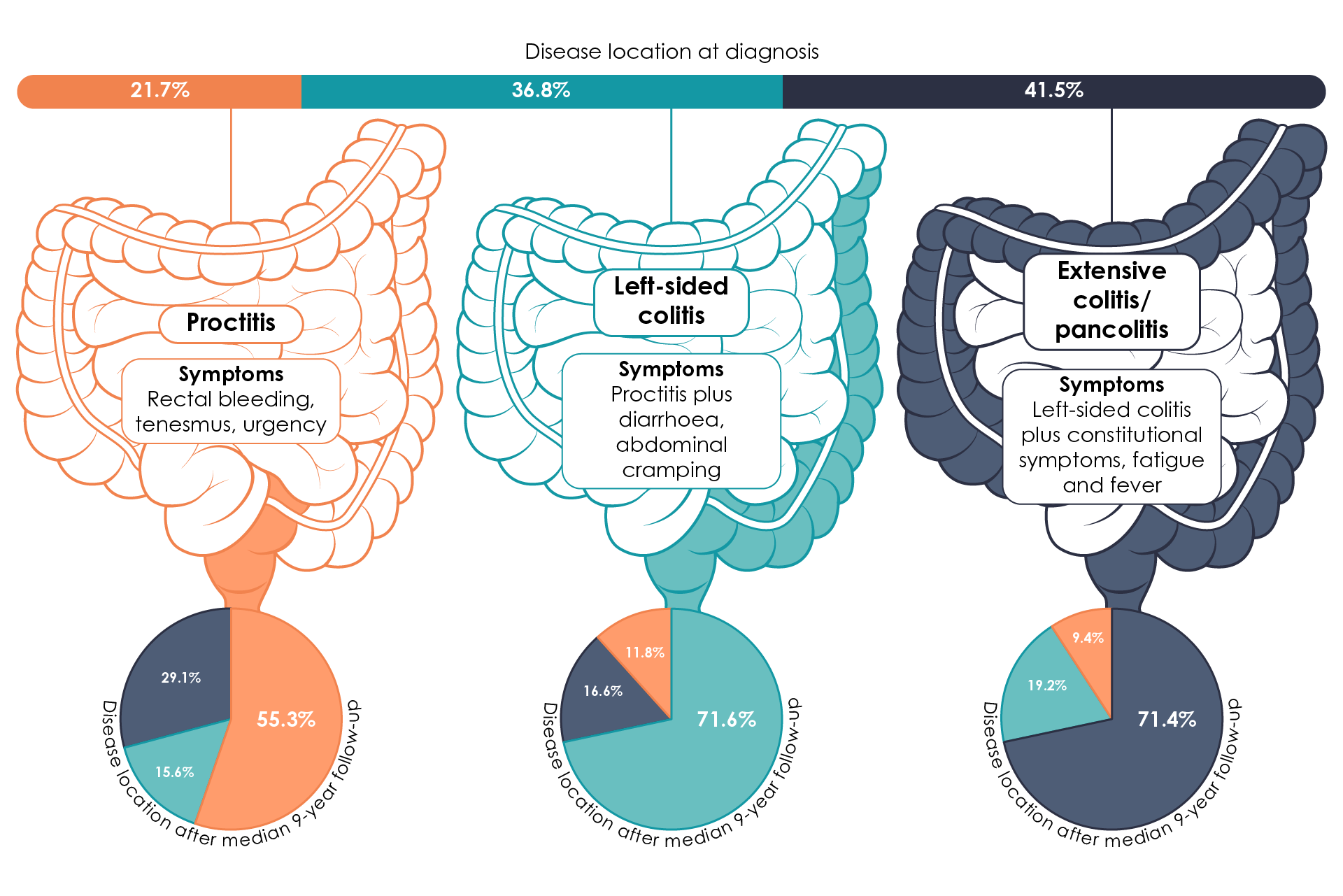

It has been estimated that around 16% of ulcerative colitis patients experience disease progression over the course of 9 years (Figure 3)33.

Figure 3. Montreal Classification of ulcerative colitis, showing disease phenotype and disease progression over 9 years (Adapted17,33,34).

Treatment goals

Evolution of treatment goals and treat-to-target

In the past, the goal of treatment in IBD was to achieve symptomatic relief, preferably without the need for glucocorticoids35. More recently, it has been established that absence of symptoms does not necessarily indicate absence of inflammation, leading to the introduction of more stringent treatment targets35,36.

The concept of a treat-to-target approach in ulcerative colitis is still relatively new, having first been defined in 201537. The treat-to-target strategy involves adjusting therapy based on whether or not patients meet predefined treatment response targets, encouraging personalisation of care and earlier intervention36,38.

Despite being met with enthusiasm by experts around the world, many physicians have been slow to adopt this new disease management style and still consider symptomatic control an adequate treatment target36.

Consensus definition of targets in ulcerative colitis: STRIDE

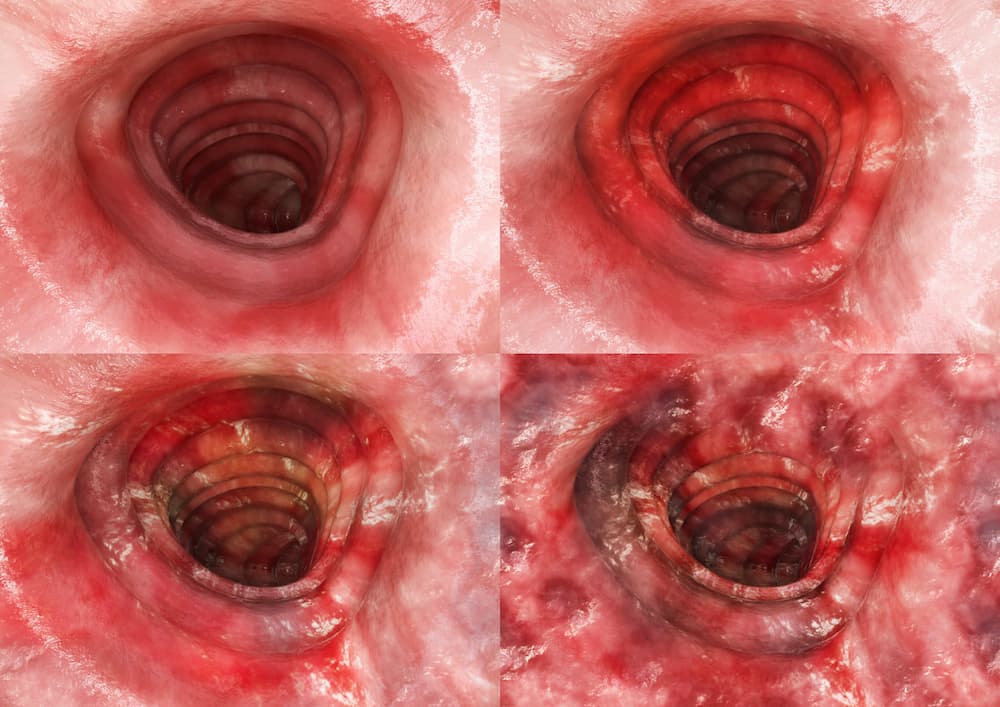

The Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) programme assessed potential treatment targets for patients with IBD to facilitate a treat-to-target strategy. As in Crohn’s disease, the expert-consensus definition of treatment targets in ulcerative colitis combines clinical (patient-reported) remission and endoscopic (clinician-reported) remission. In ulcerative colitis, clinical/patient-reported outcome (PRO) remission is defined as resolution of rectal bleeding and diarrhoea or altered bowel habit, while endoscopic remission is defined as a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0–1 (Figure 4)37,39.

Figure 4 . Understanding Mayo endoscopic sub-scores (a) Score 0, normal mucosa; (b) Score 1, mild disease with erythema, decreased vascular pattern and mild friability; (c) Score 2, moderate disease with marked erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability and erosions; (d) Score 3, severe disease with spontaneous bleeding and ulceration40.

The STRIDE statements were recently updated to reflect new evidence regarding treatment optimisation in IBD39. STRIDE-II provides confirmation of the long-term treatment targets identified in STRIDE-I, with the addition of absence of disability, restoration of quality of life and normal growth in paediatric patients39. STRIDE-II also lists symptomatic relief and normalisation of serum and faecal markers as suitable short-term targets39.

Role of mucosal healing

Mucosal healing is now considered an important treatment target in ulcerative colitis, consistently predicting favourable patient outcomes across a number of studies41. In the past, mucosal healing was assessed endoscopically. Today, a revised definition of mucosal healing incorporates both endoscopic and histologic healing42,43.

Mucosal healing is defined as endoscopic healing plus histologic healing42,43.

A recent European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) position paper highlighted the lack of standardised histological procedures, definitions and scoring systems in ulcerative colitis44. Though the authors recognised that further research will be required to fully understand the relevance of histologic disease activity in this field, they proposed absence of intra-epithelial neutrophils, erosion and ulceration as the minimum requirement for histological remission44. Given the association between persistent histological inflammation and adverse outcomes in ulcerative colitis, histological remission is now considered a treatment target for patients with this disease44.

Role of early intervention

The benefits of early intervention with biological therapy are less well-established in ulcerative colitis as compared to Crohn’s disease43,45–47. This is reflected in the continued use of a “step-up” approach when treating ulcerative colitis, whereby treatment is escalated based on the severity of clinical symptoms43.

Current evidence does not support early intervention with biological therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis, but research is ongoing43.

Research into the efficacy of top-down versus step-up approaches in ulcerative colitis is ongoing, with the SPRINT study among those set to shed light on the long-term implications of early intervention. However, as yet early intervention with a biologic therapy is not supported by available evidence43.

References

- Tanaka A. IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut Liver. 2019;13(3):300–307.

- Ulcerative Colitis - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459282/. Accessed 10 February 2021.

- Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Jimenez G, Catinella AP, Ng N, Umapathy C, et al. A comprehensive review and update on ulcerative colitis. Dis Mon. 2019;65(12):100851.

- Dart RJ, Samaan MA, Powell N, Irving PM. Vedolizumab: Toward a personalized therapy paradigm for people with ulcerative colitis. Clinical Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:57–66.

- Kobayashi T, Siegmund B, Le Berre C, Wei SC, Ferrante M, Shen B, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6(1):74.

- Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(3):380–389.

- Alatab S, Sepanlou SG, Ikuta K, Vahedi H, Bisignano C, Safiri S, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17–30.

- Lördal M, Burisch J, Langholz E, Knudsen T, Voutilainen M, Moum B, et al. P237 Annual incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease from 2010 to 2017 in four Nordic countries: Results from the TRINordic study. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(Supplement_1):S261–S262.

- Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):720–727.

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46-54.e42.

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769–2778.

- Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, Brinar M, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, et al. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: The ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63(4):588–597.

- Da Silva BC, Lyra AC, Rocha R, Santana GO. Epidemiology, demographic characteristics and prognostic predictors of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(28):9458–9467.

- Zammarchi I, Lanzarotto F, Cannatelli R, Munari F, Benini F, Pozzi A, et al. Elderly-onset vs adult-onset ulcerative colitis: A different natural history? BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):147.

- Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Catinella AP, Hashash JG. A comprehensive review and update on Crohn’s disease. Dis Mon. 2018;64(2):20–57.

- Santos MPC, Gomes C, Torres J. Familial and ethnic risk in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31(1):14–23.

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756–1770.

- Schiff ER, Frampton M, Semplici F, Bloom SL, McCartney SA, Vega R, et al. A New Look at Familial Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish Population. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(11):3049–3057.

- Zhou M, He J, Shen Y, Zhang C, Wang J, Chen Y. New Frontiers in Genetics, Gut Microbiota, and Immunity: A Rosetta Stone for the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. BioMed Res Int. 2017;8201672. doi:10.1155/2017/8201672.

- Alam MT, Amos GCA, Murphy ARJ, Murch S, Wellington EMH, Arasaradnam RP. Microbial imbalance in inflammatory bowel disease patients at different taxonomic levels. Gut Pathog. 2020;12:1.

- Wehkamp J, Götz M, Herrlinger K, Steurer W, Stange EF. Inflammatory bowel disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(5):72–82.

- Moustafa A, Li W, Anderson EL, Wong EHM, Dulai PS, Sandborn WJ, et al. Genetic risk, dysbiosis, and treatment stratification using host genome and gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018;9(1):e132.

- Tripathi MK, Pratap CB, Dixit VK, Singh TB, Shukla SK, Jain AK, et al. Ulcerative colitis and its association with Salmonella species. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2016;5854285.

- Yue B, Luo X, Yu Z, Mani S, Wang Z, Dou W. Inflammatory bowel disease: A potential result from the collusion between gut microbiota and mucosal immune system. Microorganisms. 2019;7(10):440.

- Amarapurkar AD, Amarapurkar DN, Rathi P, Sawant P, Patel N, Kamani P, et al. Risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective multi-center study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37(3):189–195.

- Wang P, Hu J, Ghadermarzi S, Raza A, O’Connell D, Xiao A, et al. Smoking and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comparison of China, India, and the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(10):2703–2713.

- Chen D, Ma J, Ben Q, Lu L, Wan X. Prior Appendectomy and the Onset and Course of Crohn’s Disease in Chinese Patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019. doi:10.1155/2019/8463926.

- Choy MC, Visvanathan K, De Cruz P. An overview of the innate and adaptive immune system in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(1):2–13.

- Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1606–1619.

- Pérez-Jeldres T, Tyler CJ, Boyer JD, Karuppuchamy T, Bamias G, Dulai PS, et al. Cell Trafficking Interference in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Therapeutic Interventions Based on Basic Pathogenesis Concepts. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2019;25(2):270–282.

- Neurath MF. Targeting immune cell circuits and trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(8):970–979.

- Kaur A, Goggolidou P. Ulcerative colitis: Understanding its cellular pathology could provide insights into novel therapies. J Inflamm (London). 2020;17:15.

- Safroneeva E, Vavricka S, Fournier N, Seibold F, Mottet C, Nydegger A, et al. Systematic analysis of factors associated with progression and regression of ulcerative colitis in 918 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(5):540–548.

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott IDR, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(Suppl A):5A-36A.

- Selinger C, Carbonell J, Kane J, Omer M, Ford AC. Treat to target in IBD? Should this be part of an individualised treatment plan? | Frontline Gastroenterology Blog. 2020. https://blogs.bmj.com/fg/2020/02/05/treat-to-target-in-ibd-should-this-be-part-of-an-individualised-treatment-plan/. Accessed 11 January 2021.

- Ungaro R, Colombel JF, Lissoos T, Peyrin-Biroulet L. A Treat-to-Target Update in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):874–883.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant R V., et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1324–1338.

- Drescher H, Lissoos T, Hajisafari E, Evans ER. Treat-to-Target Approach in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Role of Advanced Practice Providers. J Nurse Pract. 2019;15(9):676–681.

- Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D’Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1570–1583.

- Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated Oral 5-Aminosalicylic Acid Therapy for Mildly to Moderately Active Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(26):1625–1629.

- Leung CM, Tang W, Kyaw M, Niamul G, Aniwan S, Limsrivilai J, et al. Endoscopic and histological mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis in the first year of diagnosis: Results from a population-based inception cohort from six countries in Asia. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(12):1440–1448.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L. Mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2020;16(4).

- Solitano V, D’Amico F, Zacharopoulou E, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Early Intervention in Ulcerative Colitis: Ready for Prime Time? J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2646.

- Magro F, Doherty G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Svrcek M, Borralho P, Walsh A, et al. ECCO Position Paper: Harmonization of the Approach to Ulcerative Colitis Histopathology. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(11):1503–1511.

- Torres J, Billioud V, Sachar DB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis as a progressive disease: The forgotten evidence. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(7):1356–1363.

- Colombel JF, Narula N, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Management Strategies to Improve Outcomes of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):351–361.

- Sands BE. The risks and benefits of early immunosuppression and biological therapy. Dig Dis. 2012;30(Suppl 3):100–106.

of interest

are looking at

saved

next event

Developed by EPG Health for Medthority in collaboration with Takeda, with some content provided by Takeda.

C-ANPROM/INT/IBDD/0041 October 2021.